A Jewish lawyer sued Henry Ford and changed how we think about hate speech

The documentary ‘Sapiro v. Ford’ explores how Aaron Sapiro took on the father of the Model T

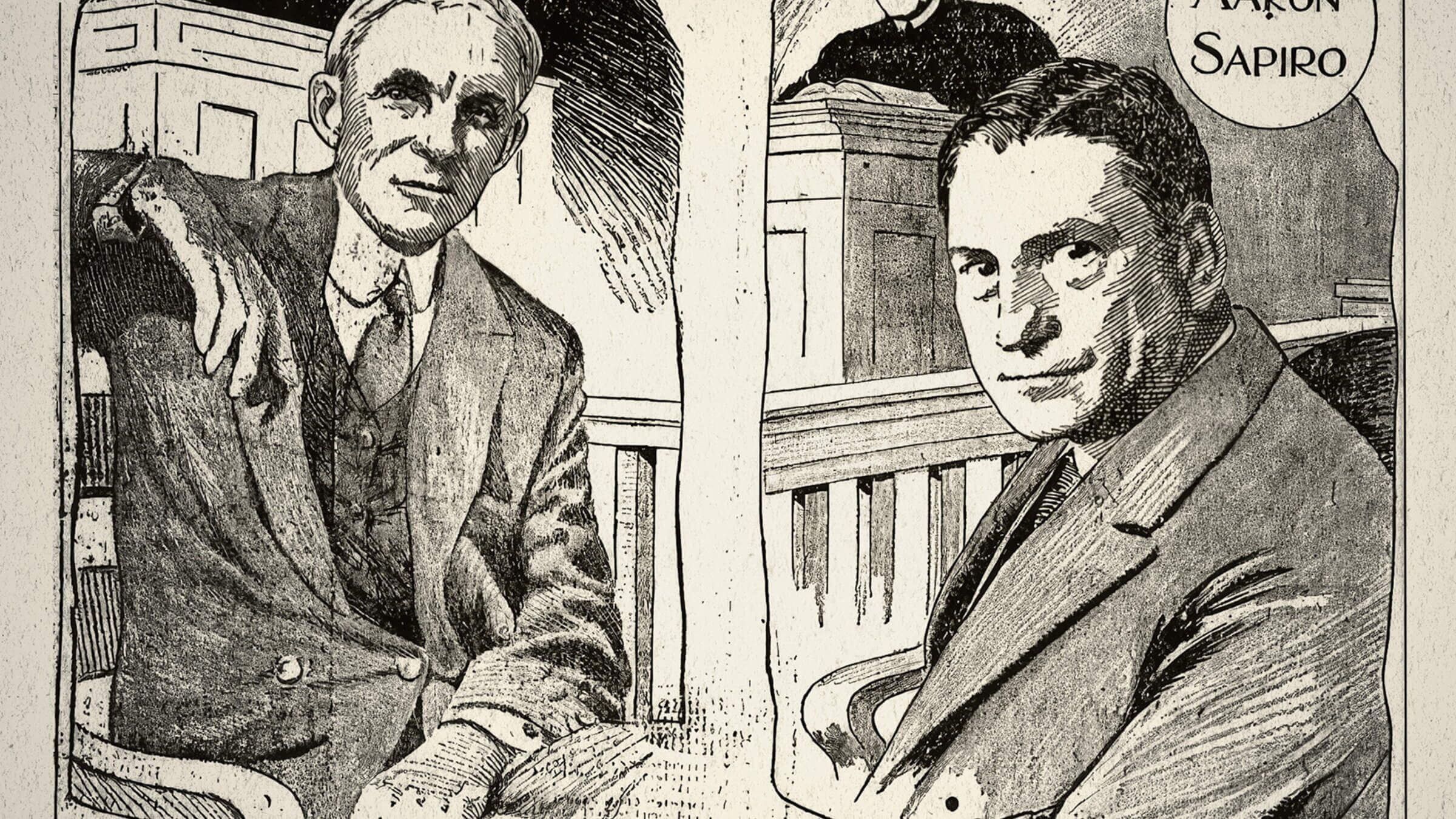

A cartoon depiction of the trial between Henry Ford and Aaron Sapiro from 1927. Image by Art Krenz via Michael Rose Productions

When Jewish lawyer and labor leader Aaron Sapiro sued Henry Ford for libel, he was doing more than trying to save his own reputation. Described by Jewish history professor James Loeffler as “the first modern hate speech trial in America,” the case disrupted Ford’s ability to publish antisemitic conspiracies in his paper, The Dearborn Independent.

