A rabbi dates a non-Jew in Netflix’s ‘Nobody Wants This.’ Rabbis in interfaith relationships have thoughts.

‘My own relationship to Judaism has not been in any way deterred,’ said one intermarried rabbi, ‘but rather enhanced’

Kristen Bell and Adam Brody in Netflix’s Nobody Wants This. Photo by Adam Rose/Netflix

Benyamin Cohen is the son of a rabbi who married the daughter of a minister, but that’s a story for another time.

How’s this for the premise of a TV series? Kristen Bell, the spunky Midwestern blond actress, plays a sex podcaster who meets a nice Jewish boy, portrayed with nebbishy charm by Adam Brody, and they end up dating. Oh yeah, I forgot to mention — he’s a rabbi.

The concept may seem like something concocted in a Hollywood laboratory: Take two amiable stars, mix in a romantic comedy, add a dash of Hallmark holiday fun, swirl it together and you’ve got Netflix’s new series, Nobody Wants This. Perhaps the title is a nod to the show’s overbearing Jewish mother, cast to perfection in Tovah Feldshuh, or to how audiences — particularly Jewish ones — may respond. Time will tell.

But while it may seem like the realm of fiction, it certainly is not.

Meet Rabbi Lex Rofeberg, 33, who is married to a non-Jew. “My own relationship to Judaism has not been in any way deterred,” he said, “but rather enhanced, by my relationship to my wife.”

She has forced him, for example, to look at the rhythms and rituals of Jewish life with a fresh perspective. “When a Jewish holiday rolls around for the first time that you’re sharing with somebody, all of a sudden they’re curious. I would’ve just taken the holiday for granted.”

He was ordained in 2021 by Aleph, a rabbinical school affiliated with the Jewish Renewal movement. It never had a policy against intermarried clergy. He had thought he could go to Hebrew Union College, the rabbinical seminary of the Reform movement, the largest denomination of American Judaism. But at the time, the school’s policy was not to ordain rabbis in interfaith relationships.

This summer, the school changed course and now allows such students, following the trend in recent years of other rabbinical seminaries that have updated their policies.

“It’s rare that people I serve have any problem with the fact that I’m in an interfaith relationship,” said the Rhode Island-based Rofeberg, who works for Judaism Unbound, an online Jewish community for the “disaffected but hopeful.”

“The work I do is largely serving the many Jews who are themselves in interfaith relationships. So they don’t give weird looks, because it’s their own story.”

His wife, the granddaughter of an Anglican bishop, ended up adding a bit of Judaism to the marriage. Lex’s last name used to be Rofes which, he said, “doesn’t read Jewish.” His wife was Valerie Langberg. When they married, they blended their names and came up with Rofeberg. “I gained a ‘berg’,” he said with a laugh.

Rofeberg said he’s looking forward to binge-watching the series himself, but is more excited about the “opportunity to engage in deep conversation about clergy relationships,” adding that it “humanizes” rabbis.

“I believe in the power of pop culture,” he said. “I treat new Jewish-themed TV shows or movies in a way similar to if I were around 2,500 years ago and a new book that is now part of the Bible came to exist.”

“If this show is wonderful and does a great job with its romantic representation, that’ll be great. If it’s terrible, it will still create a context for us to wrestle with its approach, just as we do with ancient Jewish sacred texts.”

‘Every marriage is an intermarriage’

Of course, the new Netflix series is not the first piece of pop culture to tackle a rabbi in an interfaith relationship. Perhaps the most famous example is the 2000 romantic comedy Keeping the Faith, starring Ben Stiller as a Manhattan rabbi who dates a non-Jewish blond, played by Jenna Elfman (who, in real life, happens to be a member of the Church of Scientology).

“So much of the discourse on intermarriage is so doom-and-gloom,” said Rabbi Denise Handlarski, the author of The A-Z of Intermarriage and herself married to a non-Jew.

“But to me, really, every marriage is an intermarriage,” said Handlarski, 44. “It’s much easier to be married to somebody who isn’t Jewish but shares a lot of my values, than it would be for me to be married to an Orthodox Jew, where we have completely different lifestyles and beliefs. A Jewish-Jewish marriage is also a kind of intermarriage in many cases.”

She believes that her own marriage has never been an impediment to her work as a member of the clergy. “The opposite is true,” she said. “I think a lot of people are looking for models, considering how many people are marrying or partnered with people who aren’t Jewish. I think it’s exciting for them to see an example of somebody living a committed Jewish life who is intermarried.”

She pointed out that the Jewish community “tried to stop intermarriage” for decades. “If we were going to stop intermarriage, we would have. It’s unstoppable. I think for a lot of people it became a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy: If you intermarry, you’ll leave the Jewish community.”

But she’s seen a change of attitude in recent years. “When communities are welcoming of people who are intermarried and their kids, then they do want to stay engaged Jewishly,” she said, citing data from a Pew Research Center study published in 2021. “I think it’s a question of how welcoming we are and how accessible we make Judaism.”

