‘Bojack Horseman’ creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg on his new, ‘unapologetically Jewish’ family affair

At the heart of Netflix’s ‘Long Story Short’ is what it means to be a Jew

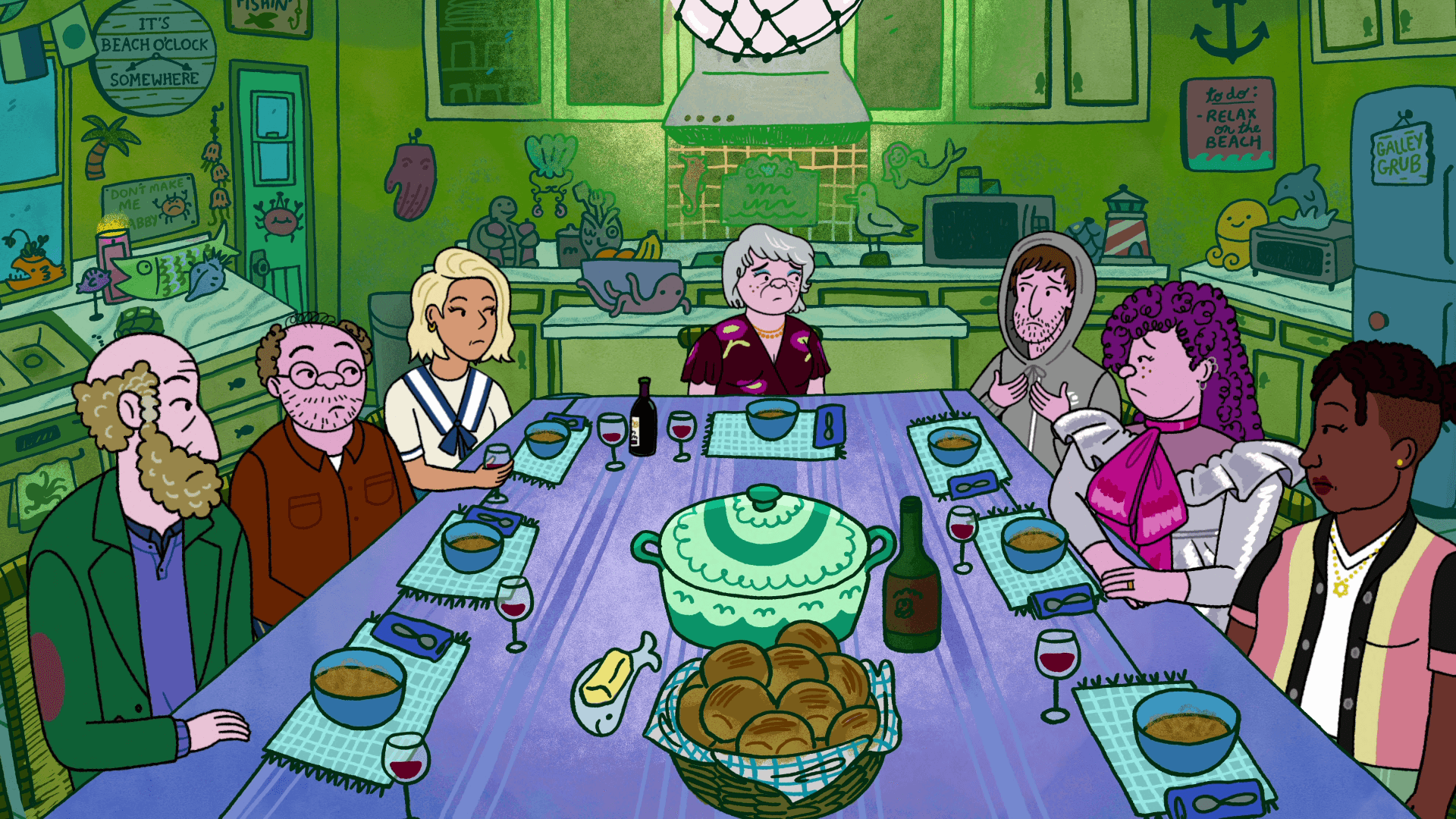

The Schwooper family of Long Story Short, on their way to Bubbe’s gravesite. Courtesy of Netflix

We meet the Schwooper family — whose name is a portmanteau of Schwartz and Cooper — on a motorcade to a burial in 1996. For many Jews, it may feel like a homecoming.

