Can we separate Woody Allen the artist from the man born Allan Stewart Konigsberg?

Patrick McGilligan’s doorstopper of a biography addresses Allen’s professional achievements and also his personal deficits

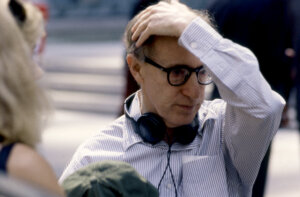

Woody Allen making his way through the media to the courthouse in New York where a judge gave Mia Farrow custody of their children. Photo by Getty Images

A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham: Woody Allen

By Patrick McGilligan

Harper Books, 736 pages, $50

Come December, God willing, Woody Allen will celebrate his 90th birthday with his wife, Soon-Yi, and their two adult daughters.

As a gag writer, stand-up comedian, screenwriter, and filmmaker, over 75 years the man born Allan Stewart Konigsberg has entertained, tickled, edified, and, more recently, divided, America. At 17, while a student at Brooklyn’s Midwood High in 1952, he adopted his professional name, typed wisecracks on postcards, and mailed them to columnists like Earl Wilson. Before long, Allen earned 75 cents for every joke that appeared in print. Soon, writes Patrick McGilligan in his 736-page biography of Allen: “Word spread about the kid from Brooklyn with the inexhaustible supply of energy and jokes.”

Despite its title (a line from Allen’s Bananas), A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham views both his work and the man himself in a mostly favorable light. As far as Allen, funnyman and filmmaker, is concerned, I’ve seen 50 of his 53 movies and 24 are great. (If he were a slugger, his batting average would be .453.) As far as Allen, the man, is concerned, don’t get me started. While rewatching his movies, I find that dialogue which convulsed me with laughter years ago now triggers me. From Fielding Mellish, the nebbish Allen played in Bananas: “I’m doing a sociological study on perversion; I’m up to advanced child molesting.” I laughed at that in 1971; in 2025, it sounds, uh…

The book’s epigraph, courtesy Gabriel Garcia Marquez, telegraphs McGilligan’s zones of interest. “Everybody has three lives: a public life, a private life, and a secret life.” (Full disclosure: I am quoted in the book as one of the 104 critics who voted on their favorite titles in Allen’s filmography. I said that I found it increasingly painful to watch Manhattan, the film in which Allen’s character has an affair with a 17-year-old played by Mariel Hemingway.)

This is McGilligan’s ninth film biography; his previous subjects included Fritz Lang, Nicholas Ray, and Orson Welles. Not only is he an excellent chronicler, but also a fine judge of films. His thoughts on Allen’s 53 films as a writer/director are a dependable guide to those that do – and do not – hold up. His Allen biography is a comprehensive chronicle of its subject’s public life and work, and it also details biographical elements both sweet and unsavory. For example, Allen has a sweet tooth for concession-counter candy found at movie theaters — and also for the sisters of his paramours Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow. McGilligan finds former lovers who confirm Allen’s interest in threesomes.

Besides Allen’s facility for jokes, as a teenager he had “a quadrant” of pursuits that evolved into perennial passions: Jazz, magic, movies and sports. As a Brooklyn boy who rooted for the Giants rather than his borough’s Dodgers, he was a bit of a contrarian. In Allen’s own 2020 memoir, Apropos of Nothing, he described his gun-toting father as “mob-adjacent.” McGilligan describes him as an outgoing guy who held various jobs, including taxi driver, and “mingled with with equal affability with organized crime.” Allen’s mother worked for a florist.

At Midwood High and New York University, Allen was, at best, “a middling pupil” and, at college, a habitual absentee. When it came to writing, though, he was enormously disciplined, ghostwriting celebrity and corporate anecdotes for a publicity firm and gags for himself. Though not a stellar student, Allen worked hard in the classes he liked. With pal Mickey Rose (co-writer of Bananas), he took private acting and photography lessons. Alone, Allen enrolled in a playwriting seminar taught by Lajos Egri, the midcentury guru of dramatic construction.

