How Martin Buber Lost Friends and Irritated People by Being a Happy Jew

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

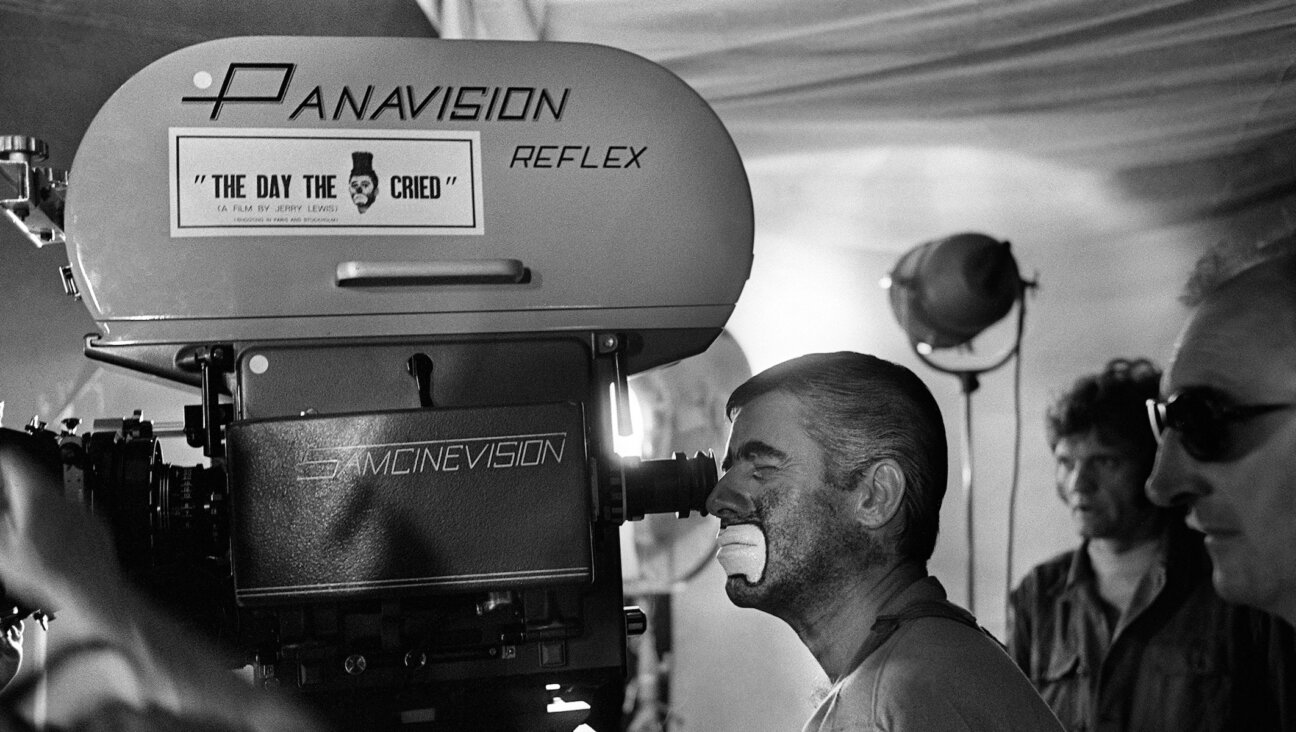

Image by Wikimedia Commons

Fifty years after his death in Jerusalem in 1965, Martin Buber, the Austrian-born Israeli Jewish philosopher has “left an ambiguous impression,” as Walter Benjamin wrote to Gershom Scholem in 1936 about Buber’s appearance at a French philosophical gathering. Buber’s “I and Thou” about human relationships to people and things, is famously cited in Martin Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” as an argument against segregation. Buber’s popularization of Hasidic legends and translation of the Bible into German in collaboration with Franz Rosenzweig are celebrated, although not by everyone. Buber remains controversial, as “Martin Buber: Humanity’s Sentinel,” a new biography from Albin Michel publishers, establishes. Its author is Dominique Bourel, who has written about Max Nordau, Moses Mendelssohn, and other subjects. Recently, while on a visit to Jerusalem, Professor Bourel spoke to “The Forward’s” Benjamin Ivry about the ongoing disputes over Buber’s legacy.

Benjamin Ivry: Why were so many writers divided between respect and contempt for Buber? Walter Kaufmann, translator of “I and Thou,” compared its style to Khalil Gibran’s “Prophet,” with “inauthenticity… a pose without any redeeming wit or irony. It approximates the oracular tone of false prophets.” Was Kaufmann right?

Dominique Bourel: No, of course I think not, but Buber is often between two fields. He writes too well to be a philosopher, and that unsettled people. Buber wrote many poems, and he is just being discovered as a man of letters. This is what impressed [the songwriter] Leonard Cohen, and many other writers who appreciate him as a great prose writer rather than as a philosopher. Kaufmann and all his generation endured a great deal of pressure from existentialism and structuralism and this interfered with their appreciation of Buber. Recently, Buber was retranslated into Hebrew because the older translations were very “Yekke,” [German-speaking Jewish], very 1950s and stately, and this too will change the perception of Buber.

In 1918 Franz Kafka wrote to Max Brod that Buber’s most recent books were “revolting, repulsive” and that his “Tales of Rabbi Nachman” and “The Legend of the Baal-Shem” were “insufferable.” Kafka accused Buber’s writings of being “lukewarm.” Why?

