No Jews Please, We’re British

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

It was, as it should be, dark and damp when I arrived one night in the tiny village of Great Tew, at the northeastern edge of the Cotswolds. A British investment banker I know in New York had recommended eating at the Falkland Arms, a quintessential English pub, he said. And sure enough, there were wooden beams, apple-cheeked barkeeps and a fire in the corner. Everyone knew everyone else— and their dogs— but no one knew me. I ordered an ale and sat at a table, waiting for dinnertime and reading a summer issue of “The New Yorker.”

Eventually, a woman came over and sat down. She’d had a few glasses of wine and was determined to be friendly. Her name was Elspeth, and she and her husband had moved up to the country 18 years earlier. Before that they were in London. But originally she was Irish. Where was I from? New York, I said. No, no, Elspeth clarified, where was my family from? I have dark hair, a beard and a not unprominent nose. Eastern Europe, I said, but generations ago. Isn’t that what’s great about America, Elspeth said, cheerfully: Everyone is from everywhere.

The waitress, Phoebe, brought a menu. Elspeth suggested the ham and eggs with toast. Unless, she said: Are you Jewish at all? I am Jewish, I told her, but not at all kosher. Oh, how wonderful, she said. She just loves the Jewish people. There’s a real community at the pub, she said; isn’t that very Jewish? And of course, sometimes her husband, Richard, tells her not to be so Jewish, she said with a laugh; but what’s wrong if she chooses to answer a question with a question? Eventually, Elspeth and I settled on a shrimp appetizer and bangers and mash — she’d lost interest in the laws of kashrut, or perhaps just didn’t know most of them — then she went outside for a smoke. Richard popped over for a chat, too, reminiscing about his visits to New York. My food came and I ate it; I finished my pint, said goodbye and headed to the door.

As I walked out, I heard Richard talking to the group: Oh, Elspeth, he chided, stop being so Jewish!

•

The Menier Chocolate Factory, in London, is a tiny theater that stages big Broadway musicals. Its current production — which sold out its run in something like an hour and half — is “Funny Girl.” A West End transfer has been announced. Two nights after my dinner in Great Tew, I took a seat on the center aisle.

“Funny Girl,” of course, is the musical that made Barbra Streisand, first on Broadway and then with the 1968 movie, Barbra Streisand. It’s a specifically Jewish tale — Fanny Brice, a poor Brooklyn Jewish girl, finds fame and fortune through chutzpah and vaudeville — that’s indelibly associated with an iconically Jewish performer. The musical, traditionally, reeks of Yiddishkeit, from its heroine to its milieu to its characters’ names to their mannerisms. The Brits love the Jewish people.

But do they?

The Menier is a fabulous place to see a show. There’s no New York equivalent, really — it’s an infinitesimal 150-seat theater, with a small and squat stage, where you can watch lush musicals performed from about 15 feet away. The closest analogue I can think of is when the Classic Stage Company, in the East Village, performed Sondheim’s “Passion,” with the orchestra nestled overhead — although even that space isn’t nearly so richly claustrophobic.

“Funny Girl” has a fantastic, memorable score, with music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Bob Merrill. It includes several songs forever associated with Streisand — especially “People” and “Don’t Rain on My Parade” — and several more that are less well known but similarly unforgettable. It has a less successful book, by Isobel Lennart, that has been revised here, still not quite successfully, by Harvey Fierstein. Michael Mayer directed, and his designer, Michael Pavelka, created a perfect set, a sort of bizarre, off-kilter grand vaudeville house, on which everything transpires.

But you are here to see the leading lady, Sheridan Smith. Smith has two Olivier Awards, London’s equivalent to the Tonys, but no New York credits. She is spectacular, with comic timing that makes you double over and a voice that knocks you down. Her Nicky Arnstein, played by Darius Campbell, is less successful, handsome and charmless. Her Fanny Brice is also the anti-Streisand, very compellingly so. Brice was a poor girl, convinced she was unattractive, unlovable, that only her shtick made her popular. Where Streisand was never less than regal, Smith makes you feel her character’s vulnerability. At the end of the first act, Fanny realizes she must chase after the one man she’s loved, the one man who’s made her feel beautiful; in the movie, Streisand famously commandeers a tugboat to do so. It’s the “Don’t Rain on My Parade” moment, and, for Smith, it isn’t just a beautiful song; it’s a beautiful, yearning moment. Where Streisand was simply determined, Smith is also, in a way, desperate.

What Smith is not, however, is Jewish. The entire show is rendered in an English approximation of Brooklynese; most explicit Jewishness has been removed. Smith, tiny and round-faced, with pale skin and a pixie nose, looks, if anything, Irish. (That Mama Brice runs a saloon in Brooklyn and pals around with a woman named Mrs. Meeker only underlines that feeling.)

It’s a “Funny Girl” that may think Yiddish, but dresses British.

•

The next night I was in the fifth row of the Savoy Theatre, a subterranean Art Deco palace just off the Strand in the West End, for the opening night of “Guys and Dolls.” I have to disqualify myself from reviewing this production: Its American director, Gordon Greenberg, is a friend, and I was there as his guest. But I can report that, in The Times, Ann Treneman said that “it is bursting with that most American of words — pizzazz” and that Michael Billington, in the Guardian, pronounced, “A classic musical has been delivered with grace and elan.”

