The Borscht Belt was a haven for Jews — and for crossdressers

At Casa Susanna, a resort in the Catskills, guests were able to safely express themselves

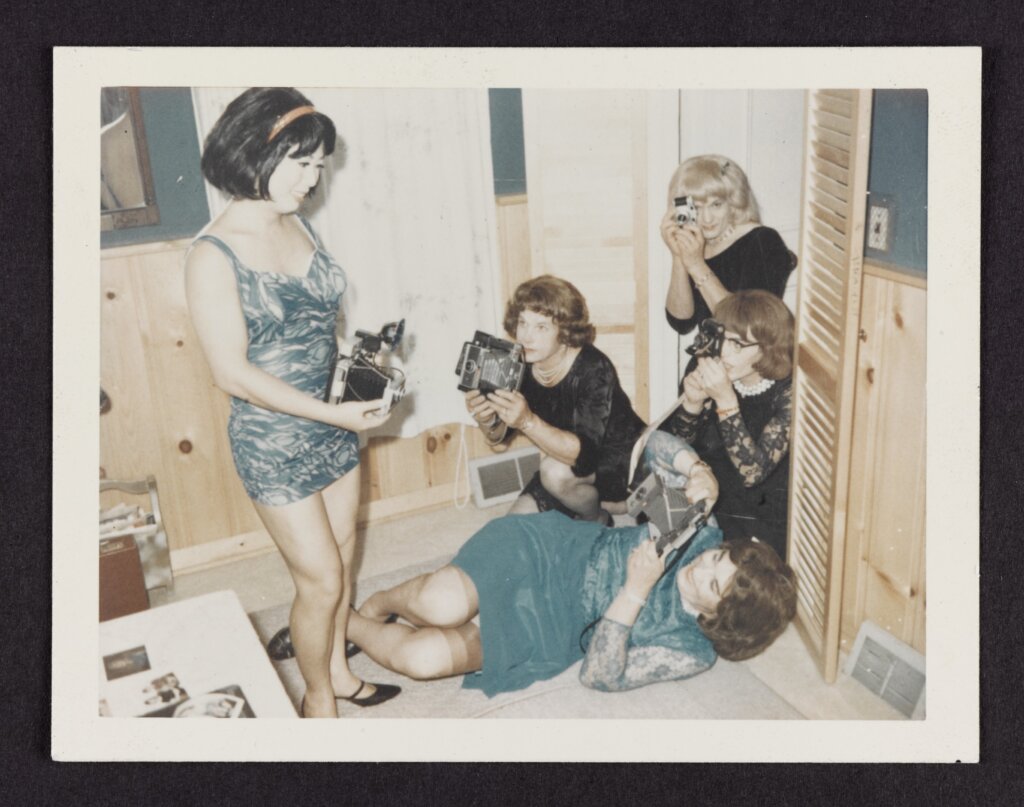

Susanna outside Casa Susanna Photo by Andrea Susan, Photo © AGO/Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum

Though the Borscht Belt is famous as the birthplace of Jewish comedy, it’s less associated with the transgender movement. But the Catskills’ Jewish history is deeply intertwined with its past as one of the first safe places for trans women and crossdressing men to be themselves.

An exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum called “Casa Susanna” explores this latter saga, which took place largely at the eponymous hotel in Jewett, New York. There, Susanna Valenti — a Chilean immigrant born as Humberto Arriagada — and her wife Maria Tornell, an Italian Catholic woman who ran a wig store in Manhattan, hosted a safe space where their community of guests could dress and act as they pleased throughout the 1960s. (The pair also previously ran a short-lived resort called Chevalier d’Eon, after the 18th century French spy who infiltrated the Russian court by dressing as a woman.)