The evolution of a pop culture intermarriage

The creator of the Netflix series, Erin Foster, drew from her own life. She was a self-described “shiksa” when she met her husband, Simon Tikhman, who is Jewish (but not a rabbi). She ultimately converted and pitched a series based on their relationship. Indeed, it was initially called Shiksa, but was changed after focus groups were unsure what the term meant.

Foster and her husband took the cast to see a performance of Just for Us with comedian Alex Edelman. The award-winning one man show is, among other things, about what it’s like to be Jewish in America today. It also includes a side story about a Jewish boy who has a crush on a non-Jew. Granted, she’s a neo-Nazi. (Spoiler alert: It doesn’t work out.)

Handlarski is quick to point out that Brody starred in The O.C. as Seth Cohen, the son of an intermarried couple. In the series’ finale, he marries his non-Jewish girlfriend in a Jewish ceremony.

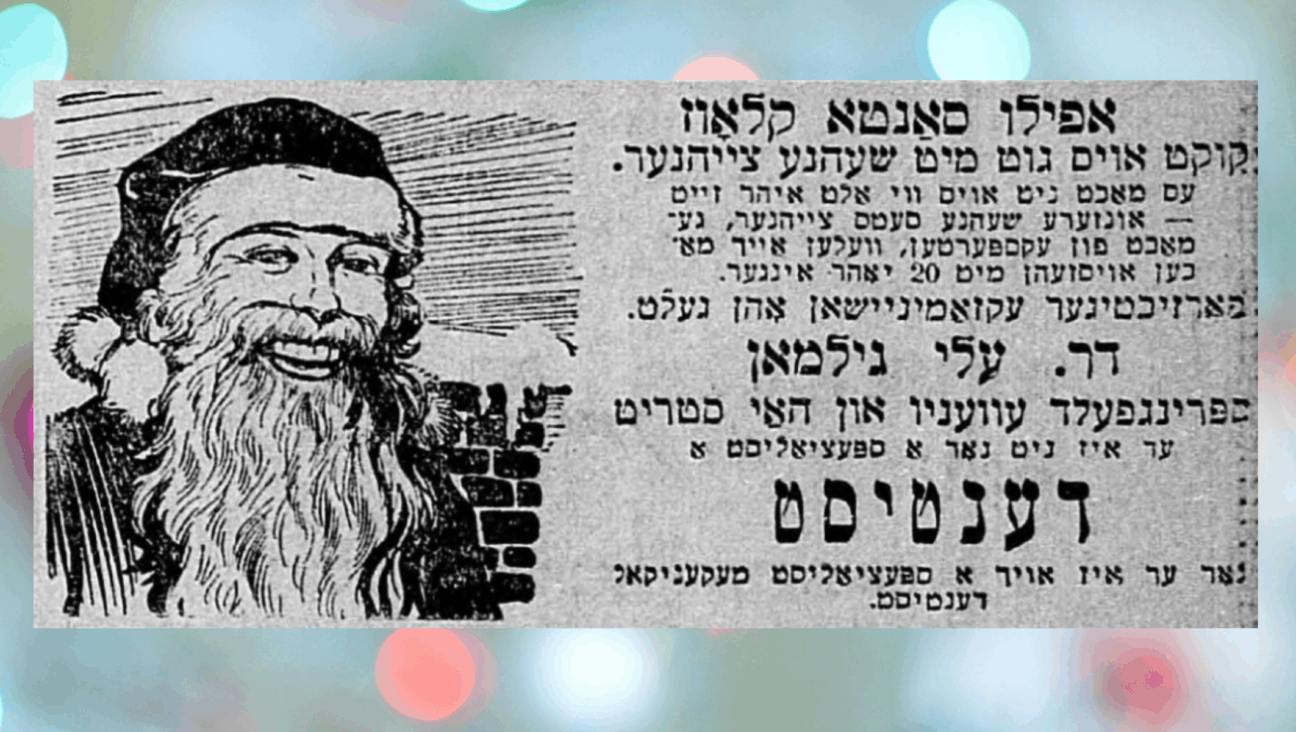

Perhaps that series’ most lasting impact is what it introduced into the American zeitgeist: Chrismukkah, a mashup of winter holidays for interfaith families. (Little known fact: The O.C. writers originally dubbed it “Hanimas.”) Brody’s character called it “the greatest super holiday known to mankind.”

We’ve come a long way from the early 1970s, when CBS aired the short-lived sitcom Bridget Loves Bernie, about a Jewish cab driver married to an Irish Catholic teacher. Despite garnering high ratings, the network canceled the series after one season amid outcries from Jewish groups. Rabbis even organized an advertiser boycott. (Meanwhile, the actors playing the fictional couple ended up having a real-life interfaith wedding and later divorced.)

Fast forward to 2024 when Netflix, the most watched streaming service in the world with more than 270 million users, is releasing — and prominently promoting — a series about a rabbi dating a non-Jew.

Without revealing the ending, Nobody Wants This concludes its 10 episodes on a cliffhanger. Foster, the show’s creator, has teased a possible second season. The potential premise? Kristen Bell’s character converts to Judaism.