For the 19-year-old Allen, 1954 was a year of firsts. It marked Allen’s debut gig as a standup comedian, his first time performing in a jazz band with friends, and his first encounter with Harlene Rosen, then 15 or 16, who played piano for one of the band’s gigs. The pretty brunette would become his first steady and, in 1956, the first Mrs. Allen, later referred to as “Quasimodo” in his standup routines.

The “Woodman,” as the trade paper Variety dubbed him, was not an insult comedian. Yet when he adopted the persona of a stammering nebbish, the disparity between his gentle delivery and his stinging descriptions of others got big laughs. McGilligan contrasts Allen’s old-school humor about “ugly girls” with the revolutionary political satire Mort Sahl, whom Allen revered. Sahl joked about news, not people’s looks.

Sahl did not reciprocate Allen’s admiration, writing in his memoir that Allen represented “the degeneration of the Jew as a social force.” (Ouch.) Nevertheless, in the fall of 1955, Allen, 20, was tapped for the NBC Comedy Development Program, and in 1956 was sent to Los Angeles by the network.

The religious skeptic personally selected an Orthodox rabbi to preside over his Los Angeles wedding to Rosen, who had recently graduated high school. Their return to New York, where Rosen attended Hunter College and Allen worked on Stanley, a short-lived NBC sitcom with Buddy Hackett and Carol Burnett, was not auspicious. After three years of continuous and largely gratifying work, he had free time. He consulted a psychotherapist to talk about emotional intimacy and lack of creative fulfillment.

For three summers at Camp Tamiment (“South Wind,” to readers of Herbert Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar), Allen wrote and directed his sketches himself, without having a network, actor, or other director intervene. Unlike many writers, he encouraged performers to ad lib, if they could think of something funnier. Allen maintained that directing was never a goal, only something he did out of “self-preservation.”

In 1958, Allen rose from the minors to the majors when TV legend Sid Caesar hired him to join his stable of writers for a new comedy series on ABC. The others were Mel Brooks, Mel Tolkin and Larry Gelbart. His salary rose, too, to $88,000 annually, which has the buying power of $950,000 in 2025 dollars. He was not yet 25.

My head exploded when I read that Allen, along with the talented Gelbart, together wrote for Pat Boone’s variety show in 1959-60. It exploded again at how Boone, the wholesome Christian singer nearly as popular as Elvis Presley, reacted to an Allen pitch: “I’d slide down the wall laughing and sit on the floor at the audacity” of his ideas.

In 1960, Allen fired his agent and approached Jack Rollins and Charles Joffe, who represented Mike Nichols and Elaine May. Would the talent managers take him on, perhaps as a writer for the comedy duo? They told Allen that Nichols and May wrote and improvised their own material. Months later Allen returned and asked if Rollins/Joffe could manage his affairs. Nope, they only represented performing artists. Well, said the comic, he had thought of performing his own material. Before too long, Rollins told Allen if he would accept going through a trial period as a standup, they would consider representing him. Potentially, Rollins thought, Allen could become “a triple threat,” like Orson Welles: writer, director and actor.

Reaching the goal was arduous and took a decade for Allen to achieve.

“The trick in honing his stand-up act was to…become another person altogether,” says McGilligan. At first, when the audience didn’t laugh, he’d turn his back on it. Patience and warmth were not innate to him. Over time, they became integral to the stage persona of the stammering, nervous, nebbish unlucky in love who enlisted the sympathy of the audience and slowed down to hear its laughter. “The self-assurance that underlay this persona also provided him with [a life] that was its complete opposite,” McGilligan notes. Fame is a potent aphrodisiac.

The comic’s routine, loaded with humor about wine, women, and psychiatry appealed to Warren Beatty, whose agent offered Allen $35,000 to rewrite What’s New, Pussycat? (Beatty’s pickup line), about sex addiction. The 1965 comedy ultimately starred Peter O’Toole (as the addict) and Peter Sellers (as the shrink), who rewrote their own dialogue. Allen had a small part as a burlesque club’s wardrobe man, giving himself the funniest line in the film.

Before he and Rosen divorced in 1962, Allen became involved with actress Louise Lasser, whom he wed in 1966. The pair had an open relationship both before and during their marriage.

