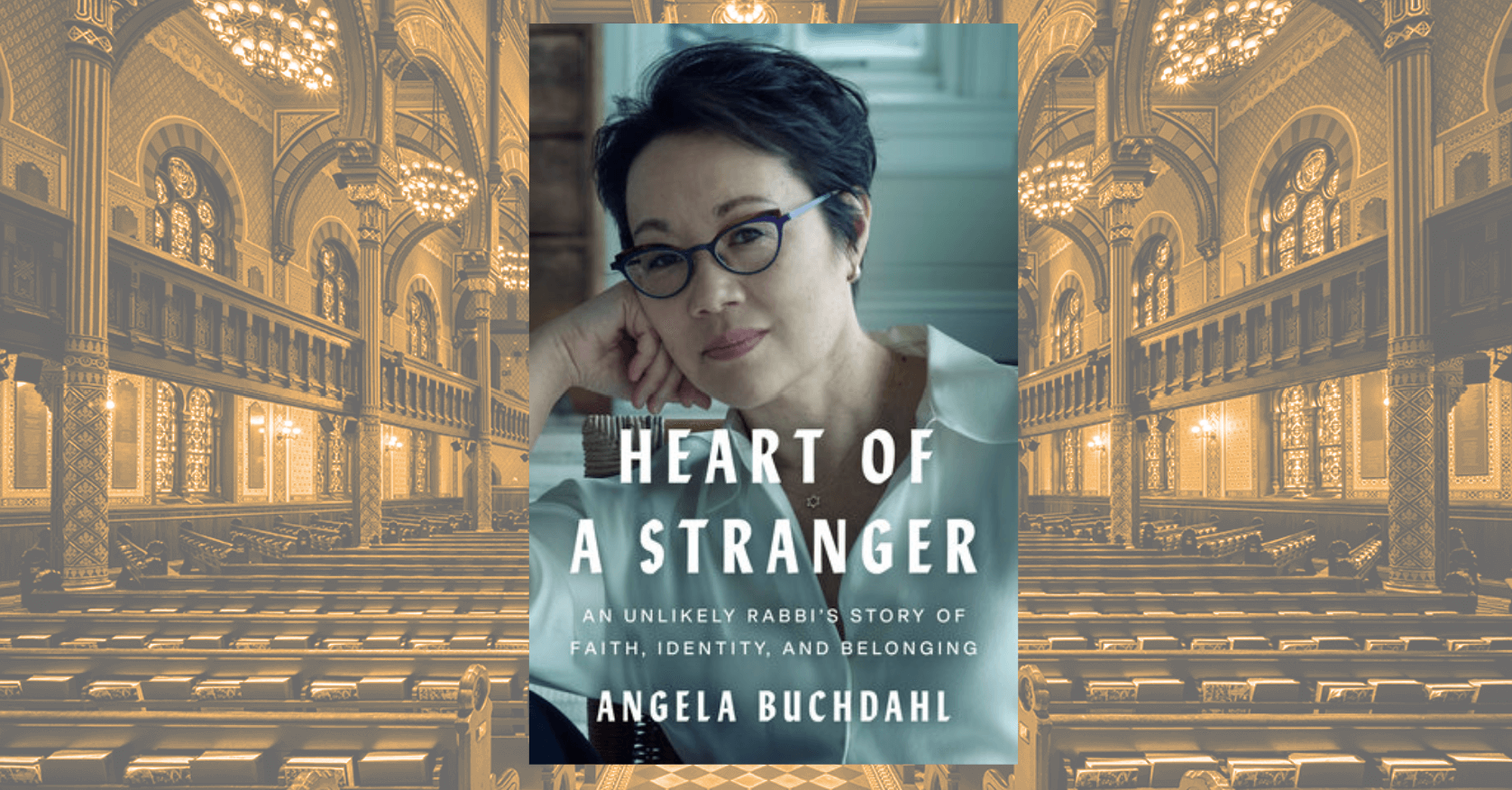

How an ‘unlikely rabbi’ went from Korea to Colbert

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl’s memoir ‘Heart of a Stranger’ charts her journey as the first Asian American rabbi and cantor

Rabbi Buchdahl’s memoir, Heart of a Stranger, takes its title from the Torah. Courtesy of Penguin Random House; Central Synagogue

Calling herself an “unlikely rabbi,” Angela Buchdahl has been a staple on numerous lists of notable American Jews, including the Forward 50. Born in South Korea in 1972 and raised by a Korean Buddhist mother and an Ashkenazi Jewish father in Tacoma, Washington, she went on to become the first Asian American ordained as a rabbi and first as a cantor. Today, she leads Central Synagogue in New York City, one of the largest and most influential congregations in the country.

