How the war changed an artist’s life, his politics — and his painting

Before Oct. 7, Sam Griffin’s work was personal and introspective; then he was drafted into the Israeli army

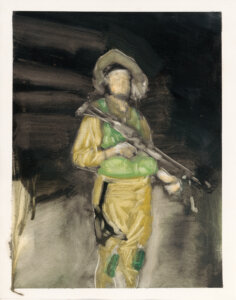

‘Aftermath,’ an exhibit of Sam Griffin’s post-Oct. 7 oil paintings, is currently on view at the Bernard Heller Museum. Courtesy of Bernard Heller Museum

In a post-Oct 7 world, Sam Griffin, who served a tour of duty, first in the southern Gaza Envelope for two and a half months, and then for one month in the Southern Gaza Strip, has evolved as both a human being and a painter.

“Before, I was a British-born painter living in Israel,” he said. “Now I am an Israeli painter.”

The articulate, heady, and amiable 35-year-old artist met with me at Hebrew Union College’s Bernard Heller Museum where Aftermath, an exhibition of 14 of his post-Oct. 7 oil paintings will be on display until the end of June.

Griffin’s work consists mostly of large landscapes — some rural, others urban — all of which seem to take place during an ominous dawn or dusk, amid a sense of impending doom and intense isolation. An unknown disaster has just occurred or is about to take place. The canvases are covered with agitated, rapidly applied brush strokes coupled with the blotting off and wiping out of previously layers of paint.

“I’m finding beauty in the horror without being too specific,” Griffin said as I sat with him and Heller Museum director Jean Bloch Rosensaft and Ram Ozeri, founder and director of the Jerusalem Biennial where Aftermath was exhibited as a solo show in 2024. “The paintings are a window into what I was looking at. I wanted to leave space for the viewers to step in and interpret the pictures in their own way. No, they’re not political paintings.”

“Sam brings us into the heart of darkness,” Rosensaft said. “The rubble beneath the gorgeous blue skies, the sunrise, the flares. Those liminal moments. It’s heart-wrenching. At the same time I’m awed by Sam’s capacity to put it on canvas and express tremendous resilience and an embrace for life. I felt it was so important to show this work in this moment, which has the capacity and strength and hope to break through the news. It is at once a particularly Israeli theme and a universalist theme.”

The paintings are notably devoid of people, short of a faceless soldier or two featured in a few pieces. Among these is a faceless self-portrait of the artist.

Griffin is drawn to faceless figures. Like his earlier “Wise Old Men” series in which Griffin was searching for a literal, spiritual and existential connection to grandfathers he had never known, here too he was seeking to evoke a deeply personal and global image.

Though, in the Aftermath paintings, he stressed, “These are not archetypal soldiers in an archetypal war — they are archetypal Israeli soldiers in an archetypal Israeli war. Israeli wars are different from other wars. Wars are forced upon us. In both the Yom Kippur War or the current war we were attacked. We are the most peace-loving people, especially those living in a kibbutz. They want to serve as the bridge. It’s the safest place in the world. For something so horrible to happen here…”

A turning point moment

The son of a cartoonist and surrounded by art books, Griffin grew up in south east London and started to draw at an early age. “Lucien Freud was the first painter I saw that made me decide I want to paint,” he said. “Jake Ward-Evans is a contemporary British painter who inspires me today. Most of all, my influences are from the Spanish and Dutch Baroque period: Rembrandt, Velazquez, El Greco, Rubens, Caravaggio and Tiepolo.”

Growing up he defined himself as a secular Jew, “always proud to be Jewish, but certainly not observant,” he said.

In 2006, he traveled to Israel, wanting to experience the country, but mostly because he thought it might be “fun.” He says the experience was life-altering — especially when he “touched the stones at the Western Wall.”

“Suddenly I felt I was a link in a chain,” he said. “That was a turning point moment.”

When he returned to England, feeling more Jewish than ever, a profound curiosity about religious observance — its discipline, practice, ritual and spiritual elements — surfaced as well. And he found them most deeply expressed and embodied in Orthodox observance. In 2010, he decided to make Aliyah.

“I wanted to live among Jews,” he said. “I wanted to join the IDF. I wanted to experience the camaraderie and contribute to Israel. My parents were supportive, though they were not that happy about my serving in the military. My mother hoped I would meet a nice Jewish girl.”

(His wife, Rachel, a Washington, DC native, is an obstetrician and the couple are parents to three small boys.)

In Israel he spent the first six months on a kibbutz, working, and learning Hebrew. In 2011 he began his two year tour of duty in the army’s infantry combat unit. “It was a deep dive into Israeli culture for sure,” he said.

On Oct 8, just one day after the Hamas terrorist attack, he was drafted. Like most other soldiers, he explained, up until that point he had just been living his life — as a husband, father and painter.

