Why Jewish Artists Were At the Forefront of Social Awareness

Image by Getty Images

Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art: 1880-1940

by Matthew Baigell

Syracuse University Press, 280 pages, $39.95

This ambitious, meticulous cultural history examines how and why Jewish artists and art critics cared about social upheavals in American life. Focusing on the years of abundant immigration of European Jews to the USA until the eve of U.S. entry into World War II, Baigell, an emeritus professor of art history at Rutgers, has a massive canvas for virtuoso feats of research. These include delving into the ephemera of political cartoons in turn-of-the-century Yiddish newspapers and bringing to light neglected artists as well as overlooked writings by celebrated critics. Baigell points out that recent histories of leftist American art, such as “American Expressionism: Art and Social Change 1920-1970”; “Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926-1956” and “Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in the 1930s” either do not mention, or fail to explain, the high quotient of Jewish artists who shared these concerns. Around forty to fifty percent of the leading artists whose achievements were marked by social awareness were indeed Jewish.

“Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art” does a solid job of redressing this inequity, identifying twin motives for Jewish artists embracing social concerns: Jewish cultural traditions and anti-Semitism. A telling example is the flood of artworks by Jews opposing the lynching of African-Americans. Baigell observes: “Jewish artists made more sculptures, paintings, and especially prints of lynch scenes than of any other subject with the exceptions of boiler-plate anticapitalist, anti-big business, and anti-fat-cat subjects.”

Citing over two dozen instances of this obsession, he reasonably relates it to the case of Leo Frank, the American Jewish factory superintendent lynched in 1915 in Marietta, Georgia. Although the Frank tragedy was doubtless an enduring trauma, not many Jewish artists were inspired to specifically address the subject, as Baigell explains: “It is somewhat surprising that Leo Frank’s lynching prompted so few illustrations in the Jewish press.” He adds that even when one such image appeared in the Jewish press, as in a 1915 issue of “Der Groyser Kundes,” the Yiddish satirical weekly, it indirectly alluded to the subject without showing the lynching. Jewish artists eschewed literal imagery about their own people’s sufferings either from reserve or fear of inciting future atrocities. Did the images of African-Americans serve as an acceptably distanced symbol for Jewish readers of their own travails?

Evidence exists that these artists genuinely cared about the plight of African-Americans, identifying with it to some extent. As Hasia Diner’s “In the Almost Promised Land: American Jews and Blacks, 1915-1935” notes, Jewish publications in Yiddish and English reported on violence against African-Americans as much if not more than periodicals for the general reader did. The socialist realist artist William Gropper (1897–1977), of Romanian-Ukrainian Jewish origin, was aware of this emotional kinship. Gropper told the art administrator August Freundlich in 1968: “I’m from the old school, defending the underdog…. I react, just as Negroes react, because I have felt the same things as a Jew, or my family has.” Identifying with African-Americans was not merely a result of compassion but also a desire to learn from others’ experience. Baigell quotes the Russian-born sculptor Aaron Goodelman (1890-1978): “You cannot grow up without this awareness of who you are. You will not complete yourself as a human being… We have to learn from the Negro people how they fought their way through a terrific struggle and are seeing results. Yes, only through struggle can we reach our goal.”

