Houdini’s Astounding Jewish History Revealed!

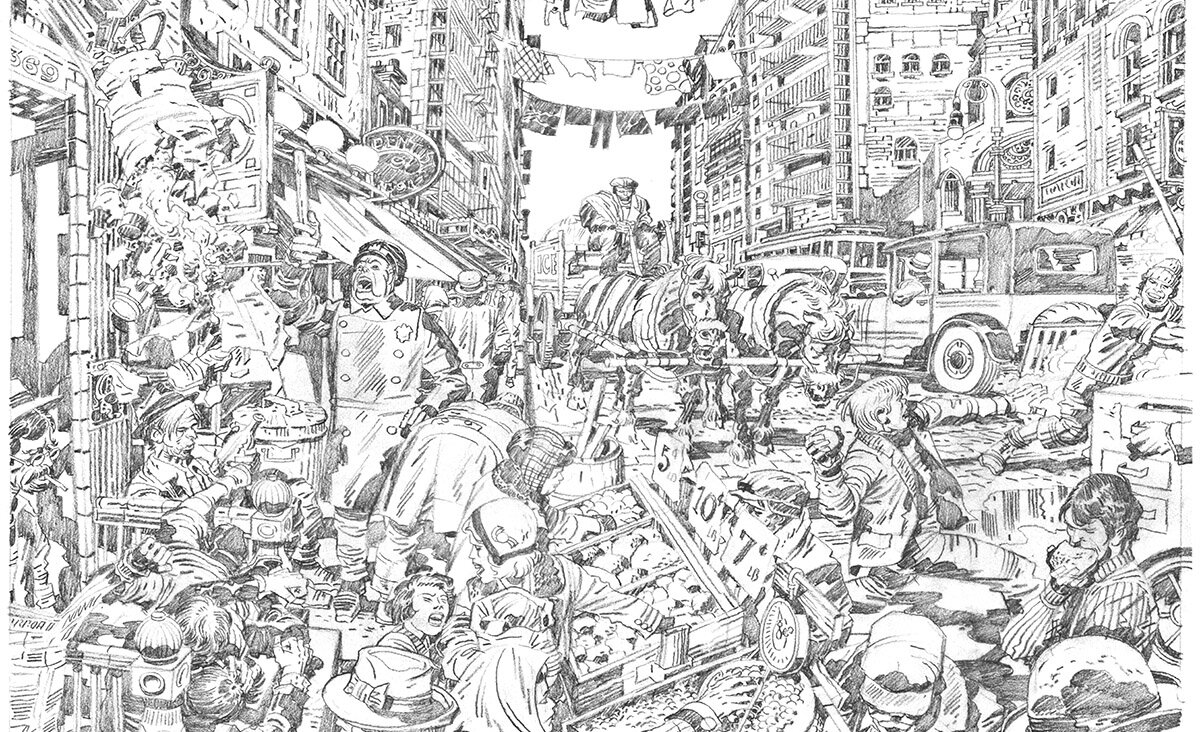

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A thrilling new exhibition about Harry Houdini pulls off an elaborate trick of its own.

“Inescapable: The Life and Legacy of Harry Houdini,” at the Jewish Museum of Maryland through January 2019, manages to make the mythical magician’s story feel fresh — an achievement that’s almost as hard as making an elephant disappear, which Houdini did.

By focusing on Ehrich Weiss — the immigrant rabbi’s son who became a global superstar — the JMOM brings a new dimension to Houdini’s inescapable story. “Houdini lived to be 52, which turned out to be 26 years of struggle and 26 of fortune and fame,” said David London, the Baltimore magician who was tapped to curate the exhibition after museum director Marvin Pinkert saw him perform. “Most bios focus on the second half of his life, which is the part we all know. I decided I wanted to treat this story more like his life, and the exhibition is pretty much split in half that way.”

More than 90 years after his death, Houdini remains a pop culture touchstone. His name is still shorthand for legerdemain and escapes, and razzle-dazzle. More than 150 biographies have purported to cover his life. Very few address his Jewish backstory.

Houdini was born in Budapest to Rabbi Mayer Samuel Weiss and Cecilia Steiner Weiss; the family emigrated to Appleton, Wisconsin, when young Ehrich was four. Rabbi Weiss led Appleton’s German-Jewish Zion Congregation; Ehrich grew up hearing Yiddish, Hungarian, and German at home, but very little English. After running away from home at age 12 — hoping to find work to support his impoverished family — Ehrich rejoined his parents a year later in New York City, where they’d moved. Some Houdini historians trace young Ehrich’s interest in magic to his father’s sermons; after seeing the rabbi hold a congregation rapt, the power of performance became clear.

