In Chicago, All Roads Led to Lois Weisberg

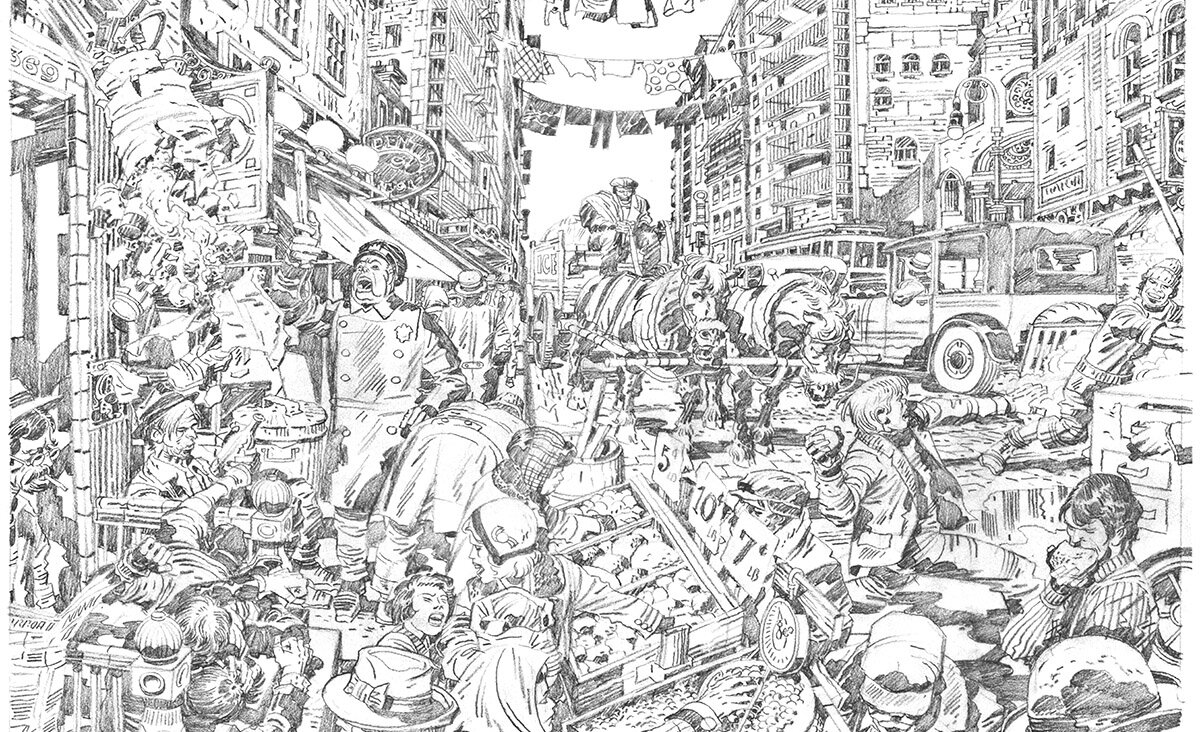

Image by Anya Ulinich

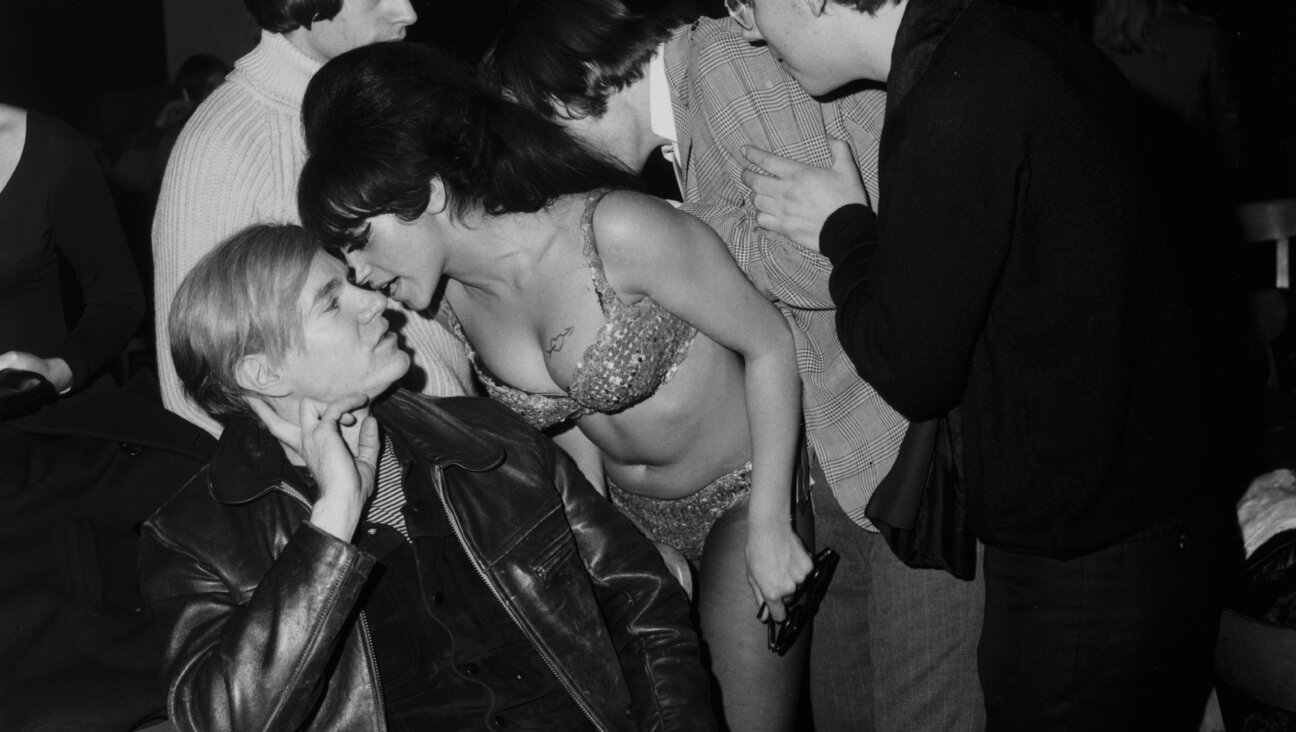

A New Yorker profile written by Malcolm Gladwell in 1999 made Lois Weisberg, Chicago’s commissioner of cultural affairs, famous because, Gladwell wrote, she was among those “who make the world work.” Weisberg appeared in Gladwell’s best-selling book “The Tipping Point,” largely because of her facility with viral networking and her dedication to all kinds of causes throughout Chicago. Anyone who worked with her, as I did, regarded her as an implacable force.

Weisberg lived vigorously until the age of 90, before finally passing at her home in Palmetto Bay, Florida, on January 13. Hers was not an uncommon story of success, but her unique combination of energy, creativity and determination enlarged in scope and influence nearly everything she came upon — despite the fact that she was barely taller than 5 feet and usually appeared within a cloud of cigarette smoke. In addition to her work in arts and culture, she made lasting contributions to preserving and protecting Chicago parks and the metropolitan environment, as well as to integrating public housing into safe neighborhoods.

Before I worked with her at the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs I was told to avoid her. I was a press secretary for the Chicago corporation counsel, Judson Miner, at the city’s Law Department during the terms of Harold Washington, Chicago’s first African-American mayor. To the police security around the mayor’s office Weisberg was known as Yoda, but no one could stop her from going to see him the mayor when she wanted to. She was also The Force.

Never meet with her or her staff, we were told. “Whenever Yoda comes down here,” one deputy corporation counsel said, “we wind up going to court.” Weisberg abided by the law for the most part, but sometimes she overlooked its inconveniences if they seemed to prevent her from realizing her ideas as the city’s director of special events. When our receptionist saw her coming, she would alert several attorneys, who ran into washrooms or anywhere else they could hide.

Weisberg was a yenta in the best sense of the term, part of Chicago’s predominately Jewish “Lakefront liberals.” Her department’s staff appeared to be ex parte, making purchases for services or equipment or whatever by their own terms, sometimes not paying complete attention to the obligations the process required. Her job was to create spectacle. So if it was not quite clear that creating a gospel music festival and hosting it on public land might violate laws on public display of religion, well, let them sue.

