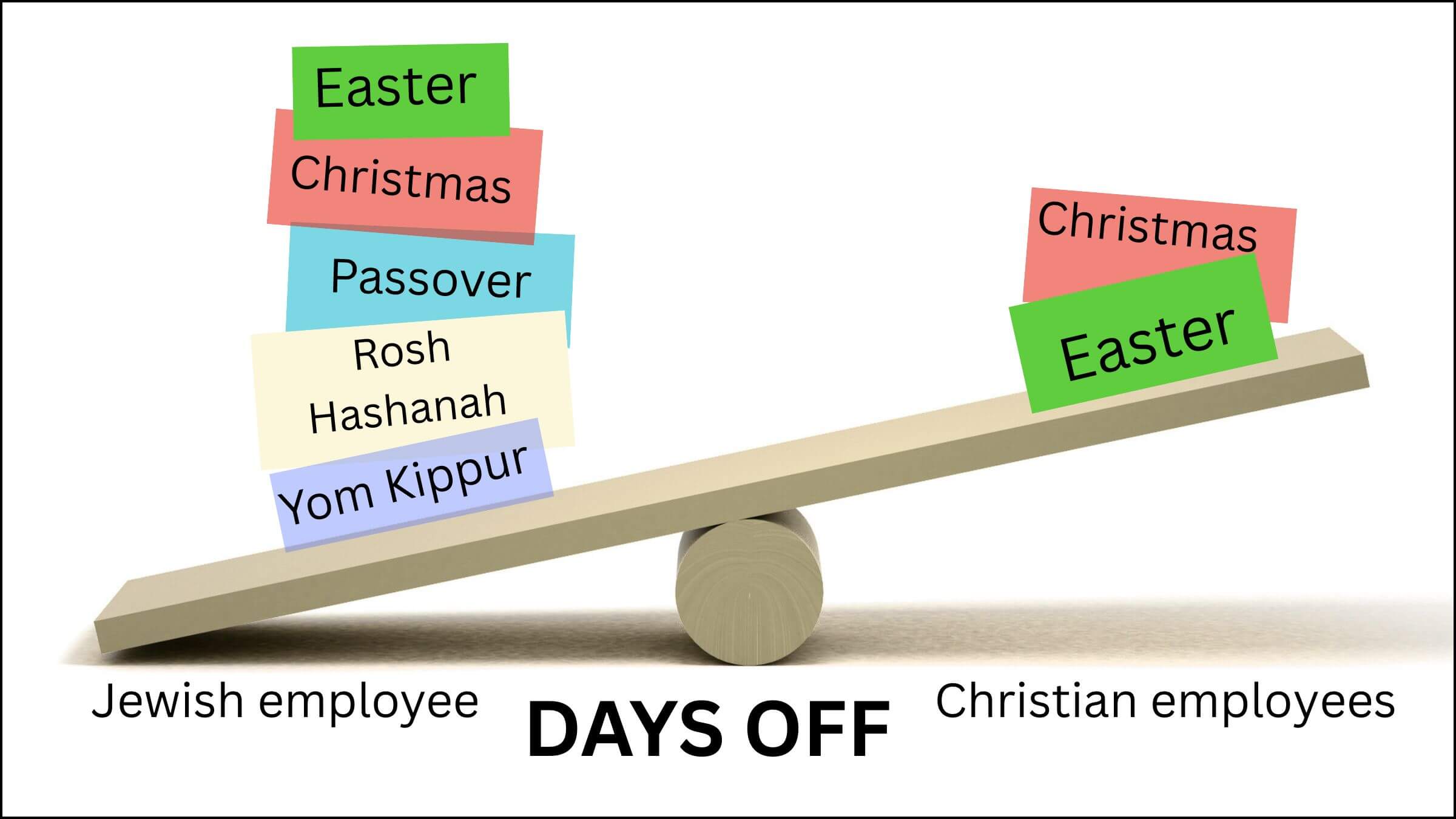

BINTEL BRIEFShould Jewish employees get more days off than everyone else?