The matriarch, Naomi, is bereaved for the loss of her mother but maybe more annoyed by the rabbi’s Mad Libs-style eulogy. They’ve lost track of the hearse and the children bicker in the back. Naomi quickly shuts down the idea that Bubbe has been reunited in death with her husband, but as the children reel from the concept of no afterlife in Judaism, a different perspective is introduced.

Jews focus on the here and now, the Schwooper patriarch, Elliot, adds: “You don’t lead a good, meaningful life for some reward later. You live a good, meaningful life so that you lead a good, meaningful life.”

In these opening moments, Long Story Short, the new Netflix animated series by Bojack Horseman creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg, lays out its major theme: what it means to live a full life, and, as a corollary, a Jewish one. (Spoiler: There’s no one way to do it.)

“I wanted to tell a story that was unapologetically Jewish without feeling the pressure to do the things that a Jewish show might have to do or address,” said Bob-Waksberg, who grew up in a very Jewish milieu in Northern California (day school education; mom owned a Judaica store; father helped Soviet Jews escape the USSR). “And the only way I know how to write Jewish is to write in the way that I understand it and the rhythms of my family and the people that I know.”

While not really autobiographical, Bob-Waksberg hopes the series, told non-linearly with episodes set in the ’90s, aughts and 2020s, sparks recognition. But it doesn’t hurt if you know from Jews.

Its plots involve a row over a candle for a deceased relative at a bar mitzvah (prompting the tearing of a $108 check to the ADL); baking knishes for a potluck for prospective parents at a day school (for children named Walter and Benjamin); a fib that leads to an epiphany during Yom Kippur Viddui confession (and a joke about the distinction between Litvaks from Vilna and ones from Vitebsk).

Bob-Waksberg anticipates many will see themselves in this lovingly flawed, supremely Semitic family, which is also queer, Black and interfaith, Conservative, Orthodox and non-affiliated.

“I think people might even be surprised by the ways in which they can relate to characters that maybe, on paper, don’t seem like them at all,” he said.

I spoke with Bob-Waksberg over Zoom about how becoming a parent inspired the show, being unafraid to go deep on Yiddishkeit and the animated Jewish Easter eggs (er, afikomans) hidden in the backgrounds. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to tell this kind of a story, more rooted in reality than your previous work, and obviously quite a bit more explicitly Jewish?

Part of it was I had kids since my previous work. When you become a parent, you think about family more and in different ways, thinking about “What choices am I gonna make for my kids, and how am I going to raise them?” I think about the way I was raised, and what from my parents do I want to emulate, and what from my parents do I want to correct — knowing that I will not get it 100% in either direction and I’m going to screw things up!

I was thinking about family a lot, and then thinking about all the ways that identity connects to that, whether that’s Jewish identity, or your identity as a son versus as a father or a brother or a spouse, and how you define yourself, and the way that that is defined for you a little bit by your family, and how you might try to escape that or embrace it.

And of course, we see how each of the siblings relates to that tradition. It begins and ends with this question of what it means to be a Jew. Did the process of the show change the way you thought about that idea?

I think this show has actually been really helpful for me in articulating some of these thoughts that I’ve had. But because it’s not an essay, I don’t have to decide anything. I can kind of explore it. I can have these conversations through my characters.

But I remember when I was in fourth grade, I had this Judaica teacher, Riva, and we had this thing we did in class where the topic was, “What makes a Jew a Jew?” And she had this like puzzle of a person, and the different pieces had different Jewish attributes, like, “observes the holidays,” “keeps kosher,” “believes in God,” you know, “is married to a Jew.”

And she would take away the pieces one by one and go, “Is this person still a Jew? What about in this combination?” And I revisit that a lot. I think my answers have changed quite a bit since I was in fourth grade to what makes a Jew a Jew. And I’m not sure there is any one thing. I couldn’t define a Jew in a way that only includes Jews and doesn’t include any non-Jews. It kind of is a loose, “I know it when I see it” kind of thing, while also acknowledging that people might know it when they see it differently than me.

Thinking about what Judaism is, and what Jewishness is, and what it’s for — what the purpose is — I am not someone who believes that we are doing this because the Torah tells us to do it, so we have to. I’m someone who believes that we choose to be Jewish, and that, without being too transactional about it, we should get something out of it. And so I am constantly thinking, “Why do we do these things, and what is the benefit?” And that maybe sounds cynical, like there isn’t one, but I think if you watch the show, you might see maybe there is.

