Though cozy with antisemites, this movie star confronted his country’s complicity in the Holocaust

A supremely contradictory figure, Alain Delon, who died at 88, was rightly called a ‘sacred monster’

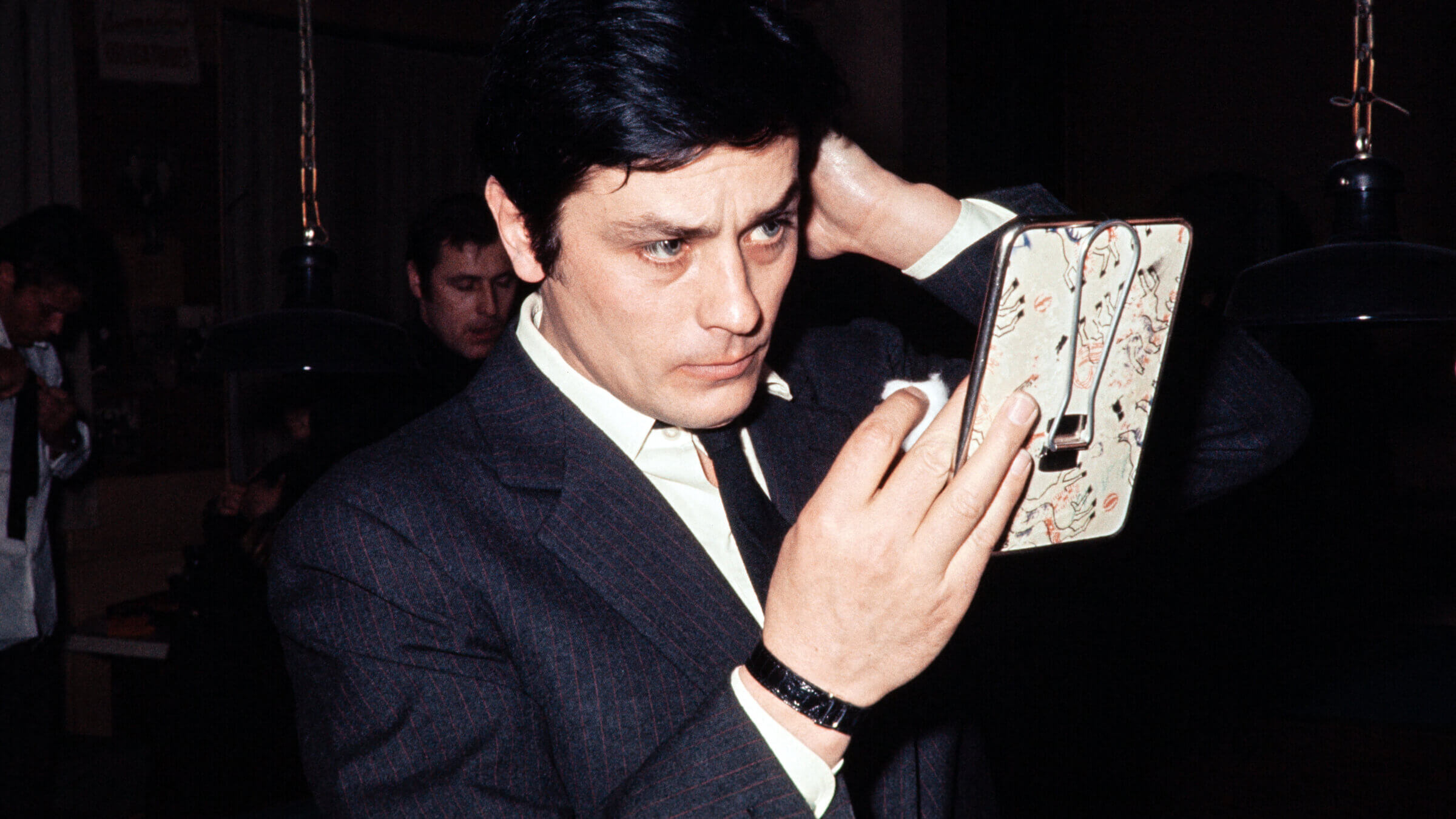

Alain Delon in 1972. Photo by Getty Images

Though Alain Delon was 88 years old and had been in failing health for years, his death on Sunday nevertheless came as a shock. One never expects the death of a monstre sacré — the epithet applied to Delon by countless news outlets — but die he did, not in a hail of police bullets as in The Samourai, but instead in bed at his vast country estate south of Paris.

Monstre sacré. Few public figures better deserved the sobriquet. Delon’s unnerving beauty was monstrous — in the original sense as something prodigious or divine — as was his transfixing screen presence. (This was especially impressive when Delon was silent. The writer François Mauriac remarked, acidly, that Delon “never speaks as well as he does when he stops speaking.”

From the moment he burst into stardom in Purple Noon—the 1959 adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley — through The Samourai and The Leopard to his last screen role in 2008 in Astérix at the Olympics — where he starred as, who else, Julius Caesar — Delon was the most gripping of France’s sacred monsters.

But to qualify as a sacred monster, one must also have a second quality — namely to be both the source and subject of controversies that collapse the wall between your public and private lives. One recent and sordid example is the actor Gérard Depardieu, another monstre sacré who has been hauled into court on multiple accusations of sexual assault, yet also hailed by President Emmanuel Macron as “the pride of France.”