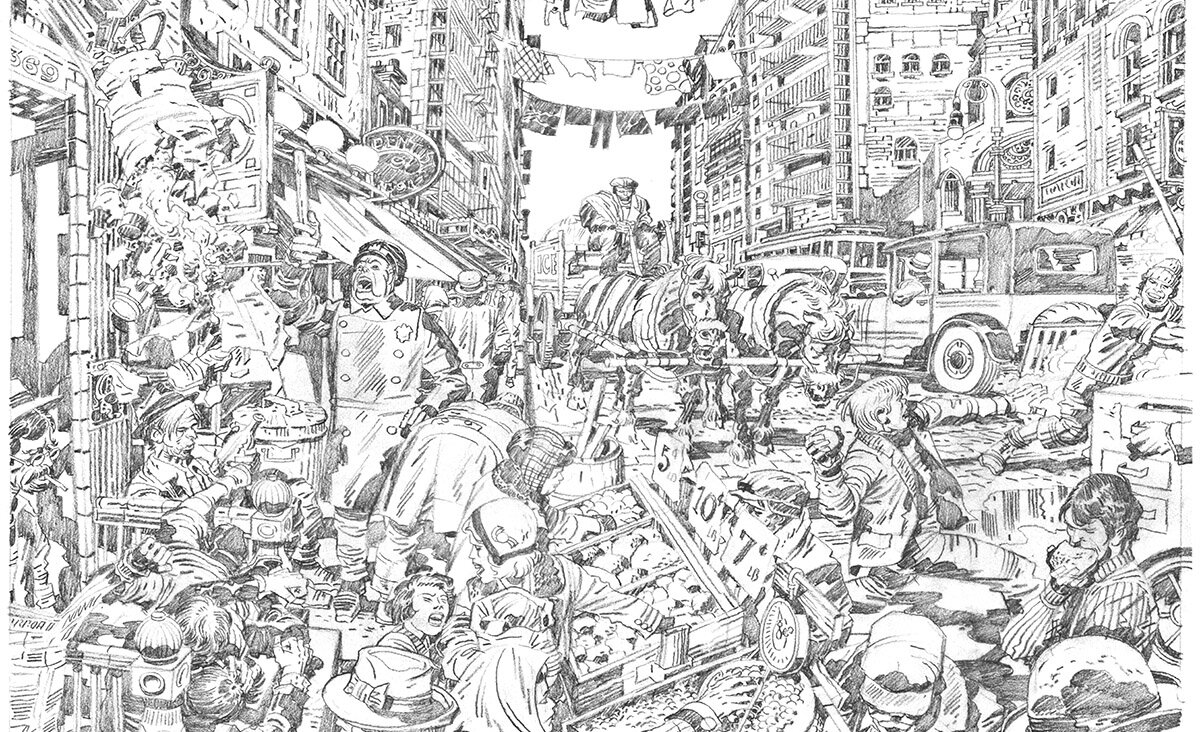

The educational aspect of socially aware Jewish art was evident from the beginnings with such illustrators as the Lithuanian-born Samuel Zagat (1890-1964), a long-time mainstay at the Yiddish Forverts. Zagat’s pet subjects included the exploitation of impoverished Jews by venal landlords. Sometimes didactic, text-heavy cartoons in the Jewish press were intertwined with words until they became tendentious. One such example appeared in 1912 in “Der Groyser Kundes,” showing a downtrodden tailor lighting a menorah, each branch of which is marked with a separate caption: “agitation, organization, strong union, general strike, higher wages, shorter work hours, and better life.” The drawing itself is captioned: “When the tailor lights the menorah, then all will be illuminated. Then there will be more joy and happiness in New York.”

Such bliss was also the goal of fine artists who were exhorted in 1889 by the Forverts’ founding editor Abraham Cahan not to idealize their subjects: “Let your brush emit the heart-rending cries of the downtrodden and the frantic laughter of their reveling oppressors,” wrote Cahan in an editorial. Such empathy was felt to be an essential part of Yiddishkeit. In 1911, the artist and critic Saul Raskin (1878–1966) penned an article comparing images of farm laborers by two 19th century painters, the Frenchman Jean-François Millet and Jozef Israëls, a Dutch Jew. Baigell describes Raskin’s analysis: “Millet was not interested in individuals. Israëls, in contrast, was more sensitive to the particularities of people because he painted their world, their social environment, and their suffering with empathy and pity. Further, Israëls’ subjects were invariably seen in relation to others, not as isolated individuals. Implicit in Raskin’s way of thinking was that Israëls, as a Jew, thought in communitarian terms. This attention to human interactions… probably marked the future of Jewish art.”

Other community-conscious heralds of the future included influential art critics such as Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, and especially Meyer Schapiro (1904–1996). In 1936, Schapiro published an article, “Race, Nationality, and Art,” in which he fiercely denounced anti-Semitic bias among American art critics: “The writers who try to explain modern art as the evil work of the Jews, attack Jewish intellectualism as the cause of abstract art, Jewish emotionalism as the cause of expressionistic art, and Jewish practicality as the cause of realistic art. This ridiculous isolation of the Jews as responsible for modern art is of the same order as the Nazi charge that the Jews as a race are the real pillars of capitalism and also, at the same time, the Bolsheviks who are undermining it.”

Schapiro specifically targeted the influential author Thomas Craven who notoriously wrote in 1934 about the key modernist Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946): “Stieglitz, a Hoboken Jew without knowledge of, or interest in, the historical American background was—quite apart from the doses of purified art he has swallowed—hardly equipped for the leadership of a genuine American expression.”

Schapiro’s bold espousal of the cause of the socially concerned American Jewish artist makes it all the more urgent today for art lovers today to become more aware of this legacy. In 1936, the Philadelphia-born painter Joseph Hirsch (1910-1981) created murals for the Philadelphia Joint Board of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America in 1936, installed in the Sidney Hillman Apartments in his native city. These works, which Baigell lauds as the “least known, but arguably the most complete example of social concern in an art project of the 1930s,” are today “horribly neglected and vandalized.” “Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art” is a timely reminder to heed and preserve this underappreciated past.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.