Nudniks, nude performers and a Nobel winner have one thing in common — they all love the Marx Brothers

The second ever Marxfest drew visitors from across the country to celebrate the beloved family act

Marxfest brought visitors from far and wide to celebrate the legacy of four brothers from New York. Courtesy of Marxfest

The Marx Brothers helped Paul Kane’s immigrant mother learn English. They bonded Tom Motley with his daughters. At 11-years-old, Keaton Harper learned to play the harp to emulate Harpo Marx — and survived college during the pandemic by asking “What would Harpo do?”

In a packed two weekends in May, these stories emerged at Marxfest, a celebration of Groucho, Harpo, Chico and sometimes Zeppo. The festival, which boasted over two dozen events, is the second installment of an endeavor that began a decade ago and was timed for the centennial anniversary of the Marxes’ debut on Broadway in the 1924 musical I’ll Say She Is.

Just under 1,000 tickets were sold for the six-day extravaganza in midtown Manhattan and Coney Island, with devotees coming on the subway from their apartments uptown, driving in from Boston or Philadelphia or flying over from Minnesota, Florida, North Carolina and California. Attendees and panelists included the onetime mayor of a New Jersey township, leading critics and Marx scholars, an attorney for a Nobel Peace Prize-winning coalition to abolish nuclear weapons (who moonlights as a Harpo impersonator) and even Groucho’s grandson Andy Marx.

“Marx Brothers fans are the most wonderful people in the world, and it’s been a long time since we’ve gotten a lot of us in one room together,” said Noah Diamond, a member of the Marxfest Committee and cohost of the Marx Brothers Council podcast, which has a vibrant Facebook community.

”It’s almost like a family reunion,” Diamond said, while a convocation of enthusiasts milled around the solarium of the 3 West Club on West 51st Street in Manhattan.

Family history was a major theme. On the first evening, Moss Hart’s son, Christopher, shared his parents’ relationship with the brothers and Groucho’s sound archivist John Tefteller excavated rare audio from radio programs and live appearances. Fans were brought to the edge of tears when they heard Harpo, at a benefit concert for the Riverside Symphony in California, break his silence to introduce the instruments in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf.

“I was crying with the Harpo recording,” said Brad Sohlo, 62, from Minneapolis, making his first trip to New York for the festivities. “There was a lot of nuance to his voice. He sounds like Chico.”

“It makes sense,” said Carl Bergmanson, clad in a top hat and purple sequined jacket. “They’re close in age, they look very much alike.”

Sohlo noted how Chico and Harpo used to double for each other onstage. Often, Chico would book a piano-playing gig and, bailing to pursue a woman (he was named “Chico” because he chased the chicks), have Harpo sub in for him, only for Chico to return when the set was over to take the money.

“Can you tell we’ve been reading about this a long time?” Sohlo asked me.

