Ben Shahn was a radical artist — why didn’t he want to be called a Jewish one?

A new retrospective at the Jewish Museum finds an artist whose Jewish identity was linked to a questioning crusade for justice

Ben Shahn, Study for Jersey Homesteads mural, c. 1936. The image tells a story of Jewish immigration. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

In the companion catalogue to Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, a new retrospective of the social realist artist’s work at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan, we learn he didn’t like being called a “Jewish artist.”

That he found the label limiting is no wonder. In a 50-year career, Shahn proved to be one of the most fluid of American artists. His work, in graphic design, magazine covers, museum works, posters, municipal murals and street photography show remarkable range.

In the essay that gives the exhibition its name, delivered as part of a lecture series at Harvard in 1957, Shahn stated that “nonconformity is a precondition for art.” To identify as simply Jewish would be to conform.

“It’s really important to not pigeonhole Shahn in any kind of ideological dogmatism,” said curator Laura Katzman, who debuted a version of the exhibition at the Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2023. “He really was someone who believed in freedom of expression, as long as it was presented in an ongoing way.”

Entering the gallery, visitors are confronted with the open coffins of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italian immigrants and anarchists sentenced to death for murder following a sham trial. The Sacco and Vanzetti series marked the development of Shahn’s early style and his theme of social justice. Informed by folk art and German Expressionists like Max Beckmann, he renders the scene with scuffed colors and severe tableau. Indifferent legal authorities, who deemed the trial fair, hold flowers, hovering over the peaked noses of the wronged men in their caskets.

But the series is at least the second time Shahn took up a cause celebre. When he was refining his line — which he first developed as an apprentice lithographer — Shahn did early studies of the wrongfully convicted Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus, what Katzman calls his “first engagement with social injustice.” (It isn’t included in the exhibition, she said, because of space and because the work is stylistically quite different from the rest of his oeuvre. But the subject tells us something.)

Shahn gradually moved beyond the particularism of antisemitism to a broader theme of persecution, though he intermittently revisited the plight of Jews. The image of Sacco and Vanzetti in their caskets seems to reappear in his mural for the Jersey Homesteads, a montage of Jewish immigration, with mothers or widows weeping over loved ones murdered in pogroms.

Shahn was born in Russian-controlled Lithuania in 1898 and had a typical Yeshiva education (his father, a woodcarver and a socialist, was exiled to Siberia and escaped to South Africa). Shahn stated that when he was around 6 he made a habit of approaching men in uniform and yelling “Down with the Czar!”

Shahn immigrated to the United States in 1906, growing up in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. As a young man in the 1920s he travelled through Europe, encountering its modern art — the Dreyfus studies come from this period — but he was dissatisfied emulating Matisse and others. He returned to America in time to document the Great Depression, and there developed his commitment to social realism.

Drawing from his own street photography and the work of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, their images visible in vitrines throughout the gallery, Shahn painted unemployed men waiting for work, striking miners and victims of the Dust Bowl. With the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Shahn became an ardent New Dealer, producing materials for the administration and its pro-labor agenda.

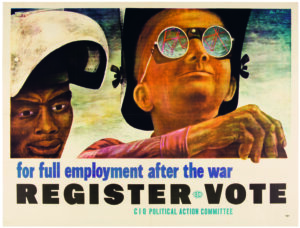

But even when he was working under the government, Shahn was quietly subversive, as in an image of two welders — one Black, one white — taken from a reference photograph in which both workers were white.

When America entered into World War II, Shahn began work in the Office of War Information, where he created a striking image of a man with a bag over his head, his torso emblazoned with the words “this is Nazi brutality,” referring to a 1942 massacre in Lidice. Shahn’s tenure at the OWI was brief — many of his designs were rejected for being too direct or startling — but antifascism remained a constant in his life, even as he redefined himself ideologically as a Social Democrat, Katzman said, leery of Harry S. Truman who was less committed to labor than his predecessor.

Following World War II, Shahn was immersed in the Cold War and became a target of McCarthyism. His work in the period, like that of the absurdists, grapples with how to make art in an atomic age. Abstract images, with interlinked dots signifying molecules — and perhaps the spheres of the kabbalistic tree of life — abound.

Holocausts of flame feature in his allegorical art and his series on the Lucky Dragon, a Japanese fishing boat whose workers were irradiated during a U.S. weapons test. At the time he also sketched Roy Cohn — his mouth open mid-tirade, recalling an earlier image of a contorted Father Coughlin — and J. Robert Oppenheimer, whose pitted eyes speak to his tragedy. (Shahn visited Oppenheimer in Princeton to draw him from life.)

In the last decade of his life, Shahn produced a Time magazine image of Martin Luther King, which, as a woodcut print in the gallery’s space devoted to civil rights, is marked with a red, square stamp in one corner. The stamp is the jumbled Hebrew alphabet, an insignia he had made in Japan in 1960.

The red chop stamp, a nod to the Alphabet of Creation, Shahn’s retelling of a story in the Zohar, merges with subjects that would appear to have little to do with Jewishness. And yet, as the final stretch of the exhibition shows, his complicated engagement with Judaism was always a feature of the work, in ways both obvious and oblique.

