A different closet: Queer Zionists navigate the post-Oct. 7 dating scene

Pro-Israel Jews have come to expect hostility on dating apps. It can be even worse in person.

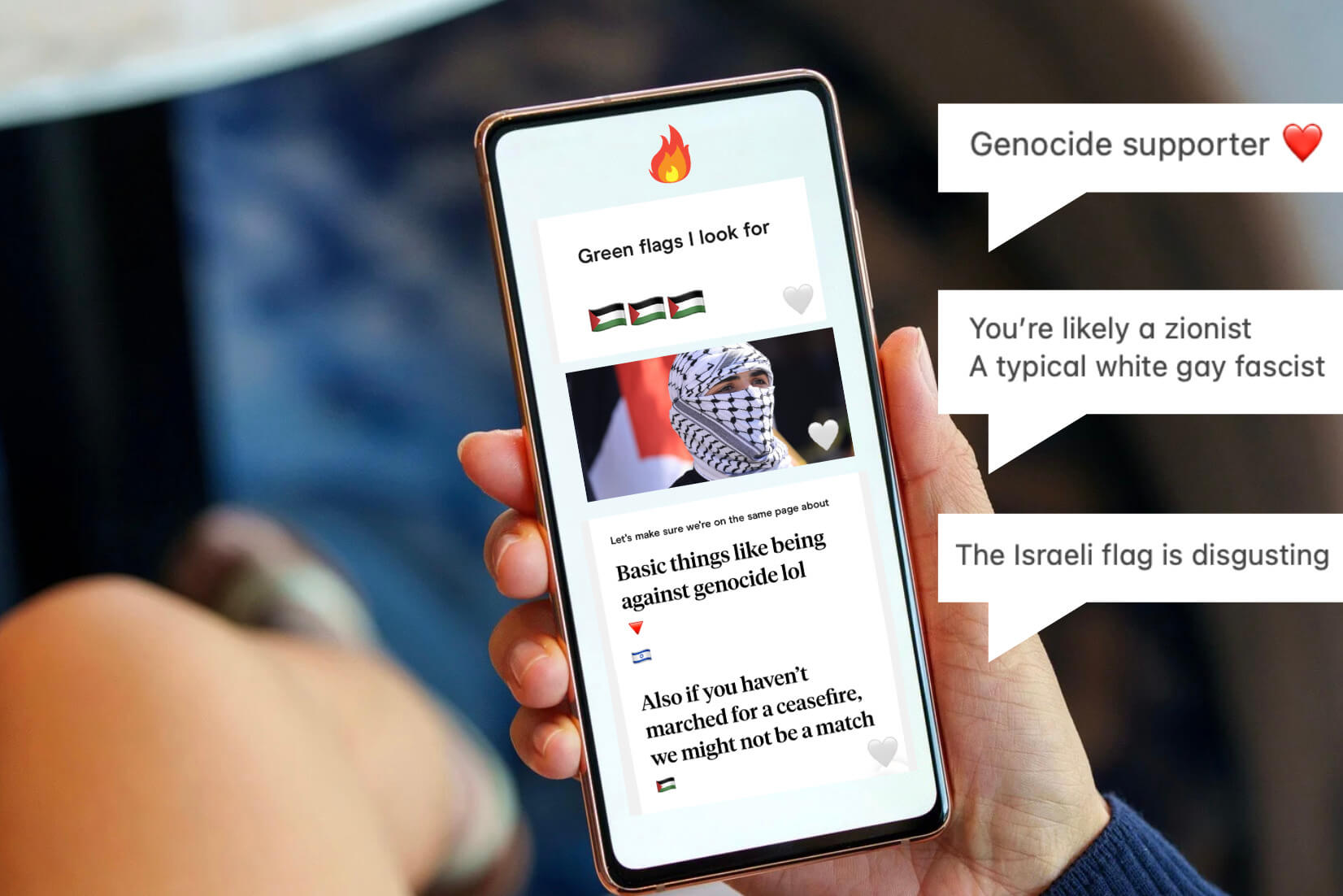

Pro-Israel Jews say the queer dating scene has become a minefield since Oct. 7. Image by Mira Fox

On the gay dating app Grindr, Jason Eisner’s profile contains a Star of David emoji. “It’s impossible to know me and not have my Jewishness come up right away,” Eisner, a theater producer, said by way of explanation. “It’s the biggest part of my identity. It’s what I’m proudest of.”

The Jewish star occasionally attracts a fellow member of the tribe. Lately, though, it has elicited more vitriol than flirtation. Eisner, who is 31 and bicoastal, said he’s had 10 or 15 people start a Grindr chat with him just to interrogate his stance on Israel.

Others just tell, don’t ask.

“No one gives a f— about your religion except you,” one wrote.

“You’re likely a Zionist, a typical whitegay fascist,” said another.

Eisner doesn’t mention Israel anywhere in his profile. But after Oct. 7, he said, any display of Judaism in queer contexts is taken as pro-Israel, a stance that is increasingly unwelcome. When Eisner wears his chai necklace to a gay bar, he expects to be confronted.

Friction between queerness and Zionism has been growing for years. But the uniformity and fervor with which the LBGTQ+ community has rallied against Israel in the past year has left Zionists like Eisner feeling alienated in a new way — that is, the old way: Some compared the experience of being Jewish and pro-Israel in the queer world to being closeted again.

“I’ve felt unmoored,” Eisner said. “I can’t enter these spaces physically anymore without holding my breath or worrying I’m stepping on a landmine. It feels like my world has gotten smaller and smaller and smaller over the last 11 months.”

Israel’s supporters often trumpet the country’s openness towards queer culture, and recognition of same-sex marriages performed elsewhere, in contrast with the hostility toward LGBTQ+ rights among its enemies like Hamas, Hezbollah and Iran. But the international LGBTQ+ community has protested widely and vocally against Israel since Oct. 7, linking the oppression of queer people with the oppression of Palestinians.

Queer solidarity groups were on the front lines of the campus encampment movement. Queer influencers — including Jewish ones — are among the most vocal online voices attacking Israel. “Queers for Palestine” signs are ubiquitous at Pride parades.

The change feels most acute in dating, where every encounter risks backlash or shaming. On the apps, queer Jewish users say anti-Zionism is ubiquitous in bios and personality prompts. Some told of relationships that began before Oct. 7 and foundered over the war. The resulting stress is causing a few to change their outlook on relationships — and rethink their strategy for finding partners.

‘I keep having to narrow down my friends’

The inescapability of Israeli politics in queer dating has caused an identity crisis for Jaz, a 21-year-old legal assistant who spoke on the condition she only be identified by her first name because she is not out to her whole family.

She grew up Hasidic in New York, and said she did not feel like she belonged until she left the Orthodox world and started meeting other queer people.

“I remember it feeling really magical,” she told me. “People were so accepting, and you can be whatever you want to be.”

In spite of her preference to date non-Jews — it helped her leave a religious world she found repressive behind — Jaz was seeing a Jewish woman when Oct. 7 happened. But what she saw as apathy toward Israeli suffering in her partner doomed the relationship. Meanwhile, a queer Jewish women’s chat group Jaz was part of fell apart after some of its members bombarded it with watermelon emojis, which symbolize support for Palestinians.

When she re-entered the dating pool, she discovered the faces that once cherished her background now seemed to shy away from it.

“It felt very hopeless,” she said, “to first deal with, as a teenager and very young adult, like being kicked out and losing religious Jewish community, and then losing queer community, and then losing Jewish queer community.

“I keep having to narrow down my friends,” Jaz continued. “Like, ‘This person I can be fully myself with. This person I can wear a Magen David necklace and I won’t get a slur.’”

She recounted a recent first date, when she couldn’t bring herself to reveal she was Jewish for the first hour. When she finally did, her date didn’t respond. No comments, no follow-up questions. Was her date clocking something and choosing to skip the argument? Did she just not care? It wasn’t clear.

There was no second date.

Lately, Jaz has preferred being in Jewish spaces that aren’t queer-affirming to being in LGBTQ+ spaces, where her Jewishness feels subject to questioning. In the past, she would have chosen a queer house party over a Jewish wedding where she would face uncomfortable questions about her romantic life. Now it’s the other way around.

She’s also changed her settings on the dating app Hinge to only show her Jewish profiles.

“My Jewish identity has become something that’s more important for me to be in touch with,” she said. “Otherwise, I start feeling like I’m lost.”

‘You have to learn how to take care of yourself’

Sam Gordon, who does lighting for a New York theater, also wants to find a Jewish partner, and he relies on the apps because of his work schedule. But it didn’t take him long to see all the Jewish profiles on Hinge. Many belonged to men he already knew or had met.

“The Jewish world is really quite small,” Gordon, 37, said. Eventually he changed his settings.

When the app started showing him non-Jewish profiles, however, Gordon was appalled at the prevalence of Israel-bashing. One person completed the prompt, “Let’s make sure we’re on the same page about…” with: “Basic things like being against genocide lol.” Below it was the inverted red triangle emoji — a symbol used by Hamas militants to mark targets, and by some pro-Palestinian vandals in the U.S. — above an Israeli flag. He reported the account. (Hinge does not inform users whether it takes action on reports.)

Unlike Eisner, Gordon is overt about Zionism in his profile: he mentions volunteering in Israeli agriculture, and some of his answers contain Hebrew. This has not gone unpunished. He showed me a Hinge interaction with a Jewish guy who accepted Gordon’s match only to text: “f— Israel.”

“Maybe those people are looking to put themselves in an echo chamber,” Gordon said, confessing that he has done the same thing, by retreating to Zionist spaces in person and unfollowing anti-Israel accounts on social media. “You have to learn how to take care of yourself,” he explained.

‘It’s so similar to coming out’

The movement of “Queers for Palestine” causes endless frustration for Roniel Tessler, whose parents are Israeli. So Tessler, 38, has been creating pro-Israel content on Instagram since the war started. He runs a WhatsApp group for queer Zionists in New York City, and during the Pride festival in June, its members fanned out across the city with 75 felt pens Tessler bought, blotting out anti-Israel graffiti. Down the road, he hopes to launch a “Queer Zionist Congress.”

Tessler links to his Instagram on his Grindr profile. “Identity politics is not my jam, but today, it’s important,” he explained. “You have to know right now, in the climate that we’re in, what I stand for and what I believe in.”

One user told him: “As a Jew, I’m ashamed that you’re a Jew.” Members of Tessler’s WhatsApp group regularly share such offensive screenshots and commiserate about their dating mishaps.

The steady drip of such spiteful messages, including people calling him a genocide supporter, has Tessler on edge when meeting new people in real life. He worries that a new friend might quickly cut him off upon reviewing his social media.

“It’s so similar to coming out and the fear of being rejected,” Tessler said. “But now it’s being rejected by the people we escaped to, and that’s the heartbreaking part about it.”