The distressing truth behind an exhibit about antisemitism — it’s always timely

In a Tribeca gallery, 21 artists confront an issue that was relevant long, long before Oct. 7

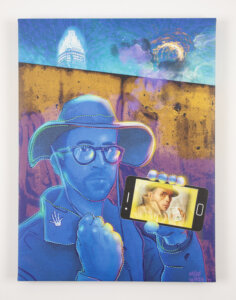

Marina Heintze’s “Yitler” combines the faces of two known antisemites. Courtesy of 81 Leonard Gallery

The first thing you see when you walk into 81 Leonard Gallery in Tribeca is an uncanny amalgamation of two faces: Adolf Hitler and Kanye “Ye” West. Is it a powerful dictator or a popular rapper? It’s both and neither, but a face and font of antisemitism regardless.

Marina Heintze’s “Yitler” is like an artistic onion — peeling back one layer reveals another and each pungent revelation adds to the sting. Bacterial patterns remind viewers of propaganda that has long associated Jews with disease. Tattoo paper and distorted shoes conjure images of Auschwitz.

Two other pieces by Heintze greet passersby from a front window looking out onto Lower Manhattan, home to dozens of art galleries and growing. One features a portrait of Heintze’s grandmother, who fled Vienna and the Nazis, and the other an array of literal dog whistles. All three are part of a series conceived of before Hamas launched its attack on Oct. 7. But the subject matter, Heintze says, is unfortunately “always on trend.”

Making art is “the only way for me to express either my disdain or my point of view and feel maybe that I can do something with that,” said Heintze, who grew up in Tribeca but now lives and works in Los Angeles. “Antisemitism is a disease and that’s what I wanted to relate to with the material that I chose,” she added. “And if it’s a disease, there has to be a cure.”

Heintze doesn’t claim that art is that cure, but for her and several of her colleagues participating in the “Artists on Antisemitism” exhibition (on view through Aug. 30), it is a necessary outlet for expression and a chance to find one another at a time when fellowship isn’t forthcoming everywhere in the art world.

“My whole idea for the show was that it had to be something that would help everybody,” said Yona Verwer, one of the curators.

‘Antisemitism didn’t start with Oct. 7’

Verwer began reaching out to artists she knew in Israel in the aftermath of Oct. 7 to say she was thinking of them and to offer support. In return, she got art and stories: “I thought, ‘We have to do something. We have to do a show about the aftermath.’”

That “something” turned into multiple planned shows, starting with “Artists on Antisemitism,” which became more pressing as protests and antisemitic incidents escalated across the country.

The show was curated by Verwer; Jewish Art Salon members Judith Joseph and Ronit Levin Delgado; and Hannah Rothbard and Nancy Pantirer, director and founder of 81 Leonard Gallery, respectively, both Jewish artists themselves. It’s the second such collaboration between the Jewish Art Salon and the gallery, after 2022’s “PAUSE: Jewish Heritage Month/Ways of Being,” which highlighted “the multiplicities of Jewish identities,” Rothbard said.

The submissions the curators received in response to this call — framed intentionally around the current surge of antisemitism rather than the Israel-Hamas war — also reflected a diverse group of artists with different perspectives. In the end, the curators chose works by 21 artists from all over the U.S. and Israel, spanning generations, and working in mediums including photography, painting, paper collage, woodcut, mixed media, and even Lego.

“Antisemitism didn’t start with Oct. 7. So this is a conversation that has been needed to be had regardless,” said Rothbard. But it did feel particularly important to offer the space and opportunity at a time when, she said, “the New York art world seems to treat Israelis and Jewish artists like they are the State of Israel and like everyone is a stand-in for the conflict.”

As the curators put together the show, they realized much of the work grappled with dualities, like “caution versus courage,” Rothbard said. That tension fills the gallery, as does that between past and present, tragedy and joy, fear and pride, despair and optimism. Each work contends with antisemitism in its own way and on its own scale.