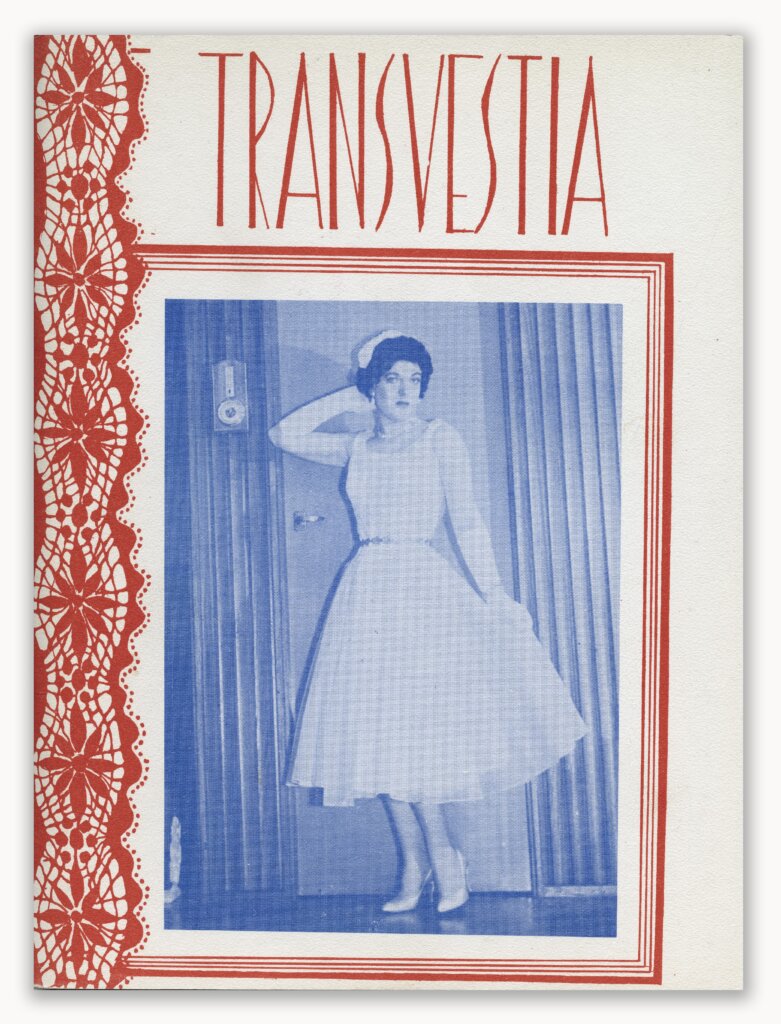

Cross-dressing was taboo at the time, so the community connected largely through exchanging letters and pictures of themselves, as well as via an underground publication called Transvestia, where women published their stories; the exhibit draws heavily from these troves of images of the resort and its activities, which were kept otherwise hidden.

The show offers careful analysis of the importance of Casa Susanna, putting its guests into the historical context of the 1960s — their jobs, their families, the ways they identified within the understandings of sex and gender that dominated that era. Many of the guests considered themselves heterosexual men and were married with families, though some eventually came out as transgender women. Wall text analyzes photos of guests posing while doing chores like sweeping or washing dishes, considering the ways Casa Susanna aspired to a sort of idealized, socially acceptable femininity; Susanna herself even set rules forbidding bathing suits and pants at the resort to reinforce proper, decorous feminine norms — though not everyone hewed to them. The curators even discuss why so many of the photos are Polaroids: Guests wanted to avoid undue scrutiny from photo lab workers, and the new invention of instant film made it possible to keep their photos away from outside eyes.

What the exhibit does not remark on, however, is where Casa Susanna fit in the wider world of Catskills resorts. Because while Casa Susanna may have been the only place devoted to cross-dressing, the area had developed a reputation for being more accepting of outsiders than other popular summer vacation destinations.

The Jewish nature of the Borscht Belt came about in part because many of the other hotels and resorts in posher areas near New York did not allow Jews to stay, posting signs saying “No Hebrews allowed.” So Jews began to open their own vacation spots.

The open-minded nature of these resorts went beyond letting in the Jews that other hotels rejected. The Borscht Belt generally became known for comedy sets that could be bawdier or edgier than was allowed or enjoyed in clubs in the city; another resort, though not aimed at cross-dressers or trans women, offered “female impersonators” as part of dinner entertainment. There was a nudist resort, as well as hotels run by and for Black and Puerto Rican vacationers, who were also not welcomed in many of the more mainstream hotels. Irish, Italian and Polish resort areas dotted the landscape as well.

It’s not that the Borscht Belt was a haven for diversity by today’s standards; these different groups did not necessarily mix and mingle in the same bungalow colonies. Nevertheless, the Catskills’ reputation for acceptance, established by the Jews who built their own iconic resorts, attracted other marginalized groups to the region.

Casa Susanna is not a newly discovered piece of history; many of the photos originally gained public attention after a couple, Michael Hurst and Robert Swope, stumbled upon a cache of them at a flea market in Manhattan, and eventually compiled them into a book. Since then, Harvey Fierstein made a play out of the story, called Casa Valentina; PBS aired a documentary on the resort; and several more books about it came out. The — very Jewish — show Transparent even featured a storyline in which the main character goes on a retreat inspired by Casa Susanna.

But today, in an era in which values of diversity and inclusion are under attack by the government, and trans rights are being curtailed, the images of Casa Susanna feel taboo anew. Even the Met plays its cards close to the chest with the exhibit; the name gives little away about its content to those who are not already familiar with the resort, and it is housed in a small room on the second floor off of the European art wing. Most of my fellow visitors appeared to have stumbled in by chance.

That makes discussing the resort, and the general culture of diversity and acceptance in the Catskills, even more powerful. As I walked into the exhibit, a pair of visitors on their way out were teary. “Oh my god I’m so glad we walked in here” one said. “This was, like, life changing.”

Casa Susanna is on display at the Metropolitan Museum through January 25, 2026.