Weisberg’s service as an American civic cultural impresario is sui generis; she differs from New York’s Henry Geldzahler — the art curator and critic and cultural affairs director from 1977 to 1982 for New York City’s mayor, Ed Koch — in that she worked the neighborhoods as much, perhaps even more, than she did giant downtown events. Whereas Geldzahler was deeply trained in art history and was a significant presence on New York’s contemporary visual art scene for more than 30 years, Weisberg worked from communities into institutions. She was a kid from the West Side of Chicago who grew up in the Austin neighborhood, primarily middle-class with a substantial Jewish population. She knew not only the neighborhoods, but also the people in them who made things happen. So when she developed performance programs or art exhibits in all kinds of spaces, she championed local artists.

Weisberg took over Chicago’s Cultural Affairs Department at a critical time. Washington died in 1987, after which Eugene Sawyer served as mayor until Richard M. Daley, son of “Boss” Daley, was elected in 1989. The cultural affairs commissioner at the time, Joan Harris, was (and still is) a prominent local and national arts advocate (she recently received a National Medal of Arts from President Obama). Harris was fired, very publicly and ironically, by Daley (whom she and her philanthropic husband, the late Irving Harris, supported). She came under fire for rebuking Daley’s initiative to sell the former central Chicago Public Library building to the Museum of Contemporary Art, which declined.

Harris was deep into planning to transform the building into the Chicago Cultural Center; Daley certainly knew this, but disregarded it. After firing Harris in one of his many public fits of pique, he needed Weisberg far more than she needed the job. I observed the situation as an assistant commissioner of cultural affairs and would later be fired for, according to Weisberg, no other reason than having worked with Mrs. Harris.

Weisberg served as commissioner for more than two decades (she was the only commissioner to last just about as long as Daley). During her reign, she gave Chicago its greatest international tourism draws, such as the wildly popular art exhibit “Cows on Parade” (an idea she borrowed from seeing an exhibit of lions on the streets of Zurich that engaged local artists, designers and others to paint and decorate fiberglass cow statues).

But when Daley proposed folding Weisberg’s former department, Special Events, into Cultural Affairs in January 2011, Weisberg disagreed, exited, and was not shy about expressing her disappointment with Daley.

Many obituaries of Weisberg have noted her connections to famous people from many realms and how she could find the common interest among them to further her work. But perhaps more important were the many people who worked for her and with her and learned the value of bringing together folks with various interests to work toward the public good on important issues. The organizations Weisberg either founded or guided, such as Friends of the Parks, and Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, are still operating today. She was Facebook before it existed.

Lois Weisberg’s contributions to Chicago place her among the city’s most marvelous characters, and evince an honest fidelity to the idea that arts and culture are crucial to a city’s infrastructure, as important to a city as streets and bridges.

Ronald Litke is a Chicago-based journalist.