Hidden away for a decade, a beloved Jewish artist’s mural awaits its return to the public eye

Ben Shahn’s 13-piece ‘Resources of America’ at a former post office in the Bronx, has been inaccessible since 2014

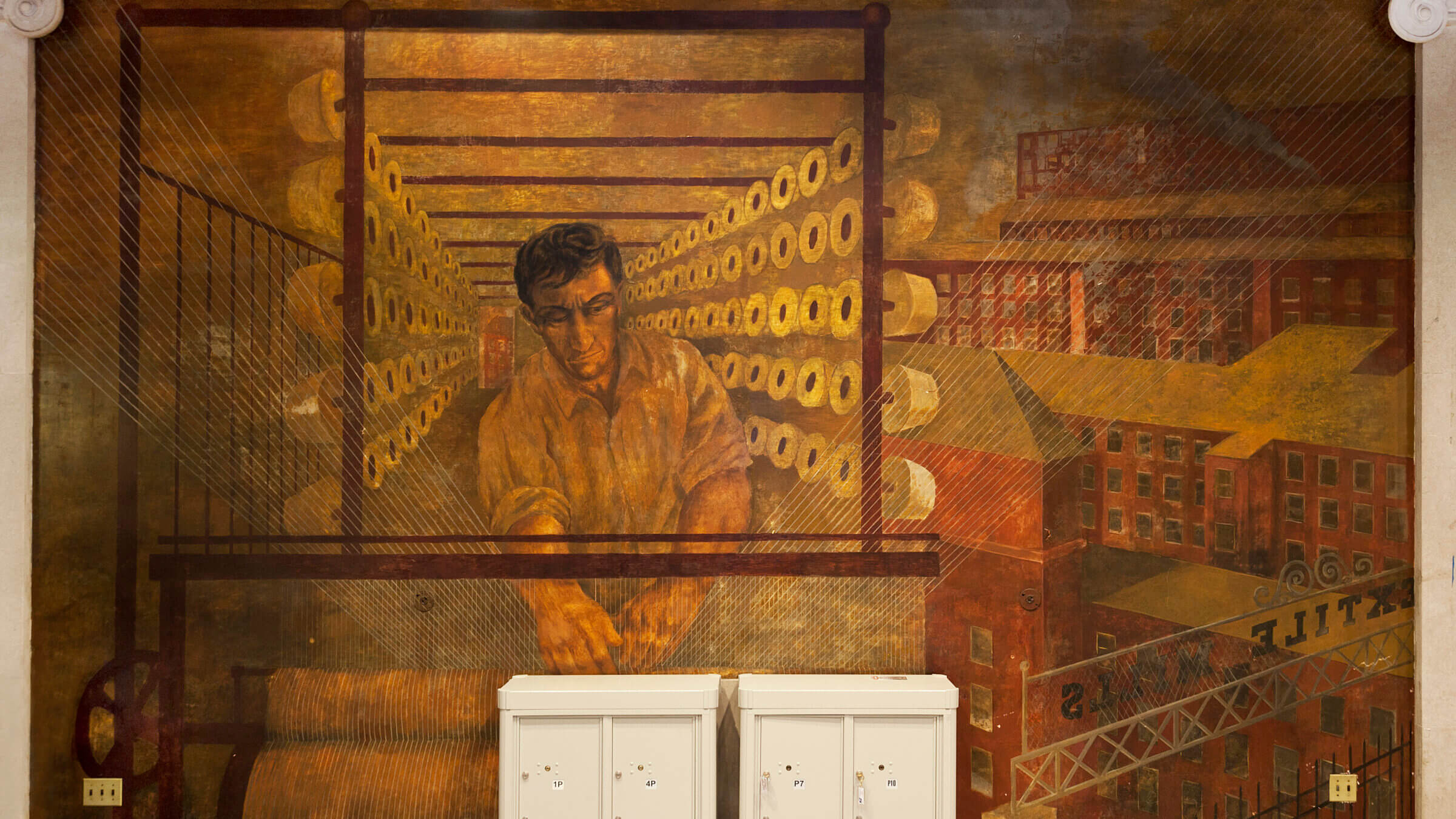

‘Man working a mechanical loom’ in Ben Shahn’s ‘Resources of America’ mural. Photo by Joshua Nefsky

Murals, of course, are created for the public. They’re for anyone who happens to pass by — to absorb, explore, think, and learn from what they engage with.

