The Inner Workings of Isaiah Sheffer

Image by Getty Images

Whenever Isaiah Sheffer, the playwright and director who co-founded Symphony Space, worked in his home, he retreated to “The Mineshaft,” a spacious closet located near what was probably a dumb waiter at one point, furnished with a little desk. The makeshift office also accommodated suits, ties and Sheffer’s toolbox. Over the years, boxes of his correspondence, manuscripts, memos and meeting notes also piled up.

Now, much of the paperwork is gone from The Mineshaft, donated by his daughter, Susannah Sheffer, and by his widow, Ethel Sheffer, for a newly-opened archive at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Sorting through Isaiah’s personal history proved to be an emotional and sometimes overwhelming task for the family.

“I became amazed again,” Ethel Sheffer said. “One thinks of the many, many years and all the projects.”

After her husband’s death in 2012, she received an outpouring of emails and support. Nine hundred people showed up to his funeral. Ethel Sheffer believed donating his works to the library would provide not only insight, blueprints and examples for aspiring directors and playwrights, but also a way for her husband to live on.

“People should see his life as an actor and director in New York. It was a checkered career,” she said.

His daughter echoed this sentiment: “People often know one piece and not the whole range.”

Many people recognize Isaiah Sheffer for his work at Symphony Space, a venue he co-founded in 1978 on 96th Street and Broadway on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. The building was used for theater and arts productions, and for Sheffer’s most famed project, “Selected Shorts,” where he brought in celebrities to read short stories for 160 radio stations across the nation. His widow wanted the archive to reiterate that he also produced political cabarets, organized 12-hour music marathons and installed the yearly reading of James Joyce’s “ Ulysses” on June 16.

Mother and daughter spent several months combing through Sheffer’s works and deciding what to keep and what to donate. Every so often, Ethel Sheffer would hear laughter from her daughter, who sat inside the closet. The two came across sonnets Sheffer whimsically wrote for retirements, birthdays and other personal occasions — he sent one to the lawyers arbitrating a case for him — and the correspondence he kept with author, critic and pre-eminent Bertolt Brecht authority Eric Bentley, his neighbor down the hall. Often, when he came home from rehearsals, he would find a humorous note from Bentley tucked under the doorway.

Yet the papers also show the distress and setbacks Sheffer endured. His widow discovered a scribbled note he had written to himself during settlement talks over his off-Broadway musical “The Rise of David Levinsky” —adapted from the novel by legendary Forward editor Ab Cahan— which went to arbitration after the producer wanted to remove Sheffer ’s business partner and Sheffer refused.

“They are trying to take my play from me,” the note read.

“I know he was disappointed and he wanted ‘Levinsky’ to be on Broadway,” Ethel Sheffer said. “It’s kind of a record in his little handwriting.”

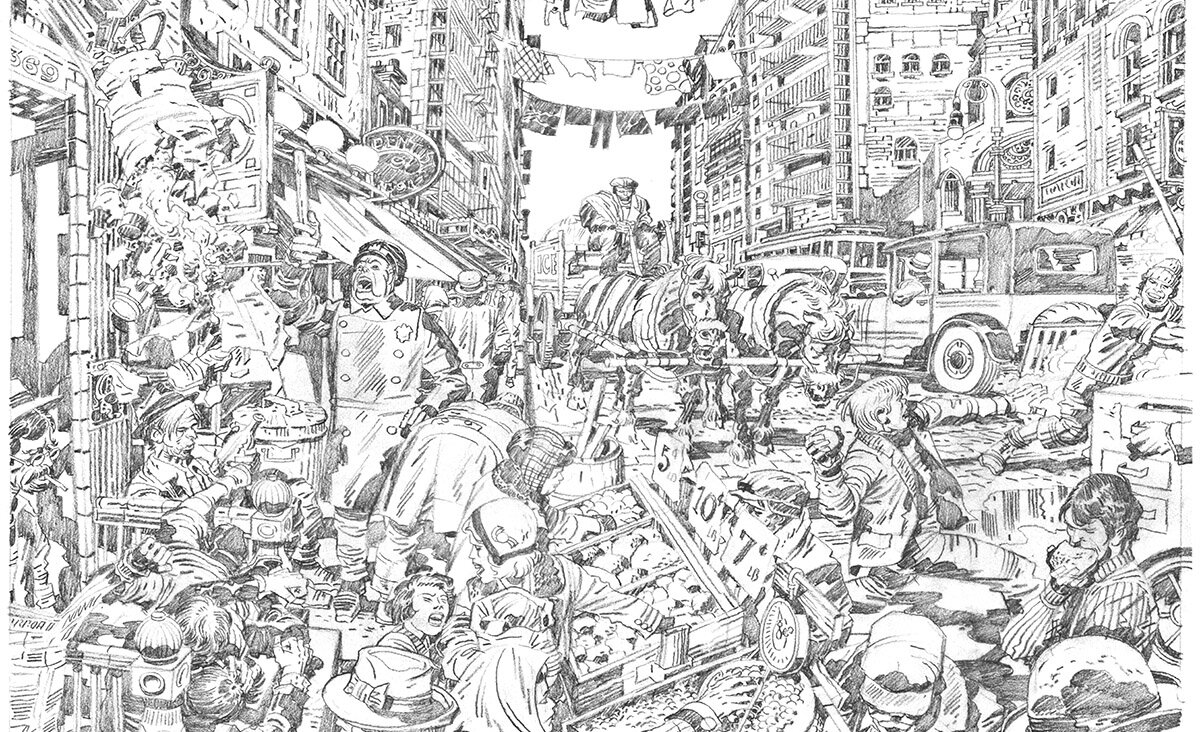

From the Archive: Isaiah Sheffer's archive includes correspondence with his neighbor and business partner Eric Bentley, among other transactions. Image by Britta Lokting

“Isaiah’s collection is particularly diverse,” said Annemarie van Roessel, the library’s assistant curator.

The works have been sorted into four categories: productions, Symphony Space office files, chronological files and personal files. Each could take hours to sift through.

His manuscripts, some of the edges oddly burnt and the paper now yellowing, are slashed with crossed-out words and directions in thick, black pen, like “Check for Paul’s makeup” and “Flip sign off.”

The boxes also contain his personal and business correspondence, which he wrote with haste and urgency, often responding to such setbacks as the rejection of a play with an immediate phone call and a follow-up typed letter. He and Bentley seemed to write on whatever medium was handy: brittle tissue paper, hotel stationery, index cards and postcards.

The letters, even the professional ones, contain a charming humor along with entertaining candor. One particularly long one begins, “excellent reviews. events in order of importance. Variety gave rave. GOOD SOUP NO POOP.”

And even more unusual today with corporate closed-door meetings, the letters provide a glimpse into the inner workings of how people conducted business from decades past. One letter from 1961, addressed to Sheffer from Irving Lewis of the American Federation of Television & Radio Artists, reads, “Your letter reminds me of a kibitzer at a card game, who, after the hand has been played, wants to know why the hand was not played differently.”

“Many things were hard and challenging,” Susannah Sheffer said. She explained that she and her mother wanted the archive to show the trajectory of a play from start to finish, and to allow the public to understand how a production evolves from a simple idea.

But it also reveals much more than that. It shows the chutzpah, charisma and dedication of one man, and how that man not only transformed various plays from start to finish, but also, over time, built an entire legacy.

Britta Lokting is the Forward’s culture fellow.