‘No matter what, I will always be a Jew.’ Billy Joel opens up about his family’s Holocaust history

The singer-songwriter speaks in depth about antisemitism in new HBO documentary ‘And So It Goes’

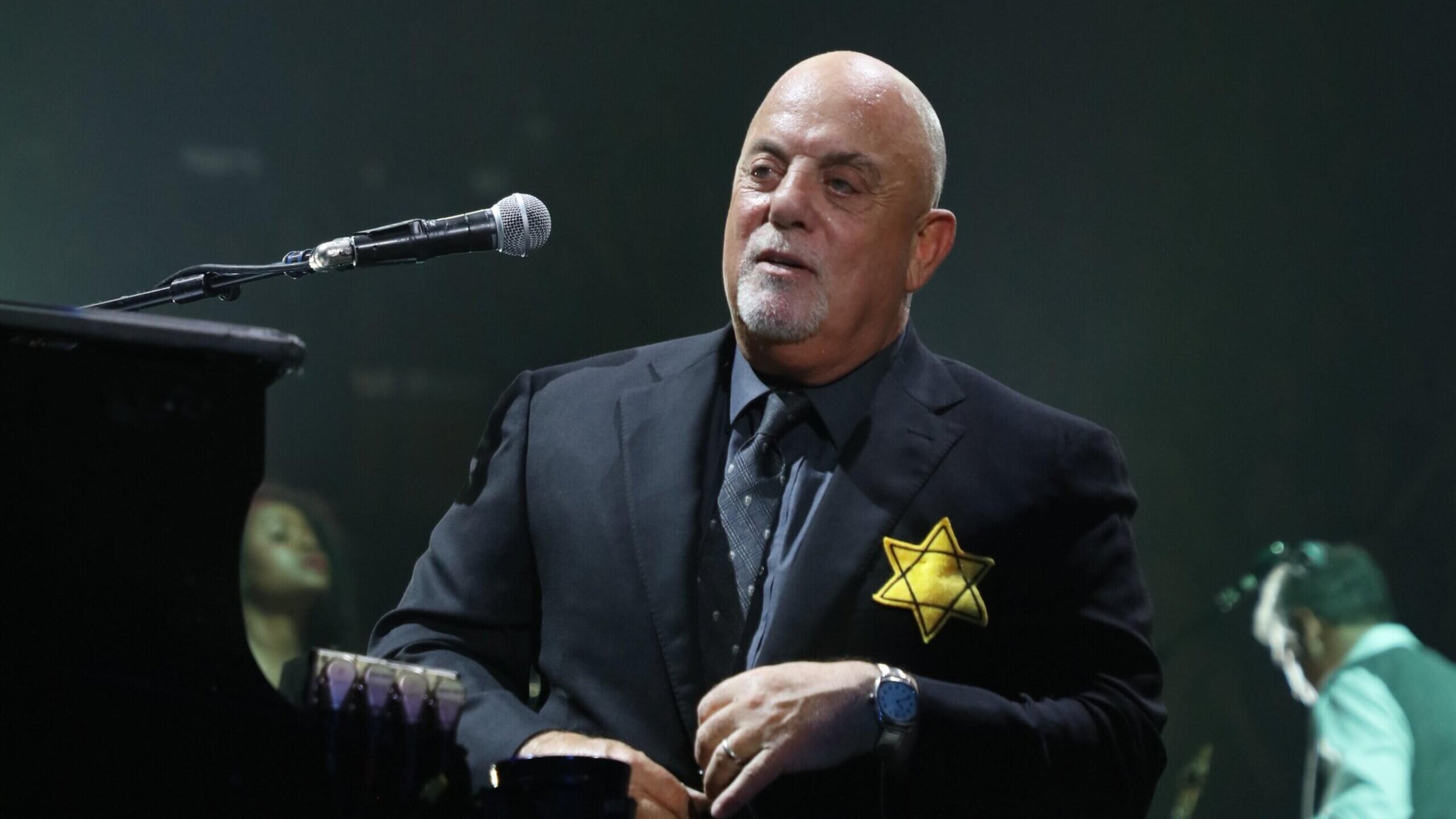

Billy Joel wears a jacket with the Star of David during the encore of his 43rd sold out show at Madison Square Garden on August 21, 2017 in New York City. Photo by Myrna M. Suarez/Getty Images

In the second installment of And So It Goes, HBO’s new two-part documentary about Billy Joel, the Piano Man explains why he wore a yellow Star of David in August 2017, during his residency at Madison Square Garden, in his most extensive filmed account of his family’s experience in the Holocaust.

