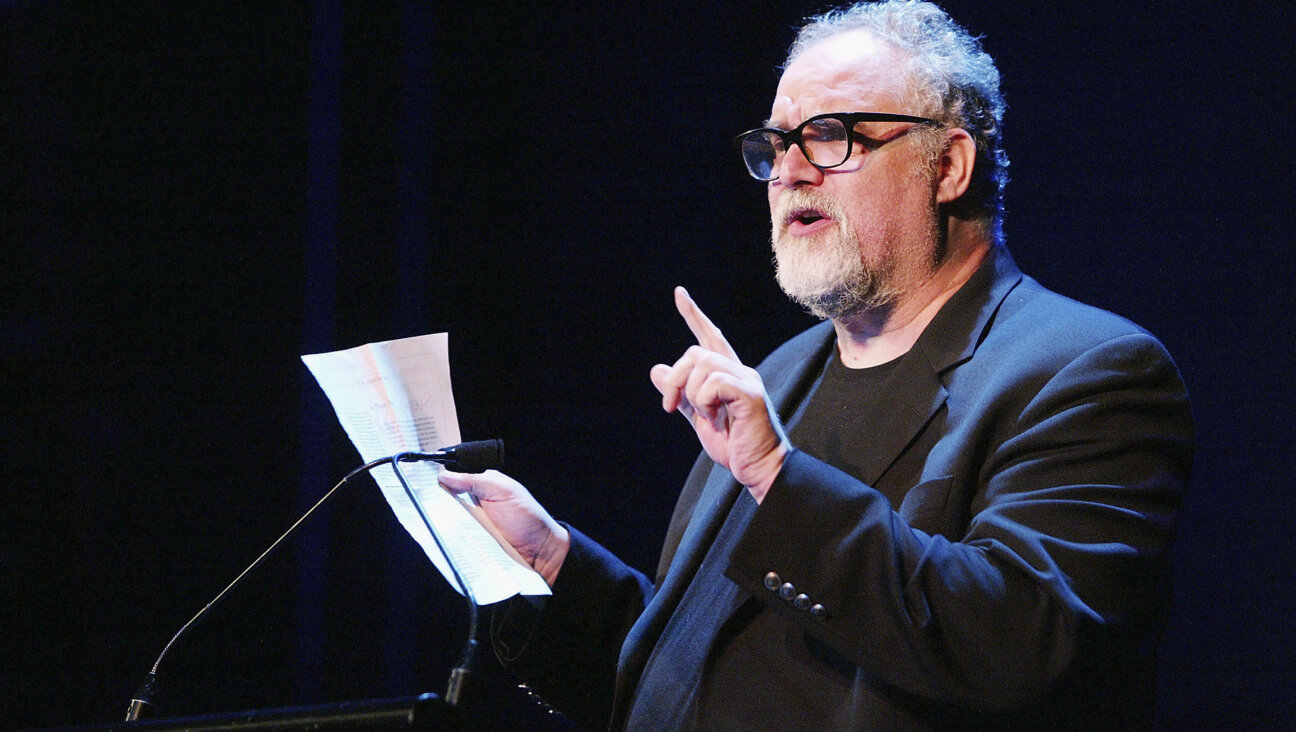

David Mamet Finds God, Still Searches For Inspiration

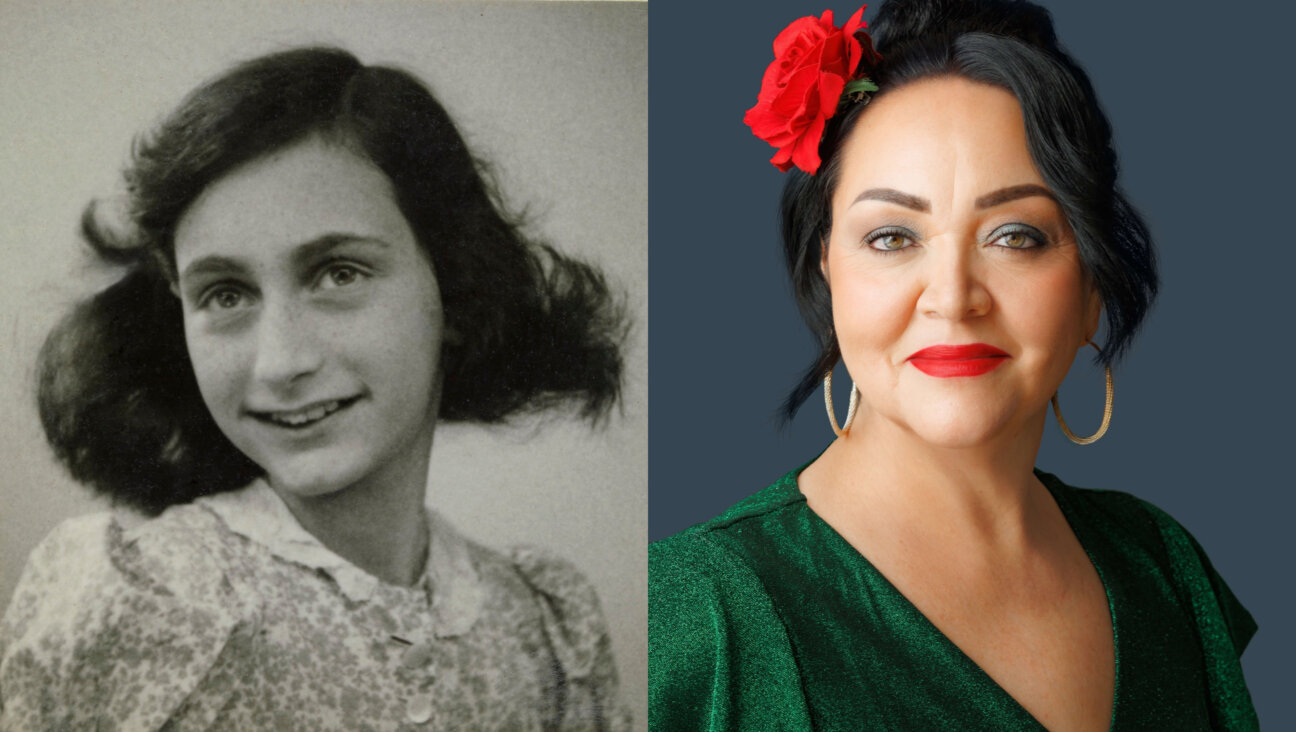

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

David Mamet has written a new play, and, unlike his last three new ones produced in New York, it is not offensively bad. It is merely not at all good.

That’s not quite true. It is potentially, slightly, maybe a little bit good. It is centered on a kernel of a good and interesting idea: What is it like to be the psychiatrist of a man who commits a heinous crime? And what effect will that crime have on the psychiatrist, the psychiatrist’s family, the psychiatrist’s life? That is the crux of “The Penitent,” which opened last night at the Atlantic Theater Company — the company Mamet co-founded, and with its artistic director, Neil Pepe, directing.

Unfortunately, and inevitably, that glimmer of possibility is soon extinguished under the weight of the play’s plotting (which diverts into an endless stream of mini-screeds, about journalism and Judaism and identity politics), its direction (which follows the recent trend, epitomized in “The Anarchist,” that Patti LuPone-Debra Winger act of domestic terrorism, of Mamet characters talking to each other in affectless, undifferentiated Mamet-parody volleys), its costume design (which for some reason dresses the psychiatrist as, more or less, Mamet), and its performances (including an unwatchable one from Rebecca Pidgeon, Mamet’s wife, who is unkindly required to repeatedly bray “but I don’t understand” and for some reason repeatedly pronounces it “understahnd”).

(The set is nice, though, a minimalist suggestion of an office or meeting room turned gladiatorial stage by two rusted-metal upstage walls — a sort of un-torqued Richard Serra sculpture. It’s by Tim Mackabee, who is alas, true to his name, fighting a fruitless battle against a domineering oppressor.)

Chris Bauer, in a series of sweater vests and horn-rimmed spectacles seemingly identical to the playwright’s, plays Charles, an apparently prominent psychiatrist. A patient of his has committed a mass shooting, and he is refusing to testify on the boy’s behalf. He has testified countless times before for other patients, weighing in not on their actions but simply on their state of mind, their psychological state. But this time he cannot. His morals will not allow him. And this, somehow, becomes a quagmire.

It is a quagmire, first, because the boy is gay and a newspaper has misrepresented an article Charles once wrote to suggest he is anti-gay. That is not true, and the newspaper offers to correct the error, but, as his lawyer, Richard (Jordan Lage), explains mostly nonsensically, Charles must also write some sort of paean to the newspaper’s power in order to get this correction. “Their bet is: Do you want to go to court, against their battery of lawyers, and unlimited wealth, and have them drag it out forever?” Richard asks Charles, referring to no currently extant newspaper publisher.