Sapiro took Ford to court in 1925 for publishing 21 articles attacking him as a “globalist” Jew trying to take over the agriculture industry. The documentary Sapiro v. Ford: The Jew Who Sued Henry Ford, directed by Gaylen Ross and produced by Carol King, explores the case through archival materials, interviews with historians, and Sapiro’s own writings, recited by actor Ben Shenkman.

“It’s a David and Goliath story,” King said in an interview. “He took on the most powerful, richest man in America at the time.”

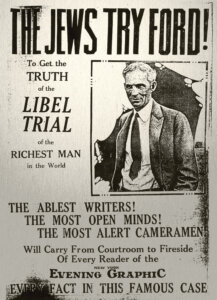

The Dearborn Independent was once the second-largest-circulating newspaper in America, spreading Ford’s antisemitic theories across the country. The legacy of his antisemitism was so strong that Ross’ “family never had a Ford car” when she was growing up in the 1950s. King is not Jewish but was raised in Detroit, where Ford’s company was headquartered. She said his antisemitism “was always talked about as sort of a quirk.”

Sapiro himself didn’t understand the gravity of Ford’s words at first.

“He thought, ‘Who’s gonna believe that stuff? It’s so outrageous,’” King said. “As it turns out, a lot of people did believe it.”

King remembered Ford’s “weird ideas” such as that baseball and jazz were rotting American society — and he blamed their popularity on the Jews. His words had a global impact: Hitler praised Ford in Mein Kampf and, at the Nuremberg trials, Baldur von Schirach, former head of the Hitler Youth, credited Ford with inspiring his own antisemitism.

When Jewish merchants told Sapiro that Ford’s articles were driving away their customers, Sapiro realized he had to try to stop the conspiracies.

“This was one person who stood up, not just for himself — that was important — but also for his community, for his fellow Jewish people,” King said.

King started working on the film over a decade ago with her husband, Michael Rose, a filmmaker who provided archival material for Michael Moore’s Roger & Me and worked on the documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin? They spent 10 years researching the Sapiro case and gathering archival materials, but when Rose became sick with leukemia, the project went on indefinite hiatus. He passed away in September 2020.

Before he died, he had shown Ross, known for her documentary Killing Kasztner, an extended trailer for the project. Ross later offered to help King complete the film.

“How could I say no? It was a gift to me at a time when I needed something badly,” said King.

Ross was particularly interested in making Sapiro’s story more widely known.

“Sapiro, in the Jewish canon, didn’t exist,” Ross said. “He was essentially erased.”

Born to a poor family in San Francisco in 1884, Sapiro survived being abandoned in an orphanage and overcame financial hardship to eventually graduate from the University of Cincinnati College of Law. He worked with the National Farmers Union and introduced a new method of agricultural unionizing that allowed farmers to pool their resources and have collective market power.

Because the Model T had also revolutionized farming, Ford saw himself as the champion of the American farmer and was alarmed by Sapiro’s sudden influence. He was particularly troubled by Sapiro’s visits to farmers in Canada.

“Sapiro could organize farmers and cooperatives all over the country,” Ross said. “But crossing the border made him an example of international Jewry and the conspiracy that Ford believed in.”

The film brings Sapiro to life using Shenkmen to recite his speeches and writings, although it omits some aspects of his life, such as his association with Al Capone that made him the subject of trade racket investigations in Chicago.

Ross and King say Sapiro’s story has implications for understanding modern hate speech. An opening montage of antisemitic headlines from the 1920s — “The Jewish Control of the American Press,” “Jews Are The Curse Of America” — is promptly followed by footage from recent neo-Nazi and white supremacist rallies, offering a warning about what happens when bigotry goes unchecked.

“Not only was he prophetic in worrying about what would happen in a society that condemned not only the Jewish community, but people who were different and refugees,” Ross said of Sapiro. “But his focus on democracy — and he says it strongly — that democracy is not just about politics; it’s about how you live your life and how you collaborate and work together.”

The documentary Sapiro v. Ford: The Jew Who Sued Henry Ford is showing at the New York Jewish Film Festival starting Jan. 21 and the Palm Beach Jewish Film Festival starting Jan. 29.

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly stated the role of Carol King. She is the film’s producer, not a co-director.