“I was angry,” Joel, who wore the star on his jacket in the aftermath of the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, said in Susan Lacey and Jessica Levin’s documentary, the first part of which debuts July 17. “Here they are marching through an American city saying ‘Jews will not replace us.’ We fought a war to, you know, defeat these people.”

Joel also called out Donald Trump for his infamous remark that there were “very fine people on both sides” of the rally. (Trump, some note, said he didn’t mean neo-Nazis and white supremacists, but others attending the rally, spearheaded by white supremacists.)

“He should have come out and said, ‘Those are bad people,’” Joel said. “There is no qualifying it. The Nazis are not good people. Period.”

Joel said he wore a star to say — and here he put a hand to his heart — “No matter what, I will always be a Jew.”

‘I can’t imagine the trauma’

The wide-ranging documentary explores Joel’s father’s family history, mostly unknown to him until he was in his 20s.

His father, Helmut (who went by Howard in America), came from a wealthy family that owned a textile factory in Nuremberg. The Joels were well-assimilated and proud to be German.

“My father got bar mitzvahed and that was it,” said Joel, who, reflecting on his own areligious upbringing in Mark Bego’s 2007 biography, referred to his circumcision as “as Jewish as [his parents] got.” “They really didn’t go to synagogue. But in Germany, if your family was Jewish you were a Jew.”

Helmut was 10 when Hitler became chancellor. His family home was next to the Luitpoldhain, the park where the Nazis staged their party rallies.

“My dad would look over the fence while they were doing all these antisemitic speeches, and see this going on,” Joel said. “I can’t imagine the trauma to watch the SS parade espousing these principles.”

In time, Helmut, like all Jewish children, was forced out of school and the family was stripped of their rights.

Julius Streicher’s antisemitic paper Der Sturmer inveighed against Helmut’s father as the “Jew Joel.” The business suffered from the Reich’s antisemitic policies and the family was forced to sell it to an Aryan at a loss — the amount of which, Joel said, was never recouped.

The family managed to escape over the Swiss border just in time.

“If my grandparents had been found on the train with the documents that said ‘Jew,’ they would have been sent immediately to a concentration camp,” Joel said. “They got out. A miracle.” (As recorded in Bego’s biography, they fled with forged passports and landed in New York via England and Cuba.)

But Joel notes an extreme irony. After his family sold the business, the factory began making other items.

“They actually started to manufacture the striped pajamas that the prisoners in the concentration camps had to wear,” Joel said. “That was made by Joel Macht Fabrik.”

‘We found your father’

Joel’s father, himself a classically trained pianist, left him, his mother and his sister when Joel was 8 and didn’t stay in touch.

Touring Europe in his 20s, Joel looked for Helmut, who he knew was living there, having left the United States, troubled with its own problems with antisemitism and contemptuous of what he saw as its lack of refinement.

As Joel was about to leave he got a telegram saying “we found your father” — he was in Vienna.

Joel went to his apartment and saw a 5-year-old boy there: his half-brother, Alexander, who seemed to be having a much happier childhood than he had.

The relationship between Joel and his father remained distant, and it was only through Alexander, now a pianist and conductor, that he learned most of the Joel family was murdered at Auschwitz, and the trauma their father, who after moving to the United States served in the Army under General George S. Patton, underwent liberating Dachau.

“The first week he was there after it was liberated and saw the terrible things, it was something that deeply traumatized him,” Alexander Joel says in the documentary.

Joel believes that his experiences explained some of the behavior of Helmut, who was abusive and dark, once knocking the young Joel unconscious when he heard him adding rock ’n’ roll riffs to the “Moonlight Sonata.”

While it was always difficult for Helmut and Billy to connect, their reunion prompted Joel to write his song “Vienna.” And in the documentary, we see Joel and his father play piano opposite each other, a rare display of harmony.

Joel seems to have an ongoing interest in what his family suffered under Hitler. “I’m still trying to put the pieces together,” he said.