Shahn produced Jewish art throughout his life, including a Haggadah, an illuminated text of Ecclesiastes and a number of works inspired by the Book of Job and God’s seeming indifference to his suffering.

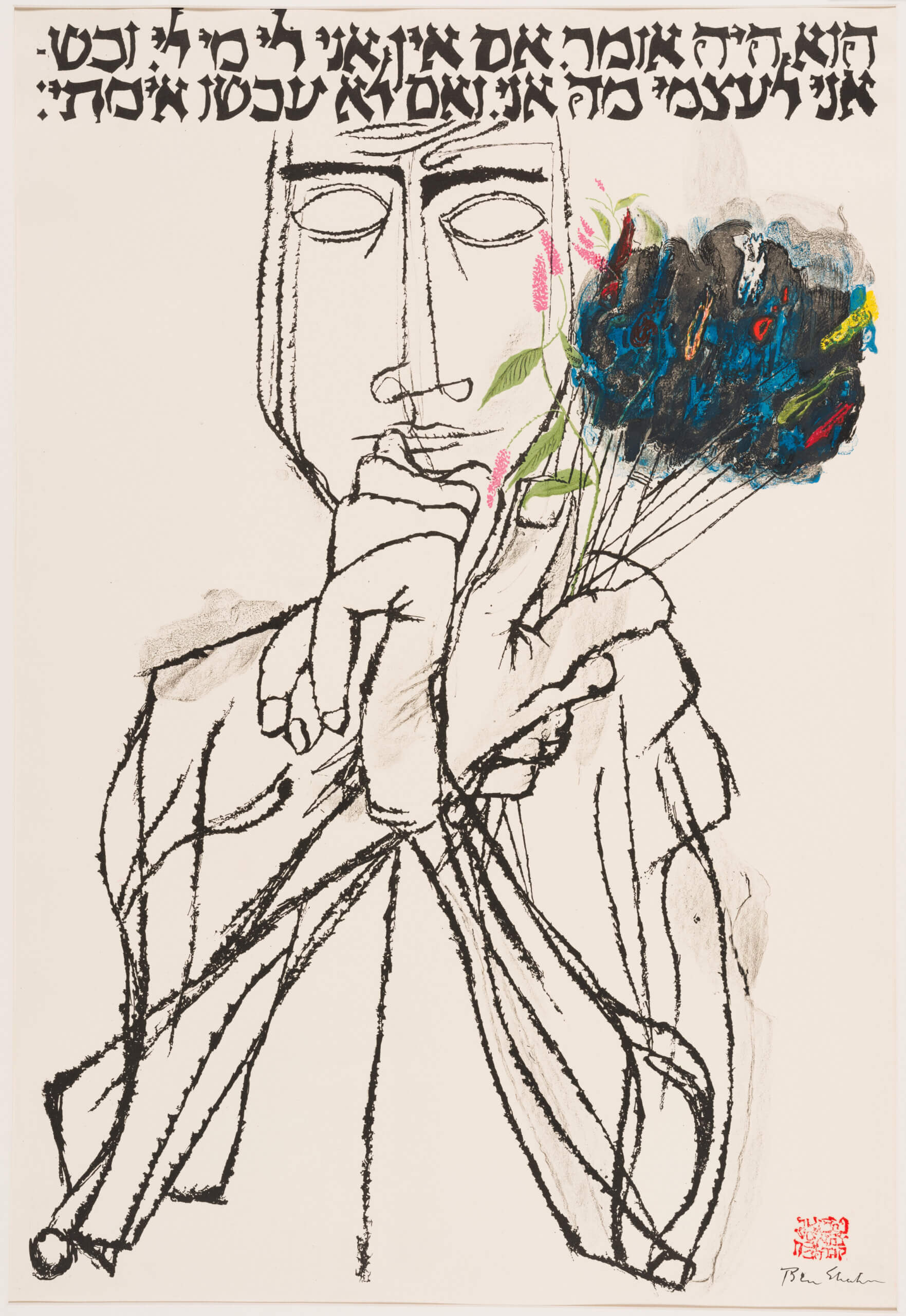

The final image in the gallery, Flowering Brushes shows a figure grasping a bouquet of paintbrushes, a hand by his chin, in a pose recycled from a reference photo of a farmer, also in a rendering of a man in a concentration camp. Above the figure, considering his purpose or his canvas before an act of creation, is the famous quote of Hillel in Hebrew: “If I am not for myself, who is for me? If I care only for myself, what am I? If not now, when?”

In this image and these words, we see how Shahn assimilated a worldview. If it refused to conform, it was nonetheless consistent.

Correction: A previous version of this article misattributed Shahn’s saying “Down with the Tsar” as a child. The memory originated in a 1968 oral history, not Diana L. Linden’s book Ben Shahn’s New Deal Murals: Jewish Identity in the American Scene.

The exhibition Ben Shahn, On Noncomformity runs May 23 through Oct. 12 at the Jewish Museum in New York.