In Germany, a Jewish family is reunited with a treasured family object — but also a sense of exile

For Gaby and Sonya Gropman, a trip to Munich represented a homecoming to a land where there is no longer a home

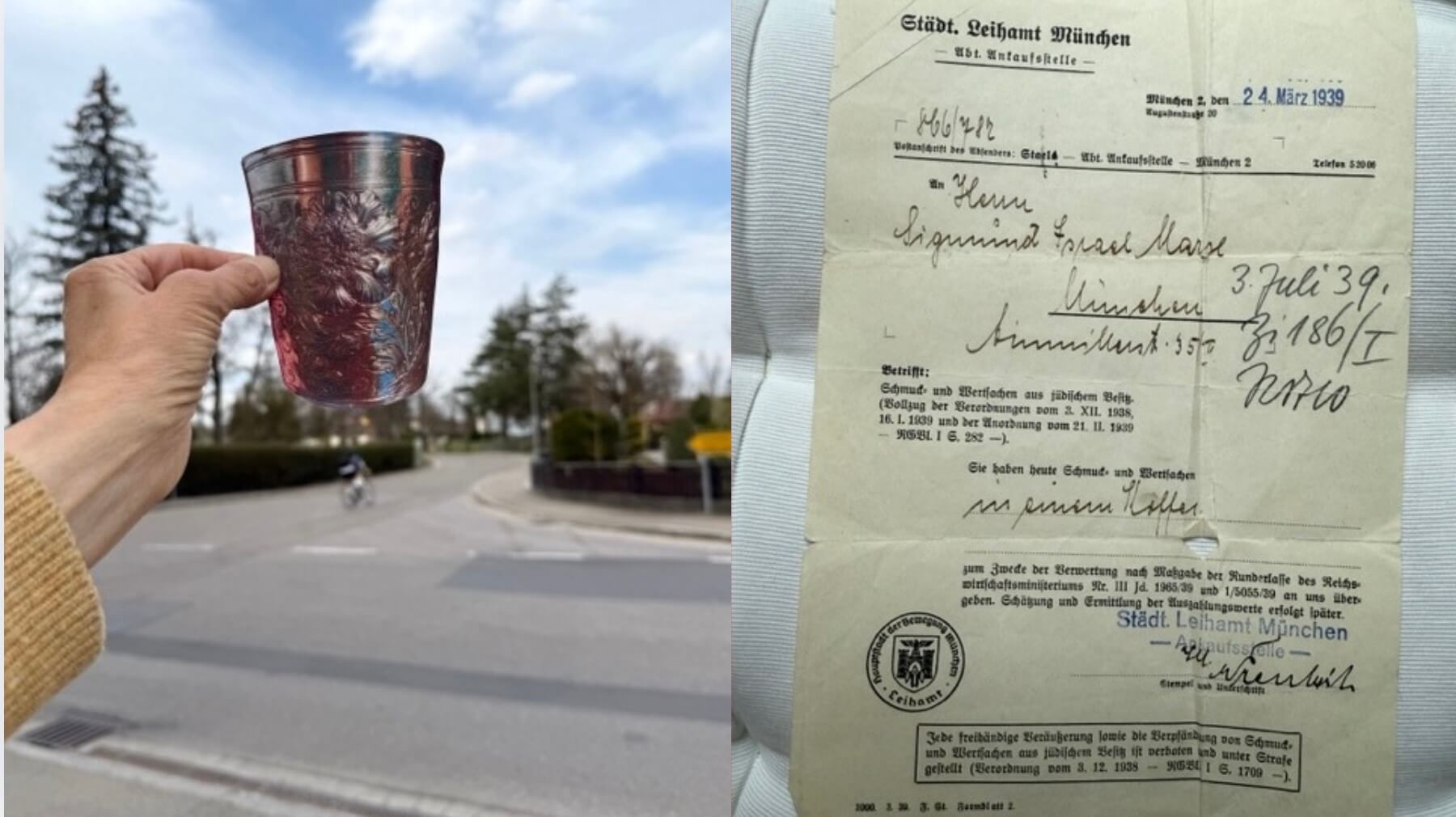

Sigmund Marx brought his silver kiddush cup to a pawn shop in Munich when he had to turn in his silver objects in 1939. His family did not get the cup back until 2025. Courtesy of Gaby and Sonya Gropman

In 2022, an email arrived from Dr. Matthias Weniger, curator at the Bavarian National Museum in Munich, asking Gaby Gropman if she was the granddaughter of Sigmund Marx.

“Yes” was the reply, whereupon Weniger said that he had Sigmund’s silver kiddush cup and would be returning it to our family.