There’s a way that the show could have been sort of generically Jewish, or had, like, kind of the flavor, or a whiff of a hint of Jewishness. What is your philosophy on bringing that specificity in here, not over-explaining things, making sure that it still resonates?

We had writers in a writers’ room who were Jew-Jews. We had writers in a writers’ room who were Jews, but maybe didn’t get all the day school references. And we had writers in a writers’ room who were not Jewish, who didn’t really know a lot of Jews, and everyone seemed to enjoy it. And that’s true in every stage of the process. We have actors on the show who get everything, and actors on the show who are like, “I’m along for the ride, and this is great.” And nobody has ever said, “this is too much,” or “whoa, whoa, this is maybe not for me.” So we have kind of these checks and tests throughout the process.

But I always felt like when I’m watching something as an audience, I want to be dropped into that world, like I want just enough that I can try to keep up. That’s exciting for me. There are jokes on the show that I didn’t get at first, that had to be explained to me. I think it also helps make the family feel real that they have these inside jokes and references that maybe you’re not a part of. I think it makes it feel like, “Oh, these people really know each other. They have this common language.” And in my family, a lot of that stuff is Jewish-related. And I would hope that audiences wouldn’t be intimidated by that. But if they might be, I would say, don’t tell them? Let them watch the show and see for themselves.

You’re working with cartoonist Lisa Hanawalt again, like on Bojack. The aesthetic is very different. And also all these visual easter eggs that we see, obviously, like ketubot and menorahs.

I would say visual afikomans.

Visual afikomans, good punch-up. What was the idea?

From the beginning with Lisa, we were both very conscious of, we don’t want this to look like Bojack. I mean, obviously it’ll feel like it in some ways, because she does what she does, and I do what I do as a writer. But we didn’t want it to feel like Bojack himself could walk through the frame at any moment. We wanted it to feel like its own distinct world.

We talked a lot about how, in our experiences in animation, both in making it and watching it, sometimes you get these very charming drawings and initial designs which then kind of go through the animation machine, and they end up feeling more flat and puppetty or perfect. And so we really were precious about, “Let’s hold on to the charm of the loose drawing. Let’s make this feel loose. Let’s let the characters move in a loose way. Let’s have the lines on the drawings not always connect. We can color outside the lines a little bit.”

I think they had a rule for the artists: no straight edges for drawing lines. Everything is done freehand. And then there’s some deliberate choices to make the perspective a little wonky in some places, or to make some characters’ heads a little misshapen, because, again, we wanted it to feel loose and visceral in that way.

Do you feel that there’s a need to tell Jewish stories like this?

I think that there is a wide diversity of Jewish life, and there are all kinds of Jews. And I think the more stories we tell, the more ways we can define ourselves, not as a bloc and as all one thing, the better it is for everybody. So yes, I’m really proud that on my show I can show some things that I haven’t seen a ton of in even Jewish stories, while also knowing that there are all kinds of Jews I don’t even touch on my show.

I had a driver the other day who was Iranian Jewish, and we talked about that and his experience. It’s like, “Yeah, I’m not using that now. Maybe at some point I will.” But I couldn’t possibly check down the list of every kind of Jew, so I want to create opportunities for more people to tell their stories, or for people to watch my show and go, “Well, that’s not really what my family was like; let me tell that story.”

It returns to the lesson in the Judaica class. Something that’s so great about this, and I’m guessing that this is drawn from life a little, that phenomenon of cooperative overlapping is very much in this.

That is very much a choice on the show. The way we structure the dialogue, where we write it — most shows don’t do it like that. And the nice thing about animation is there are technical ways in which it is easier, because we record all the actors separately, and so we can actually, in the edit, make sure everybody is being heard the way we want them to be heard.

They’re not actually talking at the same time. So we can inch someone back, like a half a second. We want to make sure this person gets this word in. We can take the volume out of this person. The levels are different, which gives us a lot of control. There’s a lot of dual dialogue in our scripts, and then often in the edit, we’ll be like, let’s squeeze it even more. She should not wait for him to finish his sentence before she starts talking. They should all be talking, multiple conversations happening at once. I get the gist of what you’re saying and I’m going to respond. I don’t need you to get to the period. And notice how I did that to you as you were asking the question.

Look, we’re two Jews talking, it’s gonna happen.

Long Story Short debuts on Netflix Aug. 22.

Clarification: A previous version of this article stated Bob-Waksberg’s father resettled Soviet Jews. More accurately, he helped them leave the USSR.