Controversy long hounded Delon. As many obituaries have reminded readers, he indulged in suspect and, at times, sordid behavior. There was, most famously, Delon’s weakness for keeping close company with gangland types who ended up either in prison or the gutter. At times, the lines between his films and his life blurred. For example, the opening day box office receipts for The Sicilian Clan, the crime flick that starred Delon, Jean Gabin, and Lino Ventura, were turbo-charged by the scandal of the murder, never solved, of Stevan Markovic, who had worked as Delon’s bodyguard.

Moreover, in his youth, Delon also ran afoul of the law. While serving with the French Navy in Indochina in the early 1950s, he was arrested for stealing a jeep and promptly driving it into a ditch. A more lasting encounter for Delon than the one with military police was with Jean-Marie Le Pen. The latter was then serving as a parachutist in Indochine, but he arrived too late to see action; the French government under Prime Minister Pierre Mendès-France, in the wake of the humiliating defeat at Dien Bien Phu, was already pulling its troops out of its soon to be former colony. While Delon was eventually discharged, Le Pen did see action a few years later in French Algeria. Some of this action, as the recent book by the historian Fabrice Riceputi on Le Pen and torture makes clear, went beyond the sordid.

But this leads to third quality of a monstre sacré, at least in Delon’s case. Neither the earlier actions nor the later words uttered by Le Pen while the leader of the far-right Front National — words that, barely coded, gave vent to his racist and antisemitic convictions — prevented Delon from becoming and remaining un bon ami. In Paris-Match interview in 1984, Delon explained that he had known Le Pen for many years and believed he was feared because “he is the only politician who is sincere. He says aloud what many people say to themselves.”

In 1987 — the same year Le Pen described the Shoah as a “detail of history” — Delon still refused to denounce his friend. In a widely watched television interview, Delon insisted that he had “points of agreement and disagreement with Jean-Marie Le Pen. He has long been a friend whose company I enjoy. Full stop.”

It thus came as little surprise that among the first political figures to rush to their social platforms and express themselves on Delon’s death was Le Pen’s daughter Marine Le Pen, the current leader of her father’s party (now rebranded the National Rally), who tweeted ‘It is a small part of the France we love that dies with him.” Finishing a close second was Marian Maréchal, the niece of Marine Le Pen who represents yet another extreme-right party, Éric Zemmour’s Reconquête!, who praised the actor’s “icy gaze.” As for the 96-year-old patriarch of the Le Pen clan, his failing health and fading lucidity seems to have preempted a public comment.

Yet, Delon never rallied to Le Pen’s presidential campaigns; a self-described Gaullist, he instead always voted for conservative candidates. More tellingly, Delon was the star and, for the first time in his career, producer of one of his most remarkable films, Monsieur Klein. The film, directed by the expatriate American Joseph Losey and released in 1976, centers on a certain Robert Klein, a heartless art dealer who extorts handsome sums from desperate French Jews who, trying to flee Nazi-occupied Paris, visit his apartment with their prized possessions. For these visitors, the affair is literally existential; for Klein, it is merely transactional. When one customer, shocked by the pittance Klein offers for a family heirloom, blurts “It’s easy for you, when a man is forced to sell,” Klein replies in words as silken as the bathrobe he sports: “But I’m not forced to buy. I’m not a collector. For me, it’s just a job.”

Yet as Klein soon learns, hunting down French and foreign Jews is also just a job for the police of Vichy. When Klein’s identity is confused with another Robert Klein, who happens to be Jewish, he finds himself caught in the remorseless and nearly Kaflkaesque workings of the Vichy bureaucracy. As is the case with Joseph K. in The Trial, Klein’s efforts to clear himself of the crime of being a Jew only reinforce the accusation. Swept up in Vichy’s round-up of Jews in the summer of 1942, Klein is hustled into a cattle car destined for Auschwitz and finds that one of his fellow victims is the customer who had protested the price Klein had offered for his painting.

In 1976, when the film was released, it was more than a job to make the case that the Final Solution in France required the active assistance of French officials. Until 1981, successive French governments had banned Marcel Ophuls’ merciless 1969 documentary on Vichy, The Sorrow and the Pity, while the American historian Robert Paxton’s iconoclastic account of Vichy’s collaboration with Nazi Germany, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, was still largely radioactive in France three years after the publication of the French translation in 1973.

It was only in 1995 that President Jacques Chirac, on the 53rd anniversary of the round-up, publicly affirmed that France, “the homeland of the Enlightenment and of the rights of man, a land of welcome and asylum, on that day committed the irreparable. Breaking its word, it handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners.” As for the victims, Chirac concluded, “we owe them an everlasting debt.”

In effect, Delon makes a similar declaration in his film. In an interview at the time, he acknowledged that the subject of complicity in the Final Solution “frightens everyone.” Nevertheless, he continued, “I knew I had to make the film.” His co-producer Norbert Saada emphasized that Delon was seven years old in 1942. “He knew what was taking place, of the horrors that were committed. None of this was news to him when he first read the scenario. He already knew about it.” Long before many of his fellow French, especially those on the right, did so, Delon proceeded to act on this knowledge.

In an interview with Michel Ciment, Losey hesitated to say how closely Delon identified with the role of Klein, if only because the latter “is hardly a pleasant type, and I cannot say that of Alain.” Nevertheless, Losey added that Klein “is a very complex character, and Alain is as well. Every aspect to his life reflects great and often contradictory complexity.” Perhaps this is what truly makes for a sacré monstre.