In a time of xenophobia, displacement and distraction, we need Homer’s ‘Odyssey’ more than ever

Informed by scholarship and family history, Daniel Mendelsohn’s translation is both vital and timely

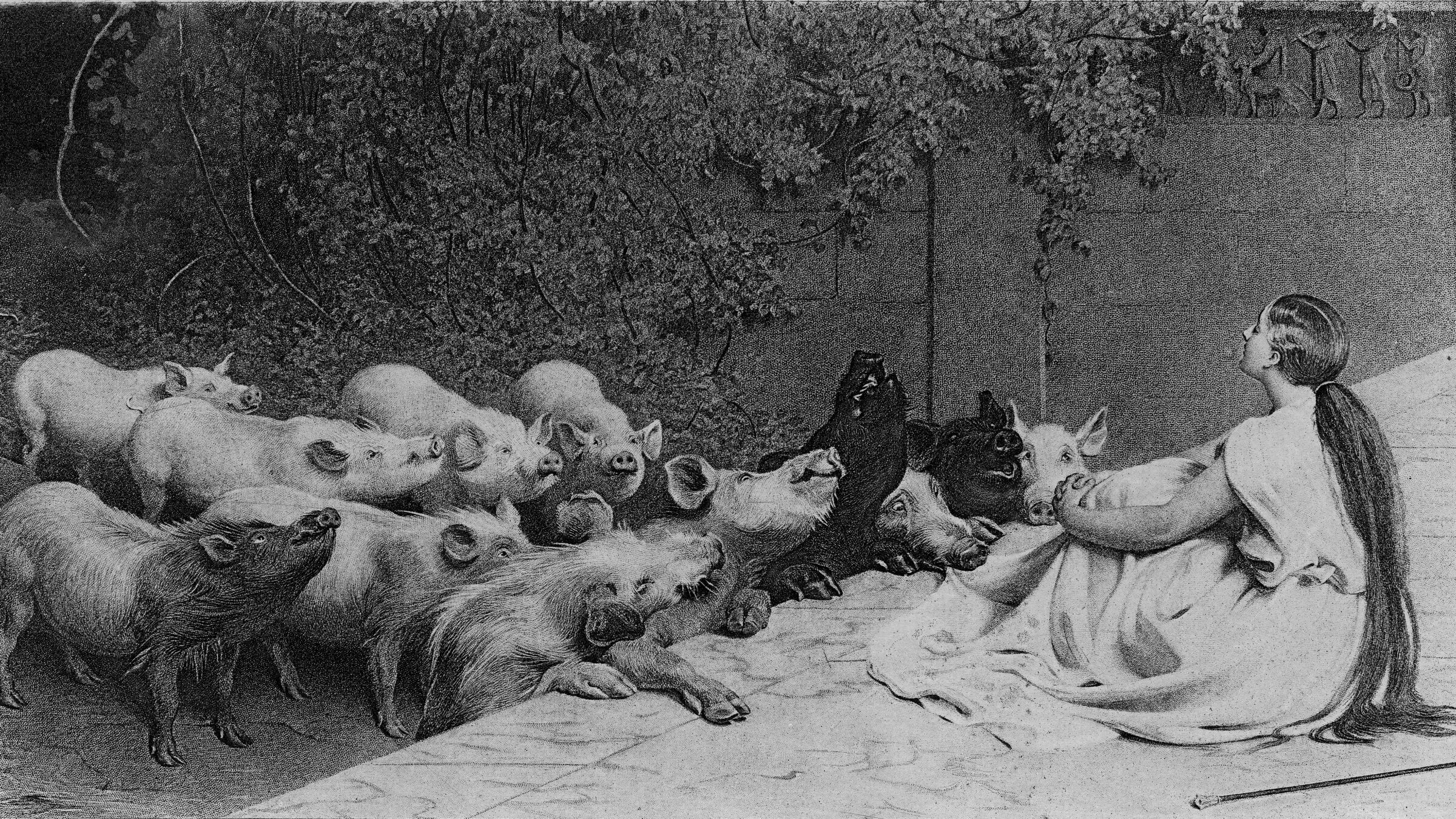

Circe sits before the Companies of Odysseus after having turned them into a herd of swine on the Island of Acaca. Photo by Getty Images

It’s often said that “Every generation needs a new translation.” Less often asked, however, is whether this claim is actually true. Does each generation, after all, really need a new translation? After all, despite the dozens of subsequent English translations of the Bible into English, the King James version, though 400 years old, remains the standard by which all others have since been compared.

This question comes to mind with a spate of recent translations of Homer’s Odyssey. Over just the past eight years — one third of a single generation — those who cannot read Greek can choose among Emily Wilson’s 2017 version; Peter Green’s 2019 account; and most recently the 2025 rendering by Daniel Mendelsohn.

It happens that Greek is one of the several hundred languages I cannot read. Yet, it also happens that I have read and taught various translations of the Odyssey — including those by Robert Fitzgerald, Robert Fagles and Stanley Lombardo — far longer than it took Odysseus to sail from and back to Ithaka.

Unable to judge the fidelity of these translations to the original text, I tend to measure their ability to speak to my students. When I first started teaching in the late 1980s, my students found the Odyssey strange and challenging, but they were primed to read the book. Forty years later, this is less the case with students besieged by an online army that seeks to colonize their attention.