Her new memoir, Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging, traces that journey, from the embracing Jewish community she grew up in to finding herself the answer to a Jeopardy question (“What is rabbi?”) — and, even more bizarrely, picking up the phone one day to hear a hostage-taking gunman make demands of her as the “chief rabbi of the United States.” In advance of the book’s release and a launch event hosted by Stephen Colbert, I spoke with her about claiming her place in Jewish life and the responsibility of Jews to always think of the stranger as themselves.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How did you nab Stephen Colbert for your book launch event — or did he nab you?

His son and my son were college roommates, and I got to know him and his wife, Evie. I learned quickly that this was not only a very funny man and a very good interviewer, but someone who was deeply faithful. He teaches in his church and thinks a lot about faith. I’m very grateful that he said yes.

Your title is Heart of a Stranger. I want to challenge you on that: Haven’t you and I worked for years on representing Jews of color as normative? Are you still feeling like a stranger?

I guess I would argue that you never fully let it go. It’s like someone who says they were chubby as a kid. They’re not chubby anymore, but there’s some way in which they always see themselves as the chubby kid. You carry certain formative identity markers from childhood into your adulthood.

Heart of a Stranger is not an original title. I took it from Torah, which says, “Do not oppress the stranger. You know the heart of a stranger. You were strangers in Egypt.” This is the existential state that Jews are supposed to understand and know. The danger is when we get too comfortable, too powerful, too complacent.

Along those lines, you write about undergoing a conversion, even though your family was Reform, which by the time you were growing up had recognized patrilineal descent. That brought to mind Julius Lester’s conversion, which actually was something of a reversion because his great-grandfather was a German Jew. Lester said that he wasn’t converting to be accepted; he was converting for himself, saying, “I would do it even if no Jew ever accepted me.”

I had a very similar experience. I rejected the idea of converting when it was first suggested to me at age 16. Growing up in Tacoma in a Reform synagogue in my little Jewish bubble, I was accepted without a lot of questions. But I had a lot of existential identity questions: “Was I Jewish enough? Was I authentic enough? Was I learned enough?” And some of the answers were not yes.

I termed it a reaffirmation ceremony rather than conversion, because conversion sounds like turning into something that you weren’t before. I recognized that with a beit din of three Reform rabbis, it wasn’t going to change my status one whit for an Orthodox Jew. But it wasn’t for them. It was really a way to ritually mark the journey that I had been on and the acceptance of my identity in a way that felt important to me.

One reason I live in Duluth, Minnesota, is I’ve called our little Temple Israel here the warmest shul that I’ve ever found in one of the coldest places on earth. Do you find it true that smaller Jewish communities are more embracing than large ones?

I grew up in a small community that was incredibly embracing of my family, including my mother, and that made a huge difference. I now work at a very large synagogue. I think the big difference is when you’re in a community where not everybody knows each other and they’re encountering people who are strangers. That’s when the inevitable questions come up.

It was disappointing for me after many years of being the senior rabbi of Central to hear from Jews of color who said Central wasn’t as welcoming of them as I thought. It hadn’t solved every problem just by having me as the senior rabbi. That was a painful realization that started a conversation that has shifted the culture at Central.

You write about the synagogue takeover in Colleyville, Texas, in 2022. The perpetrator who held the rabbi and congregants hostage called you while it was going on. He seemed to think that you were the “chief rabbi of the United States.” On the one hand, you’re balancing this misperception of your influence and power. On the other, this was a real situation of life and death.

That was one of the most surreal and destabilizing experiences I’ve ever had as a rabbi. They don’t train you for hostage negotiation in rabbinical school.

This terrorist clearly had done a lot of research. He researched the synagogue, which was the closest synagogue to the federal prison from which he wanted a prisoner released. The FBI went through his computer and saw that he was searching for what he thought was the equivalent of a chief rabbi because he was from England, where there is a chief rabbi. Of course, that doesn’t exist in America. He also mentioned that he saw pictures of me with President Obama at the White House. I think given Central’s name, and the fact that I had been the answer to a Jeopardy question not long before, may have put me higher up on the search algorithm.

It was terrifying because I felt that he very explicitly put the lives of these four people on me. And yet, I felt powerless to do anything. This is a case where I realized the danger of the antisemitic trope that he had imbibed since childhood, that Jews control the government and can make a few phone calls and get anything done. When I said to him, “I don’t think I have as much power as you think I do,” he was like, “Of course you do.” So, yeah, it was a terrifying day. I continue to give thanks that the four who were being held hostage survived.

Another weird note is that he seemed to think it normative that a Jew of color would be the chief rabbi of the United States. Does this mean our efforts for a more inclusive representation of Judaism are paying off?

It is funny because when I was named senior rabbi of Central, there was an Orthodox publication that had a headline like, “It’s official: Non-Jews can be rabbis” — literally calling me a non-Jew. And here was this deranged gunman who seemed to think I was the chief rabbi. I can laugh about it in some ways now that it’s over, but it is ironic.