Ben Shahn Was a Propagandist and Proud of It

Image by Wikimedia Commons

Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene

By Diana L. Linden

Wayne State University Press, 184 pages, $44.99

Albert Einstein disembarking in America alongside anonymous impoverished refugees. Prescient views in 1939 of concentration camp prisoners in Nazi Germany. These are just two of the indelible images created on a monumental scale in murals by the American Jewish artist Ben Shahn. In “Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene,” Diana Linden, a California-based art historian, emphasizes how Shahn, although best remembered today for such strong graphic achievements as “Haggadah for Passover,” “The Alphabet of Creation” and images honoring the anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, also produced larger-scale works perhaps even closer to his artistic essence.

A firebrand and activist from childhood on in Lithuania, at age 6 if he saw “anything in uniform, be it a letter carrier or a policeman, [Shahn] would run up… and yell, “Down with the Czar!” and then run away,” as he would later recall. As a more stable and permanent way of flouting authority, Shahn saw murals as ideal, and revelled in the notion of propaganda, as he told an interviewer from the Archives of American Art in 1968:

“Propaganda is to me a noble word. It means you believe something very strongly and you want other people to believe it; you want to propagate your faith. And it certainly isn’t a terrible thing when on the Piazza d’Espagna [in Rome] there’s the building that is for the propaganda of the Church. I don’t think any Catholic considers that propaganda in the same sense.”

Yet Catholics did protest Shahn’s murals in the Bronx’s main post office. They were painted in 1937, and only in 2013 were they declared interior landmarks with protected status by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Initially, Shahn planned an image of the poet Walt Whitman, “with his flowing beard, resembling a hybrid of Karl Marx and Moses,” as Linden notes. Shahn’s Whitman gestured to a blackboard with a quotation from his poetry about art and workers. But Whitman’s writings were on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books, and in a 1938 sermon, the Rev. Ignatius W. Cox of Fordham University claimed that the Whitman quote represented “propaganda for two false and fatal pseudo-messianic movements which are competing with Christianity for the allegiance of men’s mind. They are Bolshevism of the Russian Asiatic type and Nazism of the European type.” In response to the irony of being accused of promoting Nazi ideology, Shahn made a public statement:

“With democracy rather on its mettle these days, it gives one quite a shock to hear ‘verboten’ directed against a traditionally American poet…. One must protest that Whitman is one of our most honored and loved American poets. He is a part of our cultural tradition.”

Shahn ultimately selected a different Whitman text, not mentioning workers, to be reproduced.