As a result, my students now tend to approach the epic less as a marathon and more as a death march. Given the advance sales for Christopher Nolan’s adaptation of the Odyssey, which will not be released until 2026, we are reminded that we might be returning to the oral culture of Homer. Rather than gathering around a fire to watch and listen to a bard sing the story of wily Odysseus, we instead gather around screens large and small to watch and listen to Matt Damon in that very same role.

This might explain why many of my students find Wilson’s translation more gripping — or, at least, less of a slog — than the older versions. Rather than using what she calls the “mild stylistic archaism” of earlier translations, Wilson instead tries to write in “the rhythms and phrases of contemporary anglophone speech.” Her style is snappy, not slangy, less concerned with plangency than with clarity, achieved by great rigor, skill and knowledge.

Does this, though, at times come at a cost? The brilliant essayist and critic Daniel Mendelsohn thinks so. In his introduction, he discusses several earlier translations, but gives special attention to Wilson’s version. He suggests that Wilson’s focus on brevity necessarily scants the texture and subtlety of the original text (an epic whose telling, it must be noted, varied from one performance to the next until it was finally inscribed on parchment sometime in the 7th century B.C.E.). Noting the differences between their approaches in a few examples, Mendelsohn concludes that while Wilson’s approach “might make it feel approachably modern for some readers, especially young ones … it is worth remembering that Homer never felt ‘modern,’ even in his own time.”

I have no scholarly standing in his debate, but I am intrigued by the differences in a passage that Mendelsohn does not cite in his introduction. It is one that reflects two concepts, nostalgia and hospitality, that are at the core not just of Homer’s poem, but also of human history. It occurs in Book Five, when the reader first meets Odysseus, who is being kept by the lovesick nymph Kalyspo on her island. Ordered by Hermes to release Odysseus, Kalypso reluctantly goes where she knows he will be. In her translation, Wilson reports, Odysseus sat “out on a rocky beach, in tears and grief/staring in heartbreak at the fruitless sea.”

In Mendelsohn’s version, Kalypso finds Odysseus on the beach, but it is a scene depicted with great nuance and detail: He is sitting “on the rocks by the edge of the sea/Weeping and moaning and tearing his heart to shreds in despair/The tears pouring down as he stared at the restless wastes of the sea.” Whereas Wilson’s lines are swift and spare, Mendelsohn’s are prolonged and attentive. He pauses because Odysseus’ plight demands that we pause; we need to pay attention to the condition that has befallen not just Homer, but will befall most all of us sooner or later.

In both Wilson’s and Mendelsohn’s versions, nostos — the painful longing for a past time and home that we call “nostalgia” — resides at the heart of this epic. So, too, does xenos, which means, oddly and tellingly, both guest and stranger. It is the word that gives us both the familiar word “xenophobia,” which means fear of the stranger, as well as the unfamiliar “xenophilia,” or love of the stranger.

Odysseus is, by turns, the stranger and the guest, who is driven by nostalgia over the course of his story; he is received unreservedly by some, rejected unreservedly by others. Clearly, this condition as both a guest and a stranger is not limited to Odysseus, but is the lot of countless others over the millennia who, through circumstances beyond their control, have been torn from their homes and find themselves strangers in strange lands, longing for what they loved and lost.

Wilson movingly addresses this condition in the final paragraph of her translator’s note, where, in her words, she asks us to imagine a stranger outside our house, a stranger who is old and ragged and tired, wandering for years and whose name you do not know. And you invite him inside your home. “He may remind you of your husband, your father, or yourself … Let him eat and drink until he is satisfied. Be patient. When he is finished, he will tell his story. Listen carefully. It may not be as you expect.”

It is this same theme that Mendelsohn had already addressed in his earlier books An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic and The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million. The first is his often-moving (and frequently funny) account of a trip he made to Greece with his father who had attended his class on Homer and with whom the son had deep but difficult ties. The second book is an account of Mendelsohn’s effort, spurred by a longing to discover a family and a home — in a word, to find himself — obliterated in the Holocaust.

This same concern and connection with the human condition, one informed by nostos and xenos, infuses Mendelsohn’s translation of Homer’s epic. In his introduction, he devotes several pages to these themes, arguing that the importance of xenia is paramount for Homer and that it is an ethical imperative that keeps surging to the surface of events.

Perhaps the most dramatic instance of this is when Odysseus, who has returned to Ithaka and is disguised as a beggar, is humiliated by Antinoos, the obnoxious leader of the army of suitors demanding the hand (and property) of Penelope. Another suitor lambastes Antinoos for his behavior, reminding him that “the gods often take the appearance of strangers from far-off lands/Assuming all sorts of guises as they wander around our cities/Observing the deeds of mortals, whether insolent or righteous.” Soon enough, Antinoos and the other suitors realize too late — the tragic moment the Greeks called anagnorisis, or recognition — the truth of that warning.

Homer was not, of course, concerned with political movements or ideological currents, economic competition or climate change, all of which have contributed massively to the growth of displaced persons and desperate refugees. But, as both Mendelsohn’s and Wilson’s transitions make clear, Homer’s tale is no less timely than it is timeless. Reading the Odyssey today reminds us that the moment of recognition will always occur for individuals as well as nations. While the gods may no longer walk the earth, the code of ethics these divine beings embodied remain very much with us.