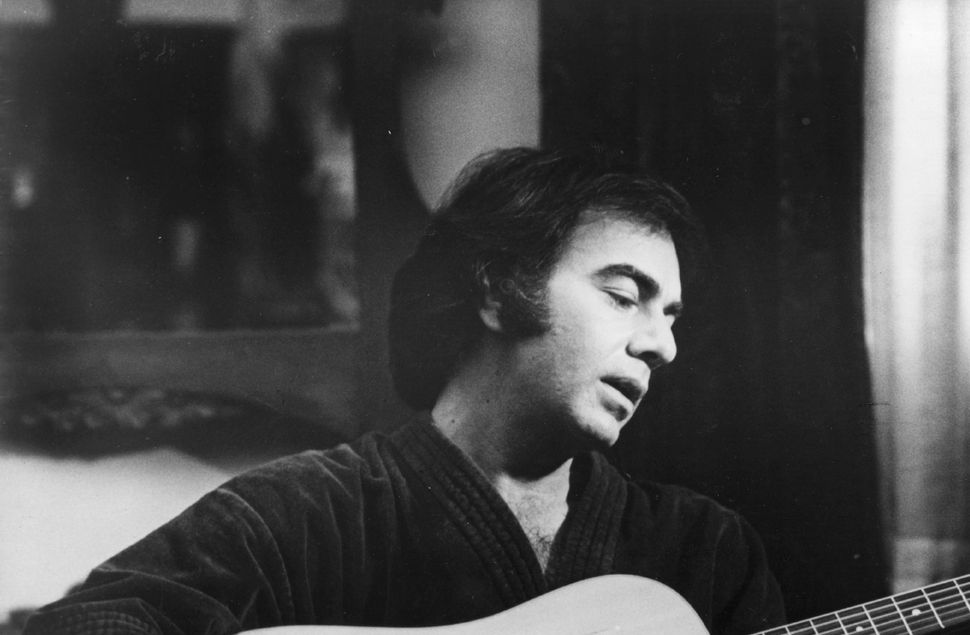

Why Neil Diamond Still Matters

Image by Getty Images

Back in 1967, in the midst of his initial run of brilliantly pithy three-chord pop singles, Neil Diamond cut a pair of radio jingles for Coca-Cola. One of them was an upbeat rocker in the Latin-tinged “Cherry, Cherry” vein, the other a slow strummer that built to a crescendo a la “I Got the Feelin’ (Oh No No),” a Top 20 hit from late 1966.

Neither the existence of these jingles nor their imitative nature is particularly remarkable; it was common practice for hit acts of the time to make some extra cash by writing and recording sound-alike advertisements for various consumer products and services. (Cream, for example, once recorded a jingle for Falstaff beer that sounded like the Cream song “Sunshine of Your Love” flipped over onto its side.) What is unusual, however, is the amount of sheer, unadulterated Neil-ness present in the two recordings: The rockier number finds the agitated singer begging his girl to stop bugging him about planning their wedding, while the slow one is a brooding meditation on being proudly out of step with an excessively consumerist society. “Got my own piece of shade / Count all the money I ain’t ever made,” he sings. “I ain’t got a single plan / Wind in my face and a Coke in my hand.” (The ad execs who’d commissioned the jingles must have just shaken their heads and remarked, “Well, at least they’re tuneful!”)

While Diamond’s Brill Building-honed knack for winning melodies and indelible hooks has obviously been the major factor behind his massive success (more than 125 million records sold worldwide, and counting), his prickly but determined sense of self has been an intriguing thread that’s run throughout much of his music and career. You’d have to go all the way back to 1963 to a Neil Sedaka-esque stiff called “At Night”) to find a Neil Diamond recording that sounded like anyone other than, well, Neil Diamond; by his next single, the 1966 “Solitary Man,” the Neil Diamond sound as we know it had already fully coalesced. The persona embodied in that song — the melancholy loner with something to prove — would reappear repeatedly in his songs, even after Diamond had transformed himself into the denim-clad sex god of the 1972

“Hot August Night,” or the jump-suited “Jewish Elvis” of the ’80s and beyond. And that melancholy loner was certainly present at his recent sold-out Hollywood Bowl concert, even if he was largely obscured by hefty servings of schmaltz, glitz and (mostly) nonstop hits.