A 17th century cup, it was skillfully decorated with embossed flowers — lifelike daffodils, poppies and tulips with detailed petals and curling leaves. The bottom is stamped with an “N,” indicating that it was made in Nürnberg, a leading city for silver fabrication. For us, the return of Sigmund’s cup – an object we hadn’t even known about previously – was both shocking and moving. In part this was because of its magnificent beauty, but also because it was a tangible remnant of our family that survived and remained on German soil, when nearly all other traces of us have been erased.

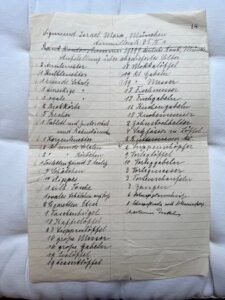

A 1939 law required Jewish families to relinquish their silver (cutlery, candelabras, kiddish cups, and so on) to state-backed pawn shops. Most of it was melted down for the German war effort, some was preserved, and some wound up in museum collections. The Bavarian National Museum in Munich had approximately 120 pieces of “Jewish silver” in their collection and Weniger has spent the past six years researching the provenance of each piece, including tracking down living descendants to personally return the objects to families now living in countries around the world.

After he had returned about 90 pieces, Weniger decided to organize a four-day event to gather the families in Munich. It would include visits to Jewish sites and opportunities to learn more about various related topics.

We decided to attend. We arrived in Munich on Sunday morning, bleary-eyed after the trans-Atlantic flight, but curious about meeting the nearly 80 other attendees. Although we have visited Munich, and Germany, many times, this trip was to be different as we would be among a cohort of German Jews who all had familial roots in Munich.

A connection to a painful past

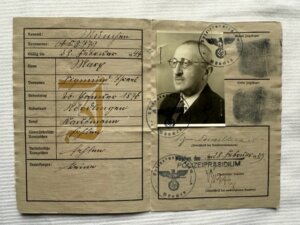

Gaby was born in Bamberg, Germany, in 1938. She and her parents, Erna and Stefan, received a visa and emigrated to the U.S. in 1939. Sigmund and his wife Emma managed to escape Germany in 1939, living in Italy for a year awaiting a visa for the U.S, and then lived with Gaby’s family in New York City for the rest of their lives. They arrived in the U.S. with lift vans, large wooden crates containing nearly all of their household possessions — furniture and kitchenware; clothing; books; photos.

Up until 1939, the Nazis simply wanted Jewish families to leave Germany, while allowing them to flee with their household possessions. This process required paying taxes on one’s own possessions, the result being that we have spent our lives surrounded by objects that our family brought from Germany. We continue to live with and use many of these items, such as black enamelled pots and pans and knives and they are tactile reminders of those who came before us.

But for many other families whose ancestors did not have lift vans, and who have nothing tangible from their ancestors, receiving a returned silver object holds a very different meaning. Jorge Feuchtwanger, one of the other participants we met, said “getting those items [silver objects] back means a lot because they are a connection to a painful past that in my family was not talked about.”

For Germans, living in the aftermath of the unspeakable horror committed by their forefathers, provenance is a weighty issue. Every successful return to the family of an original owner is the perceived righting of a wrong. More than almost any other curator in Germany, Matthias Weniger has succeeded in returning most “Jewish silver” objects in his museum, partly due to his diligence and his personal affinity with Jewish culture, but also because there was a wealth of paper records for him to work with.

This project has attracted much attention in Germany, including from the media and various dignitaries, some of whom spoke on the first day of this event at the Bavarian National Museum. Over the four days, scholars and archivists participated, as did the Duke of Bavaria, who, as an eleven-year-old child, was himself imprisoned at Dachau with his family due to their antifascism. He invited our group to tea at Nymphenburg Castle.

What is expected of us?

Overall, German institutions seem dedicated to giving back to the former Jews of the country. But we must ask: what is expected of us Jews — to be grateful for this “gift” of return? We are reminded of a quote from the Saul Bellow novella, “The Bellarosa Connection”: “First these people murdered you, then they forced you to brood over their crimes.” It was impossible not to think about the reason we were there. And while we met numerous kind, generous Germans on this trip, the fact remains that we were only on this visit because the Holocaust occurred.

It became fatiguing, this dwelling, revisiting, pondering. Because there were two things happening simultaneously – Germans making amends, Jews receiving them. It’s a give and take of the highest order, sin and forgiveness bouncing around like an invisible beach ball. It is of course wonderful to have the silver cup returned to our family, back where it belongs, but it does not change what our family lost. We lost a history that can be traced back at least 500 years; we lost homes, businesses, friendships and, above all, beloved human beings. Matthias understands that. He cannot reverse history. He can only try to reverse a tangible wrong in his care.