It is next a quagmire because no one in this play, other than Charles, understands the concept of patient-doctor confidentiality. In an escalating series of hypotheticals that may or may not then turn real, the boy’s defense attorneys demand first Charles’s testimony and then his patient notes. Richard, his lawyer, behaving more as a prosecutor, assures him that he will be forced to comply with the state (which has somehow become an agent for the defense). His wife, Kath, the unfortunately dense character played by the unfortunately accented Pidgeon, seems to have no idea that she’s married to a doctor, or what that entails. She doesn’t understahnd. “Drop all this f—king nonsense,” she shrieks at his when he won’t testify, and when apparently her friends won’t talk to her because of it. “Drop it. Make your statement. Go to the court. Say what they want. Give them whatever they want.” Psychiatrist, meet collaborationist.

Finally it is a quagmire because of Judaism. Charles has had what you might call a crisis of rationality because of these murders; he has perhaps given up on the idea of psychology, and he has turned to faith. He has started reading the Bible, returned to the more observant Judaism of his youth. The second act — “The Penitent” runs a brisk 80 minutes or so, and that includes an intermission — opens with a stylish scene of cross-examination, Charles testifying under the questioning of opposing counsel (Lawrence Gilliard Jr.), called only Attorney.

Charles tells the Attorney that he believes the Bible is at least divinely inspired, if not necessarily the precise word of God, and that it contains wisdom. He is of course confronted with the Leviticus man-who-lies-with-a-man business, and he replies that Biblical law must be interpreted. This is all actually entirely reasonable. A man of science and rationality, confronted with a shocking challenge to his beliefs, might well return to the religion of his youth for solace and inspiration. He might well believe that the Bible is divinely inspired and contains wisdom, which is not the same as turning fundamentalist. He might also believe it is wrong about some things. This is not inconsistent, except to the Attorney, scripted by a dramaturgical Antonin Scalia.

There are further turns, absurd but obvious plot points I won’t spoil that dig Charles deeper into his quagmire. But, like the debates over libel law and state power and Biblical law, they are all sleights of hand, all inauthentic excuses to set up arguments. Ultimately, it seems, Mamet’s goal is an indictment of the well-intentioned good liberal, blind to the controlling power of the press, the state, and religion. But it’s a poorly litigated case.

*Jesse Oxfeld has written about theater for New York Magazine, Entertainment Weekly and Town & Country. Follow him on Twitter, @joxfeld