A new documentary shows what it looks like when Hasidic education fails

New documentary ‘Unorthodox Education’ explores what happens after children leave the yeshiva world

A yeshiva school bus in Brooklyn. Photo by Getty Images

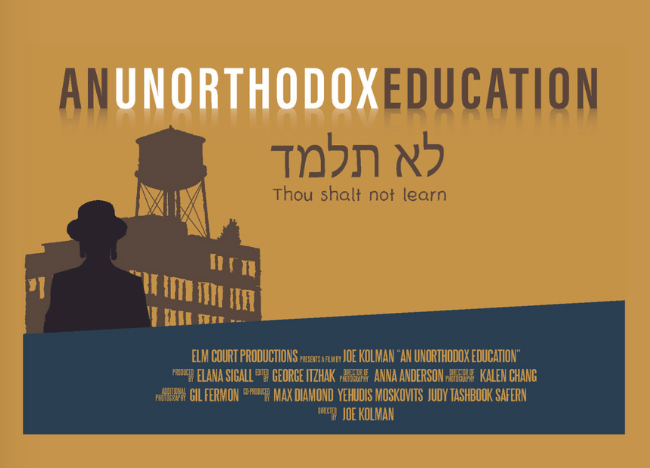

A new documentary on the adequacy of secular education at New York’s yeshivas is debuting just four months after what its director called the “disastrous defeat” of state efforts to exercise oversight on the religious schools, which serve tens of thousands of Haredi children. Unorthodox Education begins a two-week run at Cinema Village in Manhattan on Sep. 19, and the 40-minute film leaves little doubt where it stands on the contentious issue.

“It was outrageous to me that this was going on in America and nobody seemed to know about it,” director Joe Kolman told me.

Kolman initially produced an eight-minute version of the film that he planned to post on YouTube for free, but decided to expand it after showing it to people who were confused after viewing it.

“They didn’t understand why the ultra-Orthodox would deprive their own children of a basic education,” said Kolman.

Kolman’s determination to tackle the issue began during the 2015-2016 academic year when he was introduced to Libby Pollak, a young woman who had left the Hasidic world and was being aided by the organization Footsteps, a nonprofit that has supported more than 2,000 people who have left the insular Orthodox world and helped them acclimate to the mainstream society. Pollak grew up in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, where she attended a high school affiliated with the Belz Hasidim, one of several different Hasidic sects that dominate different neighborhoods in New York City.

“She told me all these horror stories about what she had to go through growing up,” Kolman recalled. “She was desperate to get an education. She had to sneak into the library to get books.”

Pollak earned a B.A. in linguistics and psychology and now works as a professional Yiddish translator, as well as a voice actor for Duolingo’s Yiddish course. She said it was very difficult to leave Hasidic Brooklyn thanks to intense resistance from friends and family. Pollak attributes her success to determination, mazel and being a voracious reader. Before she went to college, Pollak checked the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, out of the library and read the entire book.

In addition to Pollak, we meet other refugees of Haredi life, including Dainy Bernstein, a non-binary graduate of the Bais Yaakov girls schools, who recounted the hurt of participating in the Haredi matchmaking system without being chosen as a bride. Bernstein has since earned a doctorate in English and teaches at Lehman College. We also follow the struggles of Joseph Kraus, who left the Satmar Hasidic community before he turned 18, ending up bouncing around in homeless shelters. He now has more than 3,000 followers on YouTube, where he proclaims, “I grew up in a Hasidic Jewish extreme cult called Kiryas Joel.” (Asked how Kraus is doing these days, Kolman said he hasn’t been in touch with the young man, and Kraus did not respond to my email inquiring about his progress.)

A turning point in the production of the documentary came when Kolman interviewed Elana Sigall, a high school teacher turned lawyer, who has been an expert witness in dozens of court cases where divorcing parents are at loggerheads over their children’s education. Sigall headed New York City’s special education policy before serving as an education adviser to Governor Andrew Cuomo.

“I do a lot of work with people who want their children to leave those schools. And so, I have spent a lot of time in those yeshivas,” Sigall told me. “I don’t think that people understand how extremely undereducated these children are and how enormously deprived they are of access to instruction.”

During the COVID-19 lockdown Kolman asked Sigall to narrate the script for his documentary. After she made corrections, she agreed to serve as the film’s producer.

“Various people from the community or [who] had recently left the community were streaming through my house during COVID, going to my backyard,” she said, referring to the Haredi Jews who were filmed at her home.

Over the course of the five years he worked on Unorthodox Education, Kolman said that he interviewed more than a dozen people who had left the Haredi world. But the director found it extremely challenging to get those who were still part of the close-knit community to appear on camera. A professor at Yeshiva University agreed to be filmed, but afterwards asked Kolman not to use the footage; his request was honored.

A successful Hasidic businessman finally allowed Kolman’s crew to film him in his office after all his employees had left for the day, provided they didn’t show his face. But the Hasid then asked Kolman not to even use the audio from the interview. Kolman agreed, opting to record an actor reading the businessman’s responses.