1966 turned out to be a very good year for Allen. While his script for the Broadway play, Don’t Drink the Water received mixed reviews, it ran 600 performances and Broadway took an interest in a second, Play it Again, Sam. And though his first credit as a film director, What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, was an absurdist stunt — he and his friends redubbed a Japanese spy movie into English, turning the dialogue into a hunt for the world’s best egg salad recipe — it earned him a three-picture deal with United Artists.

Allen’s discipline and productivity were astonishing. But by 1968 his commitment problem — more precisely, his overcommitment problem — might have scuttled both his Broadway and Hollywood careers. While editing Take the Money and Run, his first movie as a writer/actor/director, he was scheduled to audition actors and conduct rehearsals on his second play, the Casablanca parody, Play it Again, Sam. His managers and preview audiences found the film about the feckless bank robber remarkably unfunny. Allen left editor Ralph Rosenblum to reconstruct and rescue the film, principally by changing music to lighten the mood. Adding to the demands on Allen’s time, he and Lasser were talking about an “amicable” separation.

For the Broadway iteration of Play it Again, Allen transferred his stand-up persona to the character of Allan Felix, a movie critic, recently divorced, who gets relationship tips from a spectral Humphrey Bogart. Tony Roberts plays his best friend, whose work takes precedence over his marriage to Diane Keaton’s character, on whom Allan has a crush. It wasn’t the actress’ first time on Broadway, where she had appeared in Hair. Her mercurial performance opposite Allen earned Keaton a Tony nomination, and she would become, briefly, Allen’s girlfriend, and ultimately, a lifelong friend.

While admiring the depth and breadth of McGilligan’s research, by page 268 — with nearly 500 pages more to go — I commiserated with Vivian Gornick’s 1976 Village Voice essay in which she despaired, “I feel as though I’d been watching Woody Allen try to get laid for 20 years now.”

What I liked best about A Travesty is how it enabled me to see Allen’s professional achievements and his, shall we say, personal deficits more clearly.

Here is a filmmaker who evolved from sophomoric slapstick like Take the Money and Run (which incited bellylaughs), to an unsparing portrait of complex humanity like Crimes and Misdemeanors (an unsettling tragicomedy which provoked both laughter and horror).

Here is a filmmaker who, while auteurs Francis Coppola and Martin Scorsese chronicled the world of men, created multidimensional characters for actresses like Keaton, Mia Farrow and Scarlett Johansson.

And, lord knows, here is a man who denied there was an incestuous dimension to his affair with the daughter of his partner of 12 years because he and Farrow weren’t legally married, and Farrow’s daughter Soon-Yi was adopted. It wasn’t a legal issue; it was a moral one.

So concerned was Farrow about Allen’s “inappropriate” behavior around their 7-year-old daughter, Dylan (whom Allen had legally adopted), that she was oblivious to signs of Soon-Yi’s affair with Allen before she found pornographic photos of Soon-Yi at his apartment. Months later, when Dylan complained to her that Allen had touched her privates, child abuse was added to Farrow’s briefs against Allen.

The ensuing 33 years of accusation, litigation, investigation and character assassination have been an ongoing nightmare for all involved. Because of different findings in Connecticut and New York, child abuse charges remain inconclusive. Dylan Farrow is now 39.

While recounting the Allen vs. Farrow saga, McGilligan is even-handed until surprisingly, in the biography’s last 50 pages he frames Allen as a victim of the #MeToo movement. McGilligan quotes Robert Weide, director of an American Masters profile of Allen: “The day is coming when every actor who has denounced #WoodyAllen will be as proud of their decision as those who named names in the McCarthy hearings.”

Unlike Weide, I don’t believe that Allen was a victim of the witch hunts. McCarthy wanted Hollywood to prevent liberal actors from making a living. #MeToo wanted to prevent predators from forcing themselves on women and girls.

I think most of us can hold two conflicting ideas at the same time. Me, I continue to love approximately half of Allen’s movies, even while I flinch at certain lines. Knowing Charlie Chaplin was fond of underage girls, I also flinch sometimes watching Chaplin movies. And knowing that Picasso emotionally or physically brutalized many of his models, I can still look at, and even admire, his portraits. Yes, I still like many of the films of Woody Allen, filmmaker. But I wouldn’t want him to date — or God forbid, marry — either of my daughters.