But for the last 10 years, “Resources of America,” an important 13-piece mural inside the former Bronx General Post Office, has been almost impossible to see. The mural was created between 1938 and 1939 by Ben Shahn, one of the most productive and politically expressive artists of the 20th Century, and his wife, Bernarda Bryson, also an artist.

Since the giant post office building was sold in 2014, the murals have been inaccessible to the public. And now that the historic structure is once again on the market, it’s still unclear when anyone will be able to see them again.

The status of the building

The U.S. Postal Service sold the building, on the Grand Concourse and East 149th Street, to a New York City developer, Youngwoo & Associates, in 2014 for $19 million. They had plans to turn the landmarked post office into a shopping structure with retail stores and restaurants, as well as offices.

Nothing much has changed in the 173,000-square-foot structure since that purchase — there’s still a Cuban restaurant on the roof and a much smaller post office. But in 2019, Youngwoo announced it was selling the building to MHP and Banyan State Capital for $70 million. That sale eventually fell through and the building is once again for sale. Visiting the site recently, I could only see two of the 13 murals through the locked glass doors that separate the new, smaller post office from the old General Post Office.

The decade-long delay comes at a time when art like Shahn’s does not just express history but is also incredibly relevant to the current crises that threaten democracy in the United States and abroad.

The murals

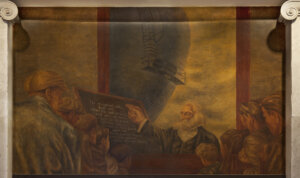

Focusing on the United States as a whole, rather than just the Bronx or New York City, Shahn’s mural highlights American blue collar workers, from its farms to its factories. In her book, Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene, Diana L. Linden, an American art historian, writes that in this mural, Shahn “chose to depict workers across America to counter what he perceived as New York’s urban provincialism.” That way, he could connect Bronxites with “workers and in regions and industries beyond New York City.”

Shahn was born in Lithuania in 1898. In 1906, when he was 8, his family emigrated to the U.S. and lived in Williamsburg and other Brooklyn immigrant neighborhoods. He had to leave high school to support his family but he took up lithography in a Manhattan workshop. And so began an artistic career that lasted more than 50 years.

Shahn’s artwork could be playful, festive, while also simultaneously wrenching. He painted whatever inspired him, such as a man playing harmonica on a leafy hill (“Pretty Girl Milking the Cow” 1940) or “Girl Skipping Rope” (1943) in which a girl skips in front of a building with missing windows and bricks during wartime. Much of his work was overtly political, focusing on issues like civil rights, economic injustice, and the Holocaust.

“Identity” (1968) features raised, joined hands protesting the Vietnam War, using unique Hebrew lettering; a series of paintings illustrates the threat of nuclear war in the early 1960s. Amid the happy and even horrific, there are always Shahn’s unique forms and combinations of colors and shapes.

The Bronx post office mural is not about injustice; instead, it focuses on workers on farms and in factories, riveters, textile workers. One of the panels features a female worker, a rarity in that time as she is presented as a paid industrial worker, not as a helper to her spouse or homemaker.

The battle over the mural

Yet, as Linden explains in her book, Shahn’s work ignited fierce opposition.

In the late 1930s, one panel triggered the ire of Rev. Ignatius W. Cox, of Fordham University, and his followers. Speaking to 3,000 parishioners at the Church of Our Lady of Angels in Brooklyn, Cox objected to the religious skepticism on display in Shahn’s depiction of Walt Whitman, reading a section of his poem, “As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free” to a gathering of working-class men:

Brain of the New World, what a task is

thine,

To formulate the Modern—out of the

peerless grandeur of the modern

Out of thyself, comprising science, to

recast poems, churches, art,

(Recast may-be discard them, end

them, may-be their work is done, who

knows?)

By vision, hand conception, on the back-

ground of the mighty past, the dead,

To limn with absolute faith the mighty

living present.

“The wording is an insult to all religious-minded men and to Christianity,” Cox said. “It does indulge in propaganda for irreligion. As such the mural should never be executed.”

Shahn had the backing of the federal Treasury Section of Fine Arts, which funded and oversaw many mural projects at that time (and were more competitive than the other New Deal mural projects). The Section funded other murals by Shahn, including ones in St. Louis and in Queens. But that support eventually dissipated as Rev. Cox and his followers refused to relent, writing letters to the Postal Service and taking part in demonstrations. The antisemitic Catholic priest, Father Charles Coughlin, also vocally opposed the murals.