“They’re getting far less educated today than when I was in school 40 years ago,” the businessman had said in the interview, his back to the camera. For the visuals, Kolman decided to film another actor outside, with his back to the camera.

“It made me realize how difficult it was for people to express their views in this very closed community,” Kolman said of the Hasidic businessman’s reluctance to have his face or voice appear on screen.

Kolman and his team did find footage of prominent Haredi leaders defending the yeshivas.

“The claim that children in the Hasidic schools aren’t receiving a proper education is simply false,” declared New York State Assemblyman Aron Wieder, a yeshiva graduate whose Rockland County district includes the Haredi hamlets of New Square and Monsey. “Our schools are doing just fine, our children are doing just fine and our communities are doing just fine.”

Kolman obtained an audio recording of a 2016 speech in Yiddish by Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum, the leader of the faction of the Satmar Hasidic sect based in the upstate town of Kiryas Joel. In the speech, he admits that students in Satmar schools are intentionally given little secular education so they can be “spending their days fully sacred unto God,” and urges his Hasidim to resist reform efforts.

The defenders of the yeshivas have charged that those who are publicly critical of the religious schools are providing fodder for antisemitism. Many seethed with indignation over a September 2022 New York Times expose that bore the headline “In Hasidic Enclaves, Failing Private Schools Flush With Public Money.” Published in Yiddish as well as English, the yearlong investigation by two Jewish reporters at the Times reported that New York’s yeshivas were unaccountable to outside oversight, despite $1 billion in government funding over a period of four years.

“This film cannot help but enhance antisemitic feelings, feelings that these Jews are backwards, that they’re not interested in helping their kids succeed in life,” Rabbi Yaakov Menken of Baltimore told me; he serves as chief executive officer of the Coalition for Jewish Values, a rabbinic policy organization.

Menken said the filmmakers don’t realize that the study of Talmud, a primary focus of yeshiva education for boys, involves learning law, business, logic, problem solving and economics.

“When, in 3,300 years, has state interference with how Jewish parents educate their children been beneficial?” the rabbi asked, referring to the years since the revelation of the Torah on Mount Sinai. “Government interference in education is not a new thing. The Romans didn’t allow Jews to teach Torah. Government interference has never worked out to be good for the Jews.”

One of the key figures in the decade-long battle for yeshiva reform is Naftuli Moster, the founder of the group YAFFED (Young Advocates for Fair Education), which works to improve secular education in Haredi schools. Moster appears in the film, despite his public turn-around on the issue in June, a stunning disavowal of the organization’s confrontational tactics. In an interview on YouTube with a former member of the Satmar community named Frieda Vizel, Moster called his activist approach misguided. He also expressed regret for his work with Shtetl, a muckraking news site that covered the Haredi community, prompting its board to resign.

In a prepared statement for the Forward, Moster wrote that he respects Kolman’s commitment to the cause of yeshiva reform.

“I no longer believe in the tactics I once employed to seek change in the Haredi education system,” Moster wrote. “I have grown wary of attempts to change a community that is so rooted in tradition and is thriving despite the chaos and dysfunction surrounding us.”

YAFFED accused the New York state legislature last May of jeopardizing the futures of tens of thousands of Jewish children right after it extended, by seven years, the deadline for yeshivas to comply with state standards for secular education. Under the legislative deal, yeshivas will get to pick their own accreditation agencies, the bodies that will judge their own schools. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, no doubt, signed off on the deal with next year’s gubernatorial election in mind; the Hasidic community is known for voting as a bloc, and its support might be pivotal for Hochul’s hopes for reelection in 2026.

Kolman has become well aware that, for elected officials, the issue of adequate secular education in religious schools has become the third rail of municipal politics. During the New York City mayoral primary this spring, he asked the campaign manager of a major candidate whether his boss believed Haredi kids deserve a secular education. In an off-the-record conversation, the campaign manager responded, “Yes, but it’s politically impossible.”

The reluctance to take a stand on an issue that might cost electoral support in the Haredi community extends to the mayoral front-runner Zohran Mamdani, despite his left-leaning politics and criticism of Israel. In a June interview with the Yiddish newspaper Der Blatt, Mamdani pledged to “listen to your leaders” on the issue of education. At a candidates’ forum that same month, Mamdani cast doubt on the viability of enforcing the basic education standards in yeshivas.

“The legislative and executive branches in New York have refused to protect the civil rights of tens of thousands of Jewish kids,” Kolman told me. “We let the leaders of a theocratic religious community dictate educational policy. It’s outrageous.”

Kolman said he’d love for Haredi Jews to see his documentary because it might drive home the sense that there is a problem that needs to be dealt with. But he doesn’t expect many will actually come to a screening, and he doesn’t have much hope that the film will change many minds in the Haredi community.

Still, he’s confident that the story is not quite over.

“I don’t think people are giving up,” said Kolman. “It’s going to take years to resolve this issue.”