“Most Israeli soldiers are not into military careers,” he said. “They are artists, start-up tech people, electricians. Yes, there is an admiration and appreciation for soldiers, but there’s no reverence because we’re all in this together.”

It’s a universe where the odds of being called up to the front are ever present. Still, there was nothing that could have prepared him for the actual experience in southern Gaza. Not only was the experience traumatizing, he said, it was emotionally paralyzing.

“At the beginning I was stationed in a settlement in a small village in southern Gaza to secure the area and border,” Griffin said. “We were concerned that Hamas would go from southern Gaza to Egypt and then back into Israel. We moved from settlement to settlement, entering buildings not knowing if we’d be ambushed by terrorists at any moment. And at night, I’d follow the news on my phone, seeing the horrible images and listening to the lies. We were all constantly afraid of what was coming next.

“I began to take photographs and do small sketches as a way to calm myself. But when I returned home without any transition between being a soldier in Gaza and diapering the baby — that’s when the real trauma began. I was tense and short-tempered and my ability to regulate my emotions was severely diminished. I knew I needed to come back to myself to be a husband and father.”

With the help of friends, family and therapy, Griffin began a long and arduous process of healing. Finally he was able to paint again using the photos he took and the sketches he drew in Gaza as inspirations for the larger pieces. These paintings were at once aesthetic extensions of his previous work and departures. His subject matter and the mood of the paintings had shifted away from some of his earlier work which was more personal and introspective.

“My colors now are bolder and the composition is more influenced by the old masters,” he said. “Artists don’t stand alone. They are part of a contemporary conversation and a tradition. It’s the artist’s responsibility to learn from that tradition. For me to say I’m doing something new would be arrogant. I stand on the shoulders of giants.”

A change in focus

Griffin has recently turned his attention to biblical themes in his paintings, such as “Yaa’cov and the Angel” and “Elijah’s Ascent,” and he speculates that the next chapter in his art will center on religious themes and narratives.

“For me Jacob’s struggle very much embodies the Israeli experience,” Griffin said. “They very much want to live peaceful, simple lives, but at the same time they are struggling with that part of them that is the soldier, that needs to be the soldier. It’s an ongoing internal battle.

“The past year and a half made me want to go back to the spiritual source of the Jewish people and seek truth. There’s a lot of untruth in the world directed towards Israel. Generations of persecution and now the uptick in antisemitism. People deal with this in different ways. My way is to go back to the scriptures and try to draw some meaning from it. To understand myself better.”

As his paintings have moved in a new direction so too have his politics and relationship with religious texts.

Griffin said he has grown more “politically conservative.”

“We stand alone in the world and need to look out for our family, our community and ourselves as individuals, our mental and spiritual well-being,” he said. “I have a more fundamentalist relationship to the Jewish texts. I see the Torah as Divine. I see the Torah as Truth.”

Griffin says he wondered if Jewish American viewers would interpret his art through a lens that was singularly different from that of their Israeli counterparts and was surprised by how similar the reactions were. He attributes this unity to the current cultural and political climate and a sense among Jews of all stripes that they’re members of a small vulnerable and besieged community.

“It doesn’t matter if you are Reform or Orthodox or Israeli or non-Israeli,” he said.

However, when I wondered aloud if his work might be exhibited today outside of Jewish themed galleries, he said he didn’t know.

Ozeri told me that Israeli artists are now being discriminated against and barred from exhibitions elsewhere. He cited an example from the Venice Biennale in which fear of protests and vandalism led to the closing of the Israeli pavilion.

“You have exhibitors who have ideological objections to Israel and won’t exhibit the work of Israeli artists. But you have just as many, maybe more, who simply don’t want the bother of dealing with hostile responses that might erupt if Israeli works are displayed,” Ozeri said.

At the opening reception for Aftermath, James Snyder, who leads the Jewish Museum in New York, spoke of the way art evolves in times of war — how World War I led to the rise of surrealism and dadaism, and how abstract expressionism and minimalism emerged after World War II.

When I asked Ozeri if Israeli art might change post-Oct. 7, he said he was sure it would but didn’t know exactly how.

“Perhaps Israeli paintings will be more Biblical and or identity based,” Rosensaft said. “Before Oct. 7, much of Israeli painting was universalist or escapist. Maybe there will be a return to reality. I am very curious as to how art, dance, and theater will express current history and also transcend it.”

“Israeli art is mostly very conceptual,” said Griffin. “I would love to see painting become a more popular medium among artists in Israel. I will be continuing with the biblical themes and narratives for the foreseeable future. This might evolve into something else, but for now, this is where I am.”

When “Aftermath” completes its run at HUC it will launch a national tour to venues in Omaha, Los Angeles, San Diego, and HUC’s Skirball Museum in Cincinnati.