I think Kafka was disappointed that Buber was not revolutionary enough, that he did not make a real revolution in the heart of Jewish culture, using the Hasidic stories as a kind of bomb to break up the tradition of salon literature. Kafka’s “Letter to the Father” expressed a radical view of literature, not at all in the style of Buber. Kafka may have found that Buber did not really pay tribute to the depth of Jewish tradition.

In his memoirs, Gershom Scholem stated that in person, but not always in lectures, Buber could be impressive, yet some of his writings had an affected tone which did not ring true.

I do not agree at all. Buber was a magician with words. Towards the end of his life, Scholem told me that Buber was so essential that he changed the lives of many generations. [Scholem] was a bit annoyed that his criticisms of Buber had been remembered as much as they were.

Scholem, among others, noted that Buber’s Hasidim were unlike historical or current Hasidim. In 1966, Scholem added that Buber’s “language was infinitely colored, poetic, rich in evocative images and at the same time curiously vague and impenetrable.”

Buber’s works were a form of introduction. The great professor Scholem wrote some texts which were quite boring, while Buber’s texts were attractive even for non-Jewish readers. The German language is fascinating because one often doesn’t know the exact meaning of words. Scholem wrote in a dry and very precise way, and he was perturbed by [Buber’s] writing.

The philosopher Leo Strauss believed that Buber, whom he saw as inauthentic and artificial, was victim of a “radical lack of clarity.” He called Buber merely a “seller of perfumes.” Why so?

Leo Strauss knew Buber quite well, and Buber’s beard always smelled good; people used to joke about it even with him. His eau de toilette attracted humorous comments. Strauss took each text to mean the opposite of what it seemed to mean, or that we must read between the lines. The idea is not to be charmed immediately by the sentence, but to make sure it is logical. That is light years away from Buber, who was raised in the tradition of [authors Stefan] Zweig and [Arthur] Schnitzler.

“Martin Buber: Humanity’s Sentinel” quotes the German Jewish philosopher Edmund Husserl who claimed that Buber “doesn’t exist, Buber is a legend!”

He meant that Buber was already very, very famous. That annoyed Husserl, just as it irked Scholem. Buber was much involved with the media and gave many lectures, and someone as reticent as Husserl was being a bit ironic about that. Husserl never really came to terms with his own Judaism and that may also have played a role.

In an essay, the Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz called Buber a “thinker of great banality, third-rate… I see him as a Jew who loathed Judaism, who deformed and falsified Hasidism, and aspired to Christianity.”

You know Leibowitz often wrote one-liners like an eagle jumping on its prey. The fact that Buber was not observant may have been a problem. Buber was seen as the most eminent exponent of Judaism, and others did not like that. To say that [Buber] loathed Judaism is foolishness. Buber earned lots of money from his books, and in universities there are always jealousies.

Theodor Adorno wrote that Buber was a “Tyrolean of religion.” Did that imply philosophy like a superficially pretty tourist landscape? Or was it also another criticism of Buber’s writing style?

Absolutely, that is exactly right. Adorno was among the nastiest of all these critics. I think this is indeed also a stylistic criticism.

You note that the poet Paul Celan sent Buber’s “Tales of Rabbi Nachman” to all his romantic conquests. Is there a seductive power in Buber, a kind of intoxicating romanticism? Scholem referred to wild admirers of Buber as passing through “buberty,” a rather facile jest, it must be said.

Yes, of course. Like all seductions, some one-time admirers of Buber may have behaved later like disappointed lovers. At first they were infatuated and then almost regretted having been taken in. The seduction of the shimmering language was because Buber was at the confluence of several styles of language. His knowledge of the Bible was so thorough that he had at least 35 registers of language at his disposal. Just as the Bible was meant to be read aloud, Buber’s letters are performance texts waiting to be read aloud onstage.

*In a letter from 1936, Walter Benjamin wrote to Scholem about his “mistrust” of Buber, who he claimed was guilty of “transposing the terminology of National Socialism into debates about Jewish questions.”

[Cultural critic] Siegfried Kracauer also said Buber’s translation of the Bible was Wagnerian and reactionary. Benjamin was a tragic character whose life was a constant struggle. When people enjoy a destiny like Buber, succeeding in many things, people whose lives are different may find little in common with them.

The philosopher Marc de Launay has termed Buber’s translation of the Bible as the “unsurpassed expression of Jewish creativity in a German context.” Was it Buber’s greatest book?

That’s a very, very good question because it’s still debated. [The translation] is very much read in Germany, and some do not understand the way it wrestles with language, so that the reader hears the Hebrew while reading German. Buber was one of the first to say that the Bible should be spoken and heard.

You assert that Buber, like Moses Mendelssohn, shows that the history of Jews and Judaism is not just an account of anti-Semitism, but that there were also happy Jews, sometimes more often in Germany than elsewhere. Did some critics attack Buber because of his happiness?

Yes, absolutely, you are perfectly right. I always say I do research on happy Jews and my colleagues ask, ‘How can you find one?’ Even some survivors of concentration camps can be happy. Instead of writing so many books on anti-Semitism, why not send out another message, rather than one of tragedy? In Israel today, there are many happy Jews. They are here where they chose to be, they are comfortable in their own skins. People who write about anti-Semitism think they will convince anti-Semites by analyzing how their thinking works, as if books could convince lunatics. In my opinion, Buber was a happy Jew, and that irritated people, too.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.