He escaped the Holocaust and ‘Matzoh Island,’ but America was no promised land

In the graphic memoir ‘The Art of Being a Stranger,’ Karen Bermann tells the story of her father Fritz, who became a maven of maintenance in New York

Author Karen Bermann is an academic architect emerita and self-proclaimed “opportunistic drifter-flaneuse.” Photo by New Jewish Press/University of Toronto Press

The Art of Being a Stranger

By Karen Bermann

New Jewish Press, 248 pages, $27

About halfway through Karen Bermann’s The Art of Being a Stranger, the author’s father Fritz, a Holocaust survivor, asks her, ”Wouldn’t you feel more comfortable if you settled down somewhere?”

“I don’t want to feel more comfortable, Dad,” she replies. “I like being uncomfortable. Uncomfortable is my homeland.”

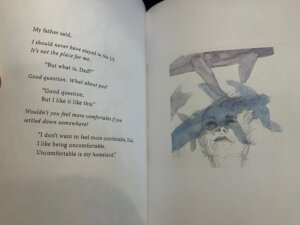

The response ends that section of prose on a page that faces a sketched self-portrait of the author with gray and blue watercolor sharks swimming over her face. It was only at that point, on page 138, I finally began to grasp how this unusual book thinks of itself.

Second-generation survivor stories are relatively common because they are both intense and formative for a generation that has, generally, enjoyed a fortunate enough social and economic position to write about it. The black holes of their parents’ survival, though, tend to be so dense and gravitous that little, if any, of the light of significance escapes the event horizon. So while there are compelling moments and psychologically powerful events, few of the stories that get told at length illuminate an audience beyond their acquaintance group.

This first book from academic architect emerita and self-proclaimed “opportunistic drifter-flaneuse” Bermann, is a notable exception to this tendency. It provides a surprisingly compelling, raw and difficult family autobiography, tracing the history of her irascible refugee father’s journey from Vienna to Palestine to New York. It tells a deliberately incomplete, impressionistic story with a mixture of words and art: it’s a mode of storytelling that, in other hands, could well appear sophomoric.

Bermann explains how her father’s parents ended up married in Vienna as a union of two quite different families. Her source is her father who has a vehement opinion about the comparative worth and religiosity of his mother and father. Josef was born in Galicia, a “semi-literate” son of an “untouchable” who he calls “a boring religious guy, ignorant, rigid.” Melanie was from a more assimilated “but still religious” family in Vienna. She had to marry down to this rural Jew because she was “the runt of the litter / the youngest, and she was deaf in one ear.” Despite that brutal appraisal, Fritz says of his mother that she was “a lively thinking person, / she loved to be with people. / to listen to music, to read, to laugh, and / she didn’t want to have anything to do with my father Josef.”

Fritz was born in Leopoldstadt, Vienna, just as the dark shadow of German Nazism was spreading over Central Europe, forcing him to leave “Mazzesinsel, Matzoh Island, where poor Jews lived.” His mother sent him to Palestine as a 16-year old in 1938 with a leather coat for protection. “Why she gave me a black leather coat to go into the desert, I’ll never know.”

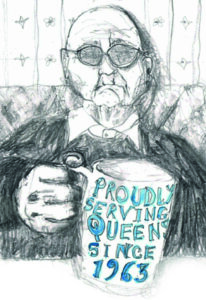

After the first brief section in Vienna the second of the three sections of the book is “Palestine 1938 – 1948.” The majority of the book, however, deals with the time that Fritz spends in New York as a handyman and then as a maven of maintenance. He develops an intimate knowledge of the city and those who are responsible for its welfare. He brings up his family in the borough of Queens but evinces no sentimentality for the city.

”You ask if it was interesting working all those years

in New York building maintenance.

Was it interesting?

My dear child, do you know what I would like?

I’d like to have a giant bulldozer as wide as

the island of Manhattan.

I’d start at Battery Park, and I’d work my way up,

flattening everything in my path….”

The book contains scores of Bermann’s sketches and paintings, and white space surrounds the spare text of the account. That means there are far fewer words than a reader might expect from a 248-page book. The effect is partly poetic without quite being poetry; and with a sense of a confession as Fritz and Karen both unburden themselves. In illustrating her childhood in the shadow of her overbearing father, for example, she asks her mother if it would be possible to have a secret baby that no one would know about. And then she draws that secret baby as well as a secret family that she imagines living between stations in the New York subway.

The great beauty of producing a book that does not conform to a recognized genre is that you have to pay attention to very few rules. The danger and difficulty of having no rules is that it’s hard to know, as an author, whether you have finished making the book and it’s also hard when you limit the guardrails that manage readers’ expectations.

Stranger happily inhabits the “uncomfortable” liminal space between the genres of graphic memoir, survivor testimony, family biography, and poetry; as well as the space between belongings. For a book whose subject matter is so dark, there’s a lightness that comes from some essence of love in the family portraits, especially of her bizarre father, who is an expert at maintaining objects and buildings but, seemingly, terrible at maintaining relationships. The disrepair of family relationships stands in tacit juxtaposition to Fritz’s career in city maintenance. He knows exactly what trapdoors, streets and buildings you can rely on, but his treatment of human interactions is controlling, prejudicial and, in certain cases, violent.

Similarly, his relationship to Judaism is conflicted. We see him proudly identify as Jewish, taking sweet revenge against an antisemite who had employed Fritz thinking that he was a German, but he is deeply distrustful of the religion. One of the two chapters about his life in Vienna is called “Already I knew that God does not exist.” Later, every Yom Kippur, the family leaves Queens to “go to the Palisades in New Jersey.” Fritz goes to avoid synagogue and offending their observant neighbors, but also it was “his High Holy Day too. / Mountains were his ritual and religion.”

Likewise, Fritz knows exactly which family members you can rely on — and it’s usually not the religious ones. In one memorable section, a series of four tulip-inspired watercolors of a glans and prepuce sit under the text of a story where Fritz successfully prevents a religious cousin from checking to see if another cousin’s husband on his deathbed was circumcised.

I thought I would be annoyed by the suggestive and lightly finished art, but I ended up leafing back to see snippets of poetic text and visit pictures that had stuck with me: the heavy charcoal horses fleeing, the glorious abstract Palisades in blue, the frequent portraits of Fritz.

Without spoiling the book, the author has a lot of love and a lot of anger for her father. But sometimes, having someone speak with certitude is reassuring. It’s important to know when your father is being crazy, but paranoids aren’t always wrong.

In a chapter called “Secure in the knowledge that I am a stranger,” Fritz follows a brief musing on why he ever moved to Queens with a short rant against Girl Scouts (“it makes me sick to see a child in uniform”) and then, seemingly unrelated, warns Karen not to protest.

“Don’t you dare go to a demonstration.

We could all get deported.

You don’t think so?

You think being the child of naturalized citizens,

they won’t deport you, too?

Honey, everything the Nazis did was legal.

You are as naive as an American.”