Bintel says singling out Jews is a bad idea — even when you’re doing them a favor

Bintel thinks the number of holidays workers are entitled to shouldn’t be based on their religion. Graphic by iStock/Canva

Got problems? Bintel Brief can help! Send your quandaries to [email protected] or submit this form. Anonymity guaranteed.

Bintel disagreed with a recent New York Times Work Friend column in which a boss asked if it was OK to make a Jewish employee work on Christmas and other major Christian holidays. This boss allows the employee — who is the sole Jew on staff — to take off Jewish holidays like Passover and Yom Kippur without using paid time off. The letter-writer said the worker is “double-dipping” by getting both the Jewish and Christian days off. The boss is also tired of having their own holidays interrupted by work emergencies; having the Jewish staffer cover Dec. 25 solves the problem.

In response, the Work Friend columnist said the boss had “the right” to ask their Jewish employee to work on Christian holidays, but that they shouldn’t do so, because that would be singling them out. The columnist also said it was the boss’s job to cover emergencies on holidays.

I agree that the Jewish worker should not be singled out. But the boss is already singling this person out by giving them more days off than everyone else. I can easily imagine other staffers griping about it.

Special treatment isn’t a gift when it sows resentment in the masses. The boss’s own use of the term “double-dipping” hints at the bad vibes this arrangement is already causing.

But there are equitable solutions that are so standard in the workaday world I’m stunned a column on workplace practices failed to mention them.

One is the concept of floating holidays, allowing employees to honor their cultural heritage at their discretion, whether they’re taking off Yom Kippur, Good Friday, Lunar New Year, Juneteenth, Eid al-Fitr or any other day that’s meaningful to them. If folks don’t use floaters for religious or cultural holidays, they can bank them for vacations. Working parents love floaters, too, to cover random days when kids are off from school.

The other standard workplace practice that avoids singling Jews out to work on Christmas or Easter is the concept of incentivizing shifts that are hard to fill, or rotating schedules so the burden is shared. I’ve worked in newsrooms that were open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, but staffing on holidays like Christmas was never a problem because anyone working those days got time-and-a-half pay, or they could bank vacation time off in exchange.

So who ended up working on Christmas? Mostly Jews, but there were also non-Jews who were happy for the extra cash or a future day off. Same thing on Thanksgiving, New Year’s Eve and other holidays where lots of us, for all kinds of reasons, do not take part in a festive gathering.

Conversely, I would never assume that a Jewish worker doesn’t want Christmas off. Many Jews enjoy the day in a secular fashion (Chinese food! movies!). And given our high rates of intermarriage, lots of us celebrate Dec. 25 with non-Jewish family members or friends.

To me, though, the point is this: Everyone in a workplace should have access to the same benefits and opportunities. It’s unfair to give one person more days off than everyone else — even if, at first blush, it seems like the boss is doing their Jewish employee a favor. Really, they’re not. Workplaces are hotbeds of jealousy and allegations of favoritism. You don’t want your colleagues sniping behind your back about Jews getting special treatment from the boss. If floating holidays aren’t enough to cover all the Jewish holidays someone wants, then they’ll have to dip into their vacation time; oh well!

And if a workplace needs coverage on holidays like Christmas, bosses can either incentivize those shifts or institute a schedule where everyone is on call once every few years to work Thanksgiving or Christmas. In other words: Equalize the benefits, equalize the burdens.

My dad always said that when he was in the Army, Jewish soldiers volunteered for Christmas duty as a simple kindness — and, I suspect, to informally sow good will in the ranks. I’ve heard the same thing about hospitals, where many Jewish, Muslim and other non-Christian doctors and nurses make themselves available on Dec. 25 so their colleagues who want the day off can celebrate.

When I worked in newsrooms on Christmas Day, we’d sneak a little menorah in if Hanukkah happened to fall on Dec. 25, and we’d hope that lighting the candles didn’t trigger the office smoke alarm. (It didn’t occur to us to bring in an electric menorah.) We’d also turn an evil trope on its head with this little joke: “Jews do run the media,” we’d say — “but only on Christmas Day.”

What do you think? Send your comments to [email protected] or send in a question of your own. And don’t miss a Bintel: Sign up for our Bintel Brief newsletter.