To quell the controversy, Shahn eventually relented to an extent and agreed to use a shorter and less controversial excerpt of a Whitman poem — “As I Walk These Broad, Majestic Days”:

For we support all,

After the rest is done and gone we remain,

There is no final reliance but upon us,

Democracy rests finally upon us,

(I, my brethren, begin it).

And our visions sweep through eternity.

Shahn’s painting, “Myself Among the Churchgoers” (1939), directly addresses the mural battle. It features three women, all in black, walking by a church with their heads down, as a large man approaches with his back to the viewer, appearing to exert control. Shahn himself appears a bit beyond the group, in a light brown jacket with gray pants and white shoes. He faces the street, with his camera pointed at the walkers. The church’s signboard reads, “Is the Government Sponsoring Irreligion in Art?” — the title of one of Cox’s sermons.

On display in Spain

While many American museums exhibit Shahn’s work, and three had major shows at the turn of the millennium, the first career-spanning retrospective of Shahn’s work in the Western art world, since the Jewish Museum’s traveling exhibition of the late 1970s, was held recently in Spain at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid.

“Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity,” which included 200 works of art and 100 items of ephemera, was widely praised for its focus on social justice and Shahn’s outspoken stances on war, racism and other struggles.

“At a time of great global turmoil, ‘On Nonconformity’ offers the stark reminder of our common humanity that Shahn called for more than 70 years ago,” Lauren Moya Ford wrote in Hyperallergic.

“He used his art as a weapon in the class struggle and, after joining liberals in Popular Front coalitions, as a vehicle to fight fascism abroad and to denounce its manifestations at home,” Laura Katzman, a professor of art history at James Madison University in Virginia, and the exhibit’s guest curator in Madrid, wrote in her essay for the exhibition.

“Perhaps this is why so much of his work feels so significant today: He found a way to represent the essence of momentous feeling and events,” wrote Ford. “Shahn’s works don’t just respond to the atrocities of his own time; they have the uncanny ability to continue to speak to the ones of our present day. And in the process, they ask us to urgently do something.”

The current status of the mural

While Youngwoo didn’t reply to requests for more information about Shahn’s post office murals and the status of the building, Sam Goodman, a long-time urban planner at the Bronx Borough President’s office, said that “the bottom line is they couldn’t find people interested in rehabbing the building.”

Goodman added that there’s long been a shopping complex three blocks away and that there’s a $35,000 median household income in the area, which would make it hard for Youngwoo’s development project to succeed. But, he said in an email, “This is likely to change as over 2,000 units of housing will be opening within a few years (less than three).”

“It will be interesting to see if anyone makes an offer on it,” Goodman said.

Preserving the mural

Before Youngwoo & Associates formally acquired the Post Office in 2014, Katzman and Jonathan Shahn (Shahn’s and Bryson’s son) succeeded in convincing the city’s Landmarks Preservation Corporation (LPC) to landmark the inside of the post office to protect the mural.

So, New York City law would require that “any new application to alter or permanently remove the murals in the designated interior spaces would require review and approval by the full Landmarks Preservation Commission after a public hearing.”

Because restoration of the mural was a required part of any eventual sale, the USPS hired Parma Restoration to restore the mural “prior to the site’s designation as an interior landmark and subsequent sale in 2014,” according to LPC. (A Bronx news site, welcome2thebronx.com, reported on the restoration and took photos of the process). LPC recently returned to the site and confirmed that the mural is still in good condition.

Meanwhile, what was meant to be a permanent exhibit in a public space will continue to be off-limits, as it has been for the past decade, until the giant structure is sold and redeveloped. Shahn scholars and followers hope it will be as accessible to the public as it was in the past.

“Looking at our history and where we were then, it’s an important lesson for today,” said Susan Chevlowe, Chief Curator and Museum Director at the Derfner Judaica Museum. Chevlowe curated a major Shahn exhibition in 1998 at The Jewish Museum in New York. “I think about that moment in American history and our need to reflect on it and preserve it, teach it and make it available for people to know and understand.”

“The moment that we’re in, in terms of the rise of the right-wing movements in many parts of the world including in established democracies, I would say that Shahn reminds us of the dangers of authoritarianism, and his focus on the support of workers and ordinary people and the dignity of their labor and their lives,” Katzman told me. “To me, that mural is a great example of what he supported.”