The event included a group visit to Dachau, the concentration camp where Stefan, Sigmund, and other male relatives were incarcerated following Kristallnacht, Nov. 9, 1938. No one in our family had ever wanted to visit before, but we decided we should see where our father, grandfather and uncles had been.

Our bus pulled into the parking lot alongside dozens of other buses, all filled with school groups. German kids above the age of 13 are required to visit at least one concentration camp. There was a stark contrast between the groups of teens, huddled in cliques, with phones in the back pockets of their jeans, and our group, many of whom had family members who had been imprisoned here. Some of the buildings, such as the bunkhouses, had been torn down and recreated.

The site in many ways is set up to be educational, with exhibition signage offering explanations and historic photos. We simply wanted to see the place where our relatives had been kept, to see the physical space, feel the earth. In that regard, the visit fell short. One exception was the vast open central space carpeted in white gravel, seemingly intact. That was where prisoners were lined up in formation for roll call, and as Stefan had told us, sometimes were forced to stand for hours in the cold, many developing frostbite and some being shot to death. This was illustrated in a painting made by an inmate, David Ludwig Bloch, that was on display. Though individuals are not recognizable, we realized our relatives were among the many men in the painting. Knowing all this while walking through the site was sobering, and made a lifetime of stories seem real.

The day after the event ended, Gaby was invited to speak at two schools to teenage students about her family history. She spoke in German and fielded a lot of interesting and engaging questions, including many from students who are immigrants themselves. While every school child in Germany learns extensively about the Holocaust, very few have met a Jewish person, and certainly not one who was born in Germany and speaks with a recognizable Bavarian accent, to boot!

A shared sense of exile

The next day we rented a car and drove to two smaller towns where our ancestors resided prior to moving to Munich. Historically, most German Jews were prohibited from living in larger cities. In 1902 when the law changed, the Marx family immediately moved to Munich. Gaby remembers the stories Sigmund told about life in Nördlingen, his native town, a medieval city with an intact wall, 90 miles northwest of Munich.

The small Stadtmuseum currently has an exhibition about Jewish life in Nördlingen, and the director, Andrea Kugler, had been in touch with Gaby a few years ago to get family photos. She graciously showed us around, first meeting us at the Jewish cemetery where two of our ancestors are buried. Because it was Saturday, we couldn’t enter, but the low surrounding wall allowed us to look over (while standing in the driveway of a neighboring house, whose owner warned us not to “stand on his flowers”). Luckily our family gravestones were near the edge, thus visible from outside. It’s a beautiful, neat, rectangle of land with well-kept grass. The stones have Hebrew on one side, German on the other, a 19th century convention.

We then saw the site of the Marx family’s house, which was torn down and rebuilt in recent years, but we got a sense of the location, as it stands directly across from the oldest church and faces what had once been the fruit market. We then visited the museum. To say it was odd to see a family photo of Gaby as a little girl standing next to her grandfather, with the Hudson River in the background, is an understatement.

Six days into our trip, we were somewhat overloaded with nostalgia, history, grief, and revelation. It became exhausting. We stopped by the weekly market and perused the vegetables which lifted our mood. We spotted some of the first white asparagus of the season, marking the beginning of spargelzeit, or asparagus season, practically a national holiday in Germany. Gaby’s father, Stefan, was so enamored of it that he resorted to buying canned white asparagus imported from Germany after WWII, since it was impossible to find it fresh in NYC at that time.

We drove another 30 minutes to Mönchsroth, a smaller town surrounded by agricultural fields, where our family lived prior to Nördlingen. It’s such a tiny place today, that aside from the one or two (closed) restaurant/cafes, we didn’t even see a shop. There was nothing there that called to us, just a small network of residential streets, some driveways with tractors and a church. So we continued on to Shopfloch, a town where Jewish residents of Mönchsroth had buried their dead. We easily found the Jewish cemetery, which dates back to 1612, but again were unable to enter.

No one in our family had ever visited any of these towns, and it felt like discovering an unturned stone. We grasped this countryside of agricultural fields, occasional forests and hills, cities and towns appearing at regular intervals. This gave us a visual reference for where our ancestors lived.

Everything we heard from other attendees confirmed the palpable connection that we all felt to each other through our shared history. We found that the silver objects symbolized a shared origin. What we also shared in this beautiful city of Munich was exile. That is what connected us. As we were driven around in a tour bus, sites were pointed out to us. Our minds became dizzy wandering back and forth from the present to the past, the time when our people occupied these streets.