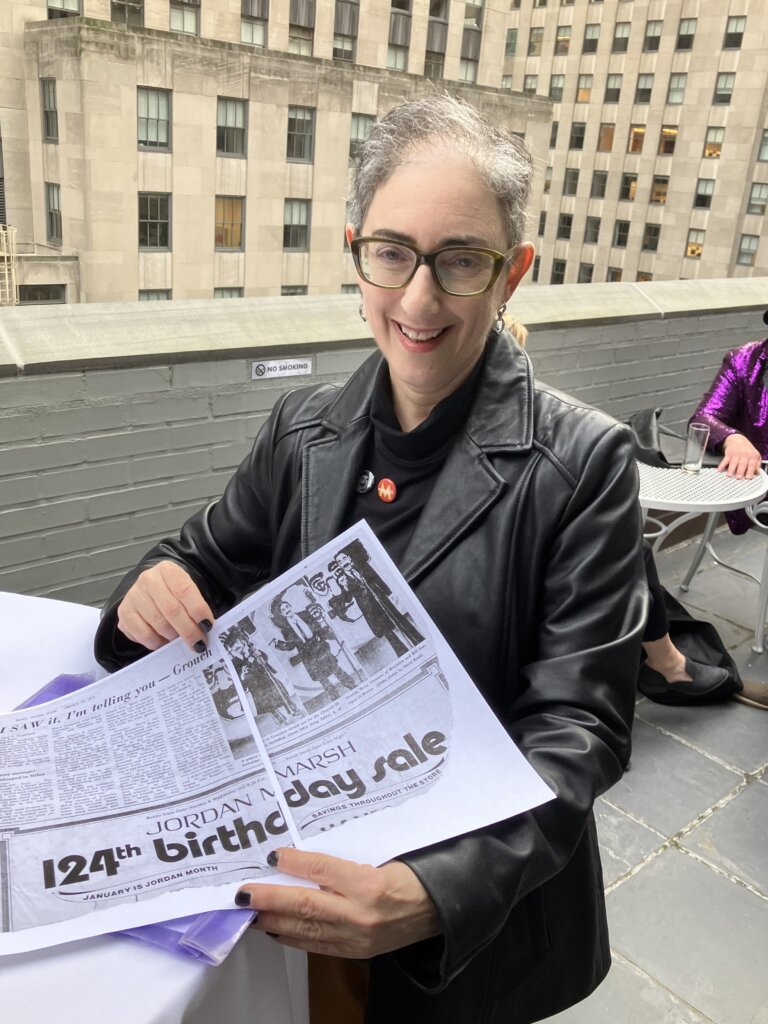

At the opening night party, Betsy Sherman, 67, there with her brother, was eager to show me a photocopy of an article that showed her in a Groucho lookalike contest in Jan. 1975.

“I didn’t win, but I got my picture in the Boston Globe,” Sherman said.

A 4-year-old child could understand this — go out and find me a 4-year-old child

Born Leonard (Chico), Adolph (Harpo), Julius (Groucho), Milton (the enigmatic Gummo, who sold raincoats instead of starring in movies) and Herbert (Zeppo), in that order, the brothers were all products of the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan. They grew up performing together in vaudeville and were third generation entertainers on their mother, Minnie’s side. They starred in 13 films.

In gaps between presentations about the Marx brood’s astrological birth charts, walking tours of their theatrical haunts and sites of interest for the Algonquin Round Table, where Harpo was a habitué, Marx fanatics offered their ranking of the movies (most hate Go West). They quoted Groucho’s quips and exchanged trivia. Though nothing was barred for casual fans, everyone knew the secret password: swordfish.

Many of the attendees were baby boomers who witnessed the Marx Brothers revival in the 1960s and ‘70s, when the films would play on television and often in cinemas. Groucho, who died in 1977, became a counterculture icon in his later years, adorning dorm rooms and literally playing God in the hippie satire Skidoo. Comedian Gabe Kaplan, who brought high profile Marx impressions to primetime in his sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter, spoke to a packed crowd in his native Brooklyn via Zoom, a living link between the brothers and those who came of age during the era of Battle of the Network Stars.

But throughout the two weekends of Marxfest, there was anxiety about the Marxes continuing to appeal to the next generation.

Trav S.D., one of the organizers and the author of Marx Brothers Miscellany, ended his presentation on the Marxes, vaudeville and silent film with a call to spread the good word of the madcap brothers.

“My mission for you all is to find ways to talk to young people, because they’re increasingly resistant to vintage entertainment of the kind we like,” S.D. said. “ If you don’t,” he warned, “the Marx Brothers may soon be as dead as Larry Semon,” Who’s Larry Semon? Exactly.

Who are we to believe about this crisis of Marx continuity — him or our lying eyes?

Courtney Chess, 31, who came in from Philadelphia with her husband, Trent Austin, 30, and attended Noah Diamond’s presentation about I’ll Say She Is, said she grew up watching Turner Classic Movies and introduced herself to the brothers.

“When I saw A Night at the Opera and the orchestra scene, I was like, ‘Yes.’ And then I needed to know everything,” Chess said.

Still, while she was chatting about favorite movies and bits, Chess revealed a possibly generational schism.

She said that, as a domestic abuse counselor, she was disappointed that comedian Robert Klein, in a conversation with Jason Zinoman about the Marxes’ influence, appeared to cast doubt on Dylan Farrow’s sexual abuse allegations against Woody Allen. Chess was similarly disappointed with a Marx Brothers cartoon featuring racist minstrel characters, which was presented without a disclaimer or context.

When Duck Soup screened at the United Palace in Washington Heights, to a more diverse crowd of 435 people, Groucho’s reference to the song “That’s Why Darkies Were Born,” drew an audible groan.

But this observer also saw signs of generational transmission. Jared Blank, 55, said he’d watched Animal Crackers about 50 times with his kids (skipping over the “boring parts,” i.e. anything without the brothers). One elementary school-aged child, sporting Groucho glasses, attended Duck Soup with his father.

Tom Motley, a cartooning teacher seen sketching throughout the talks from the audience, said his father introduced the neighborhood kids to the Marxes in the 1960s, when Horse Feathers and Duck Soup played as a double feature. He’s since shared the films with his daughters and had a chance to see a version of the brothers live when Diamond revived I’ll Say She Is off-Broadway.

I saw more than a few parents with their kids, including my old friend Charles Nechamkin (we didn’t plan it) who went with his mother on the Saturday morning walking tour tracking the mostly-demolished venues where the Marxes performed in their stage days. The L’dor V’dor was strong, even if the very young weren’t present for the talks, which, I imagine, would seem a bit too much like school for their enjoyment.

Cinco Paul, co-creator and co-writer for the Despicable Me movies, attended the festival as a fan, and, one trusts, he may be smuggling a Marxian sensibility into his children’s films, possibly in those mischievous Minions.