And while the show doesn’t draw a straight line between Weiss’s Jewishness and Houdini’s world conquest, it evokes moving and intriguing parallels with the modern immigrant experience. “As an immigrant, it’s easy to see yourself trapped in whatever circumstances you find yourself in,” London said. “He became a symbol of people’s ability to escape from impossible circumstances. His career is a metaphor for freedom at a time when people really felt trapped.”

Houdini’s yearning for freedom from tradition even came through in his personal life. At age 18, he married Wilhelmina Beatrice Rahner, a Roman Catholic who’d been performing alongside him in a song-and-dance act called The Floral Sisters. Surprisingly for the time, Houdini’s mother accepted his non-Jewish wife

London’s tireless networking with collectors yielded a trove of Houdini ephemera on display here, from a case of original escape “tools” to little-seen personal photos to the straitjacket Houdini used in performance. But two of the exhibition’s most eye-opening artifacts appear early in the show, in the first of seven cleverly constructed sections that track Houdini’s life and career. Near a Hebrew Bible that belonged to Houdini’s father, Rabbi Mayer Samuel Weisz, sits a letter to young Ehrich’s parents, signed “your truant son”; in his first escape, he had run away from home at age 12.

“Finding that Bible, which has never been on display anywhere, was the biggest surprise for me,” London said. “It really provided a backbone for us, and it’s a way that Jewish children of today can feel connected to Houdini.”

The exhibition is taken over by magic— as was Weiss’s life — in its second section, “Metamorphosis.” Along with a co-worker from a short-lived stint in a tie factory, Harry Houdini — named for French magic pioneer Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin — began performing at tiny venues, from basements to beer halls. The section title refers to a signature illusion, where a magician trapped in a trunk “switches places” with his colleague outside.

Image by Courtesy of the Jewish Museum Maryland

As the exhibit’s third section, “Opening Acts,” makes clear, Houdini faced years of desperation before finding fame. A nickname he despised, “Dime Store Harry,” referred to his shows at museums that showcased human oddities. Another astonishing relic, Houdini’s handwritten journal, chronicles his hardships; “Rain hard. No dinner,” an entry from August 1898 reads.

In “The Self-liberator,” the exhibit begins to chronicle the meteoric rise of Houdini’s career. Spotted by vaudeville impresario Martin Beck at a Minneapolis beer-hall performance, Houdini quickly snagged a contract and dates that took him to prestigious West Coast theaters. It’s fascinating to see artifacts like Beck’s contract for the performer, as well as Houdini’s rider for London performances — for example, “80 gallons of water which must be lukewarm.”

As Houdini’s fame soared, he cannily broadened his repertoire to include highly promotable jailbreaks and prison escapes. A case of original handcuffs and keys adds dimension to the story; a bent hairpin Houdini used to break free of hardware feels especially poignant.

The exhibition spends much of its last third detailing Houdini’s eye-popping stunts and elaborate escapes, including his infamous vanishing-elephant trick, which gets explained in an ingenious miniature model. But the most revealing chapter of “Inescapable” comes near the end, with an exploration of Houdini’s “deep commitment to fellowship and brotherhood.” Along with a magicians’ society in the United States and a magic club in the United Kingdom, Houdini used his clout to establish The Rabbis’ Sons Theatrical Benevolent Association, a fraternal organization that raised money for war efforts and other charities. Among the other “rabbis’ sons” he corralled were Al Jolson, Irving Berlin and all of the Three Stooges. An original invitation to a Rabbis’ Sons function brings the group to life.

At the end of his life, Houdini dedicated his energy and skill to exposing fake spiritualists; mediums were springing up across America to “deceive grieving families, provide false hope, and take their money.” Houdini even took to wearing disguises to attend seances, inevitably debunking their organizers.

For someone who flirted with death so casually, Houdini died in an especially senseless way; at a performance in Montreal, a McGill University student punched him in the stomach, taking up a challenge Houdini had long floated about his invulnerability. Houdini died on Halloween 1926 of complications from a ruptured appendix.

If some of “Inescapable” sounds arcane — or of primary appeal to Houdini obsessives — it’s not. The JMOM may be a tiny regional institution, but it’s assembled a world-class show that opens a new window on an icon whose stories all seem to have been told. From that perspective, David London and the museum crew have performed their own feats of magic. “Others have told the stories of the legend. We’re telling the story of the person,” London said. “Uncovering those bits of his Jewish heritage was one of the most exciting things I’ve ever done.”

‘Inescapable: The Life and Legacy of Harry Houdini,’ runs through January 21, 2019 at the Jewish Museum of Maryland.

Michael Kaminer writes frequently about the arts for the Forward.