“Neck Piece,” for example, is a pair of small paintings — eight by eight inch squares — by Goldie Gross. Both are close-up self-portraits that zoom in on the hollow beneath the artist’s chin and let viewers spot a subtle difference. On the left, a necklace is tucked under Gross’ collar, mostly invisible behind her black shirt. On the right, the gold chain sits in plain view, Hebrew letters spelling out her name.

“My name is my name and my name is Jewish,” Gross told me. Initially after Oct. 7, she said she was afraid to wear such an obvious signifier of her Jewishness. But eventually she decided to put it on anyway. “The difference between saying my name is Goldie and wearing my name Goldie on my neck in Hebrew — one might be an accident of birth and the other is a conscious decision.”

“I was not expecting it to be so relatable,” she said. But this question — to wear or not to wear visible Jewish symbols in public — has been on the minds of other American Jews, too. In a recent survey, 39% of respondents said they felt safe doing so, while 42% said they didn’t.

When Gross broke her arm and had to pick one necklace to don for the foreseeable future, she landed on the Hebrew letters. “I chose Goldie because f–k it, what’s someone going to do? I carry pepper spray.”

So does the subject of a paper collage in the show. “My Friend in Crown Heights,” by Dan Harris, is a portrait of the midsection of a man carrying a baby whose footie pajama-ed fisalach is visible in the frame. Hanging from the father’s belt loop is a pepper spray keychain swinging among the strands of his tzitzit. A quotidian snapshot of a new old reality.

Nearby, a tiny Lego figurine is encased in glass. “Emergency Golem,” says a label affixed to the top of the small frame. “It’s a safety device, just like a fire extinguisher,” said the artist, Maxwell Bauman, who reimagined the 16th century protector for contemporary times.

“It wouldn’t be enough to put out, say, a forest fire, like the forest fire of hate that we’re dealing with right now. But it would be enough for, say, your curtains catching on fire ‘by accident,’” he added. “It’s something small but powerful to protect you.”

Of the metaphorical forest fire, Bauman said: “It’s never really felt this bad.”

‘The more things change’

The exhibition is a collection of artistic responses to a phenomenon that predates Oct. 7 by thousands of years. As Joan Roth put it in the title of one of her photographs on display, of a man walking past antisemitic graffiti in Lviv in the early aughts: “The More Things Change — The More They Stay the Same.”

But the show is also deeply connected to the events of that day and even more so to the renewed wave of antisemitism in the last nine months.

For a week or two after Oct. 7, Ronit Levin Delgado felt like she couldn’t function. A multidisciplinary artist who came from Israel to the States on a Fulbright scholarship over a decade ago and stayed to live and work here, she was far away from her family and friends, one of whom was killed in the attacks. At the time she was participating in an arts residency on Governors Island. She heard from two other Jewish artists, but says no one else reached out.

“I lost — I do like the quote unquote — I ‘lost’ a lot of artist friends,” she said.

In those early days in October, she felt frozen and alone. What revived her, she said, was getting involved with activism for the hostages and using her art as a tool, both for herself and for those who might view it.

She embraced the opportunity to help curate the current exhibition and come together with the other participating artists for the opening, a Shabbat dinner for Jewish women in the arts, and other events. “It’s like when you want to cry and laugh at the same time,” she said. “Each artist is telling their own experience, and we are all there to hug them and say that we love them and we support them.”

“I want to say, I wish we’d have more of these,” she said. “And then I want to say I wish we wouldn’t need to.”

Her piece, like so many others in the show, manages to do two seemingly contradictory things at once. It acknowledges the tragedy and trauma that is so often the result of antisemitism. And it exudes pride, optimism, joy, and life — in this case literally. She’s spelled the Hebrew word chai, or alive, using kisses, her materials being lipstick on paper.

“Our essence is to — despite everything — overcome, to prevail,” she said of the Jewish people.

“Now I feel like I’m slowly going back from this depression mode to think that we will prevail. We will dance again. Our love will rebuild,” she added. “Our highest value is happiness and to celebrate life. And that’s exactly what I want to continue to focus on.”