One thing a casual fan of any age, there to hear stories of Groucho’s bon mots or even the life story of regular Marx player Margaret Dumont, might not anticipate is that the Marxes could still be cool, and even sexy through, well, sex.

A Marx Brothers burlesque

Marxfest’s second night topped off with a dinner theater revue where an emcee was briefly topless.

Jonny Porkpie, one of the Marxfest organizers, revealed his bare torso after a mostly wholesome evening featuring songs from the films and the unforgettable silverware dump by Harpo impersonator Seth Shelden, the one who’s a lawyer and United Nations liaison for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

Porkpie, who once ran for mayor of New York, is a burlesque maven who wrote and starred as Groucho in a performance he called “A Day at the Boardwalk, A Night at the Strip Show,” which was inspired by a 1939 order from urban planner and all-around killjoy Robert Moses to ban “ballyhoo” from Coney Island, including burlesque.

A parody of “Moses Supposes,” from Singin’ in the Rain tunefully argues that his plans will be foiled, as “shows without clothes is what folks wanna see.”

The audience for the show, which started at 9 P.M., was notably younger than the one for the Marx symposia, but the performance checked off the familiar Marx boxes incorporating wordplay, clown and musical numbers between the pasties and g-strings.

Porkpie, who helped arrange the Coney Island weekend, also encouraged the inclusion of a panel about the Marx Brothers and Jewish identity.

“It’s so in their DNA,” said Porkpie, who is himself Jewish. “In a way, it’s why I connect to them. They’re such Jews. Even a Chico! He’s talkin’ a Jewish.”

The heirs to Sholem Aleichem, or just good friends of Sid Perelman?

The Marxes are cornerstones of American Yiddishkeit — but they didn’t speak Yiddish.

“No other American performers have inspired such wide-ranging speculation as to the Jewish origins of their art,” said film scholar and critic J. Hoberman, who was part of the Jewish identity panel with Noah Diamond and author Danny Fingeroth. This interest in the quartet’s chosenness persists despite the fact that the Marxes made very few explicitly Jewish references in their films, and the ones they did make may have come from the pen of George S. Kaufman or S.J. Perelman.

What makes the Marxes, who came not from the Yiddish theater on Second Avenue, but the anglophone stages of vaudeville, such Jews? It may well be in the eye of the beholder, and certainly not in the eyes of the Marxes themselves.

“Described by one critic as the ‘symbolic embodiment of all persecuted Jews for 2000 years,’ Groucho was said to have responded, ‘What sort of goddamn review is that?’” Hoberman related.

Hoberman said that the Marxes were from a German Jewish tradition of traveling family acts dating back to the Middle Ages. For a time they slipped into the ethnic stock type of “Hebrew,” with Gummo playing a Jewish school boy in a stage routine, but as Diamond said, that was just one characterization in their arsenal. Before Harpo developed his mime persona, he played Irish. Chico, as we know, played Italian.

And so critics, one of whom said the brothers Marx picked up the mantle Sholem Aleichem, may well have been projecting. Still, the Jewish constituency has always been a vocal segment of their fanbase, showing up in force at Marxfest and, predictably, laughing at the comparison.

The tricky business of Tikkun Olam

The festival’s final event, a “Harpo Summit,” connected the least loquacious, but most expressive Marx to a broader heritage, one at once universal and quintessentially Jewish, making the brothers, and their fans, mishpocheh beyond a doubt.

Scholar Charlene Fix, appearing alongside actors who’ve portrayed Harpo, argued that the mute Marx fits the ancient archetype of trickster.

Tricksters tend to emerge “during cultural and historical moments that call for healing, cleansing and corrective chaos. They’re unpredictable and disruptive. They push against humanity’s potential to turn against itself by taking on power, complacency, rigidity, injustice, snobbery.”

It’s interesting, Fix said, to consider that the Marxes’ films came out during times of economic depression and the rise of fascism. Was Harpo’s leg hinge a mockery of a goosestep? We know for sure that Mussolini took personal offense to Duck Soup.

And so, in his disruptive way, Harpo’s divine spark may have been performing tikkun olam, maybe even in the Lurianic sense of resetting the world.

If the Marxes are, as organizer Kathy Biehl said, motivated first and foremost by joy, it is not without purpose, but we have a task ahead of us as their inheritors.

As James Ferguson, who performs his burlesque Harpo under the stage name Tigger!, put it, in these absurd times “we desperately need some anarchy and joy and subversion.”

I took these marching orders to heart.

After seeing how the Marx clan brought people together as a chosen family, I found myself alone on a FaceTime call with my niece. At 18 months she’s not the greatest conversationalist, but when I flipped my phone to show her a video of Harpo strumming his harp, she sat mesmerized in her highchair. With any luck, I’ll keep it in the family.