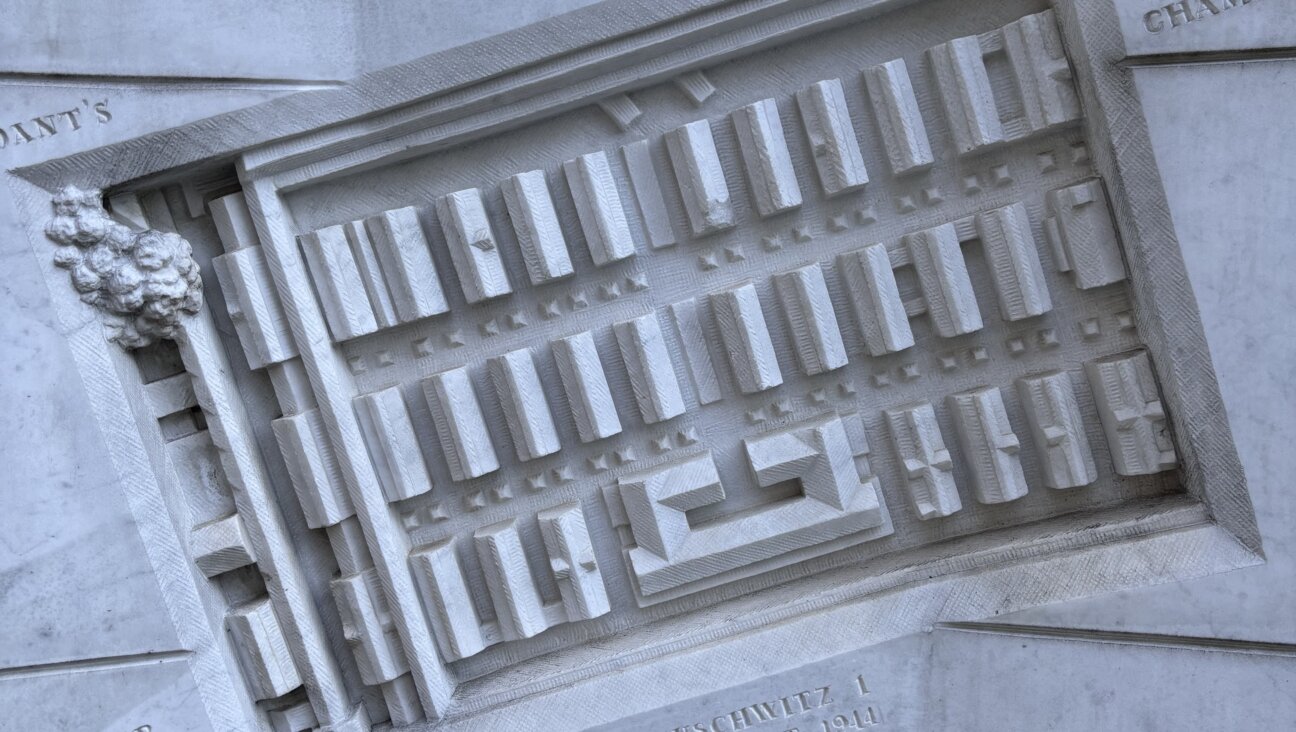

The German word verboten, meaning “forbidden,” also occurred in Shahn’s mural painted in from 1937 to 1938 for the community center of Jersey Homesteads (today called Roosevelt), New Jersey. The town was intended to house Jewish garment workers, and Shahn’s mural, according to Linden, echoes the Haggadah’s narrative of slavery, deliverance, and redemption. Shahn included anti-Semitic placards and other imagery from the Old Country, with Albert Einstein and Shahn’s own mother leading immigrants down a gangplank to Ellis Island.

An avid reader of the Forverts who clipped and saved articles and editorials about the growing tragedy in Europe, Shahn was ultra-aware in the 1930s of the threat posed by fascism. A never-realized 1939 mural project for the post office of St. Louis included images of pogroms and of prisoners behind barbed wire fences in concentration camps. Although extermination camps were not yet in operation, Shahn hoped — in vain — that such imagery might persuade American officials to repeal laws severely limiting the immigration of Europe’s endangered Jews.

Shahn was perceptive and even prescient about political matters, yet he could be relatively obtuse about gender issues, Linden asserts. In the Jersey Homesteads murals, Shahn was “historically inaccurate, or blindly chauvinistic,” she charges, “when he painted the garment factory workers as almost exclusively male… when in fact women and girls were known as gallant labor activists and organizers who walked many a picket line. His representation of male workers as the rank and file is consistent with the gender biases of New Deal art… Shahn was more cognizant of class issues than gender issues.” On a more personal level, Linden notes something that occurred in the mid-1930s:

“While working at Rivera’s side at Rockefeller Center, the married Shahn met Bernarda Bryson, a young artist and writer for the Daily Worker and an ardent Communist. Shahn was so taken with the like-minded Bryson that he left his wife, Tillie [Goldstein], and abandoned his two young children both emotionally and financially.”

If flawed on a human level, Shahn maintained fierce artistic ideals, as described in his lectures at Harvard University, “The Shape of Content”. Benefiting from the Federal Art Project (1935–43), a New Deal program that President Franklin. Roosevelt launched by to assist struggling artists during the Great Depression, Shahn learned fresco techniques from the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, whose wall works were internationally popular from the 1920s onward. Yet Rivera, who claimed to be of Jewish descent, did not represent an artistic ideal for Shahn. As Shahn told an interviewer from the Archives of American Art in 1965:

“I had arguments with [Rivera]. For instance, I felt that he was crowding his things too much, just cluttered; and I said so. He said, ‘Well, look around you. Do you see any space?’ In a sense it’s true, you know. As I look around now, I see those blueprint cabinets, the books over there, and if one were to photograph it, it would be a clutter. But I always felt that the role of the artist is to bring an order to disorder.”

From a painterly point of view, he preferred Rivera’s rival Mexican muralist, José Clemente Orozco. Nor did Shahn appreciate being classified with other Jewish artists simply because he was Jewish. As he would declare, “I don’t share anything with [Marc] Chagall.” He was even less enthused on a personal level about the American Jewish sculptor Chaim Gross, whom he accused of obtaining surreptitiously Shahn’s sketches for a never-realized 1935 mural for Rikers Island, selling them for profit:

“There was a very canny gentleman by the name of Chaim Gross, a sculptor, who knew where [the sketches] went and bought them up. The last time one of them was sold, it brought $3,500. I got pretty bitter about it, that this character [Gross] has always scavenged around art, you know, and knew his way… I have difficulty controlling myself when I see him.”

Such personal feuds and peccadilloes aside, Shahn’s noble legacy remains in the distilled power of his wall paintings, embodying his artistic principle of plain speaking as he formulated it:

“Murals are visualizations of strong but simple ideas. They have to be that, just as simple as you can really make them. If they get too complex, if the idea gets too complex, they are seen almost like billboards. They have to have that kind of simplicity.”

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO