Was a ravishing, fictional heroine inspired by a real-life Jewish philanthropist?

Following in the footsteps of Sir Walter Scott, a novelist seeks the inspiration for Rebecca of Ivanhoe

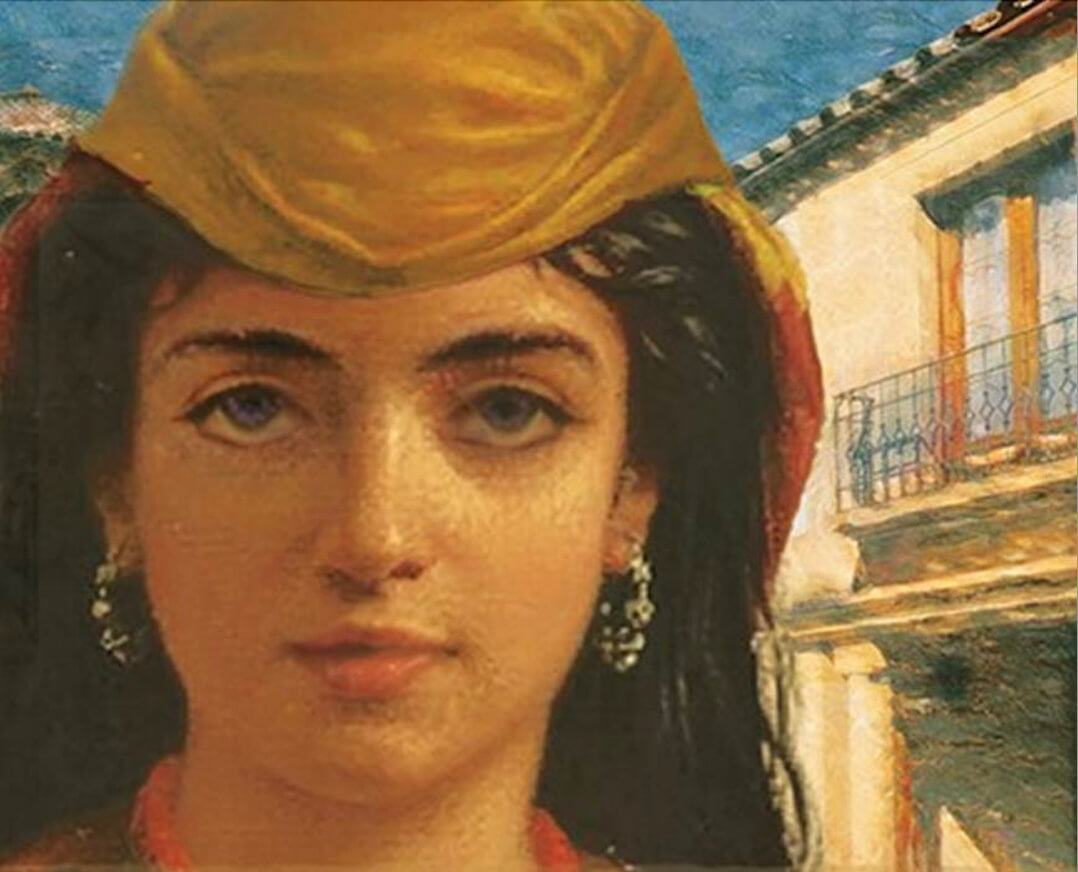

Rebecca of Ivanhoe Courtesy of Alison Bass

When I started writing Rebecca of Ivanhoe, I had no idea where Sir Walter Scott got the inspiration for the character of Rebecca, the beautiful and spirited Jewish healer who is rescued from a hideous death by the knight Ivanhoe. It wasn’t until after I finished my book, which takes up the story of Rebecca after she flees to Spain with her father, that I learned an intriguing tidbit. My sister, who went to Gratz Hebrew school in Philadelphia, told me that Scott had modeled Rebecca on the real-life Jewish educator and philanthropist Rebecca Gratz, who founded Gratz College and a number of other charitable organizations in the early part of the 19th century.

Rebecca Gratz, who, like Sir Walter Scott’s Rebecca, was known to be a great beauty, lived at the same time as Scott. And like the fictional Rebecca, who gave her heart to the Christian knight Ivanhoe but doesn’t marry him in the end, Rebecca Gratz may also have fallen in love with a non-Jew (she writes in one letter of a man whom she loved but could not marry). Historians have speculated that this was Samuel Ewing, a literary lawyer and son of a Presbyterian minister, who no doubt would have required her to convert before they married. Instead, Rebecca Gratz remained single all her life, as Sir Walter Scott suggests his fictional Rebecca will.

Historians also know that Rebecca Gratz had impressed the writer Washington Irving by helping to care for his sickly fiancé. It is also known that, in 1817, Irving visited Sir Walter Scott at his home in Abbotsford, Scotland, and apparently sang Gratz’s praises to the British writer. Two years later, Scott supposedly wrote a note to Irving with a copy of the first edition of Ivanhoe, asking, “How do you like your Rebecca? Does the Rebecca I have pictured compare well with the pattern given?” Although researchers have searched for evidence of this note, according to a scholarly article in the Jewish Women’s Studies journal, no one has found it.

Even so, at the time, many of Rebecca Gratz’s friends believed she was the model for Ivanhoe’s Rebecca, and were constantly asking her about the connection. According to the Jewish Women’s Studies article, Rebecca Gratz even posed for a portrait painted by Thomas Sully in the kind of turban that a medieval Jewish woman might have worn.

Even though the connection has never been verified, historians have said that the character of Rebecca in Ivanhoe was the first favorable depiction of a Jew in British fiction. And it is certainly true that Rebecca Gratz’s life exemplified the independent and courageous spirit that Sir Walter Scott’s Rebecca is known for. In Ivanhoe, for instance, Rebecca climbs out onto a castle parapet and threatens to throw herself off rather than submit to the advances of a lecherous knight. While Rebecca Gratz probably never had to resort to such extreme measures, she herself wrote of the importance of maintaining “an unsubdued spirit.”

Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Philadelphia in 1781, Rebecca Gratz helped to establish the Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances and the Philadelphia Orphan Asylum. She later opened a Hebrew Sunday School, which grew into Gratz College, which still flourishes in Philadelphia today.

In her youth, Rebecca Gratz was also part of a circle of writers, which included Washington Irving and the American author Catherine Sedgwick. While she herself never published anything, her involvement in such lofty literary circles is how she came into contact with Matilda Hoffman, Irving’s beloved fiancé, whom she helped care for before Hoffman’s untimely death.

According to the historical record, Rebecca Gratz also helped her mother care for her father, who had suffered a stroke, and she became the family nurse, caring for one afflicted relative after another. And while she never married, she adored children. When Gratz’s sister Rachel died in 1823, leaving six children, Gratz brought them into her home and raised them.

Gratz, of course, was not known primarily as a healer, the way the character of Rebecca in Ivanhoe is. While Sir Walter Scott goes so far as to depict Rebecca’s healing skills as almost magical, in my novel, I stick to historical reality, portraying Rebecca as making the most of herbs and treatments known to be effective for many ailments in late medieval Europe.

In sum, we will never know for sure whether Rebecca Gratz was the inspiration for Rebecca in Sir Walter Scott’s tale of unrequited love and salvation. But it certainly makes for an interesting story that has endured for more than two centuries, and scholars at Gratz College and elsewhere are still talking about the connection.