“Guys and Dolls” is one of the truly great American musicals, and its 1992 Broadway revival, directed by Jerry Zaks and starring Nathan Lane and Peter Gallagher, is a legendary production that also stands as a signal memory in my development as a theatergoer. It’s a show that’s nearly impossible to mess up, although the British director Des McAnuff managed to do so with an over-directed, over-designed, under-performed 2009 Broadway outing that ran for only three months.

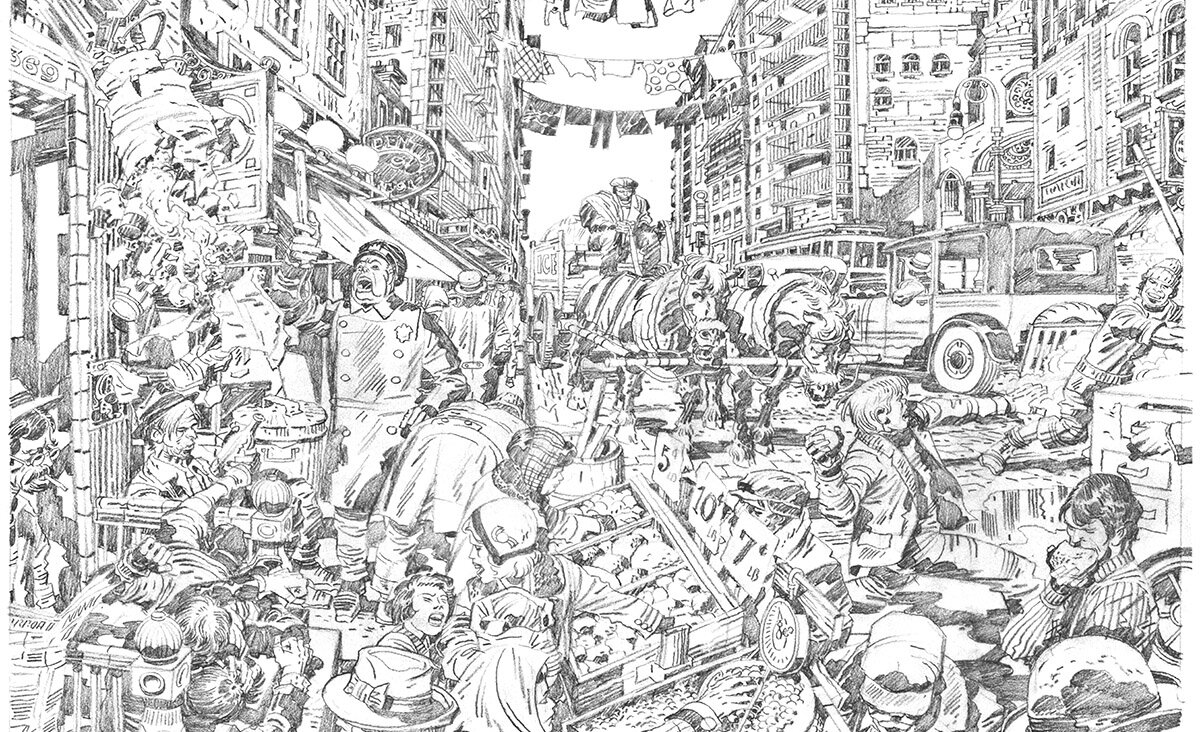

Based on the Times Square stories of Damon Runyon, the musical’s beauty is found in its near-perfect songs, with music and lyrics by Frank Loesser. Although he was born a high-culture German Jew, Loesser, as Benjamin Ivry wrote in this paper in 2009, adopted a Lower East Side affect and accent as he made his way through Tin Pan Alley. When long-engaged but still unmarried lovebirds Nathan Detroit, the gambler, and Miss Adelaide, his showgirl girlfriend, fight, Loesser gave us the song “So Sue Me” — a more Jewish title could you imagine? — and in it a deliciously Jewishish couplet: “A right, already; I’m just a no-goodnik/ A right, already; it’s true. So, nu?” (I’ve seen that final lyric rendered as “So new?” — but we all know what it should be.)

But Loesser and his book writers, Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows, never make their characters explicitly Jewish. They’re a bunch of Broadway ne’er-do-wells, speaking in an inauthentic but wonderfully stylized New Yorkese, with no discernable ethnic identity, other than that they are ethnic. (Though their last names are not: Detroit, Masterson, Johnson.) That the accents are always off-kilter makes their British versions, in this production, entirely convincing; and that the characters are never actually Jewish means that their Jewish souls, even in Covent Garden, can shine through.

Treneman, in The Times, called the production “American”; I don’t think she realized it, but she meant that it had a sense of place, a New Yorkiness, that it’s still very Jewish.

The Brits love the Jewish people, and even more so when they don’t know they do.

•

I met a guy for drinks the next evening. We ended up going for dinner, too, and had a nice, long conversation. He was a native Londoner; he now works as a lawyer in Fitzrovia and lives in what he termed “bourgeois splendor” near Hampstead Heath. He travels a lot, as you can with Britain’s cheap holidaymaker airfares, and goes to Israel a few times a year. His last name is Lee.

Actually, he told me, that’s what it is now. It used to be Levy. His father changed it, in the 1960s. He felt he had to.

Jesse Oxfeld has written about theater for Entertainment Weekly, New York Magazine and the New York Observer.