Of course, schmaltz, glitz and hits are part of what we’ve come to expect from a Neil Diamond show, and when I caught up with him at the Hollywood Bowl on his current tour, he didn’t disappoint. The singer entered the stage via a giant hologram of a rotating diamond — which proceeded to change colors throughout the show, to match the mood of the songs — and spent much of the early portion of the concert shaking the outstretched hands of the fans in the front rows. “It’s a big thrill to hear the ladies still screaming my name,” he cracked at one point. “It makes me feel like I’m 70 again.”

And scream they did, especially during the one-two seduction punch of “Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon” and “Play Me,” both of which were delivered impeccably, even if the sentiments of the former song did sound a bit creepy coming from the lips of a 74-year-old grandfather. “The Art of Love,” one of two songs in the set from his 2014 album, “Melody Road,” also elicited some serious screams and swoons.

Mostly, though, Diamond was there not to play the “love man,” but rather to celebrate a representative cross-section of his impressive song catalog, a duty in which he clearly delighted. Ably abetted by a dynamic 11-piece band (which included a four-piece horn section) and two backup singers, he dipped into his bag of early three-chord rockers (“I’m a Believer” opened the show, while “Kentucky Woman,” “You Got to Me,” “Cherry Cherry” and “Crunchy Granola Suite” also found their way into the set list), served up some blockbuster ’80s balladry (“Hello Again,” the encore-closing “Heartlight”) along with some underrated ’70s hits (“If You Know What I Mean,” and a particularly stunning rendition of “Holly Holy”), and got the 18,000 fans in attendance to join in on such infectious sing-alongs as “Red Red Wine,” “Forever in Blue Jeans,” “Cracklin’ Rosie” and the inevitable “Sweet Caroline.” With the exception of some rough notes on “Love on the Rocks” — which might have been placed too early in the set for the good of his vocal cords — Diamond’s baritone sounded superb and strong throughout the evening, and he seemed as genuinely jazzed by the crowd’s ecstatic reaction as they were by his singing.

But however seamless his singing or slick his presentation, there are always points in a Neil Diamond concert where certain eccentricities remind you that you’re not just dealing with an expert middle-of-the-road entertainer. There’s his eccentric pronunciation, which occasionally results in words like “tune” drawn out as “teeeeeeeeeee-une.” There are times when, either by nature or design, he brings down the party by blurting out things like, “This song is about an old man who died alone,” which is how he introduced the song “Morningside” that night — and which is the sort of thing that would surely earn him an “F” from the Paul Stanley School of Stage Banter. And there are also those moments when the bruised but unbowed loner of yore returns to ponder how far he’s come, while still reminding you of the sadness and alienation that lie at the heart of many of his best songs.

A particularly moving example of the latter occurred a little more than halfway through the set, when he sang “Brooklyn Roads” and “Shilo” back to back. The songs, which appear together on his underrated 1968 album “Velvet Gloves and Spit,” are two of his most personal works; the former a wistful reminiscence of growing up in Brooklyn (home movies and photos of the Brooklyn Bridge were screened to evocative effect, while the song was played at the Bowl), and the latter a heartbreaking account of a lonely and isolated child who takes comfort in an imaginary friend, yet still carries those feelings of loneliness and isolation into adulthood. On that Tuesday night, it was clear from his reflective preamble to “Brooklyn Roads” and his emotional reading of both songs that, for all his success, there’s still a lonely little kid inside of Diamond who is profoundly grateful and amazed that people would want to come and hear him “sing my heart out,” as he put it.

Though penned a few years after “Brooklyn Roads” and “Shilo,” Diamond’s 1971 hit “I Am… I Said” is really the third part of the trilogy. The “frog who dreamed of being a king and then became one” stands up to the Goliath of self-doubt and holds it at bay, even while acknowledging that the success he’s achieved isn’t going to vanquish his loneliness. However ridiculous the song’s “not even the chair” line may be, “I Am… I Said” remains a powerful statement of self-actualization, and it ended the main part of the show’s set on a majestic and uplifting note. The moody introvert who once defiantly faced down the wind with only a Coke in his hand was still with us — only now, instead of taking on the elements, he vanished into a door hidden at the base of a giant diamond-shaped hologram. There’s a lesson for all of us in there somewhere.

Dan Epstein is the author of “Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ’76” (Thomas Dunne Books, 2014).