Meet The New Star Of ‘The Band’s Visit’ (Same As The Old Star)

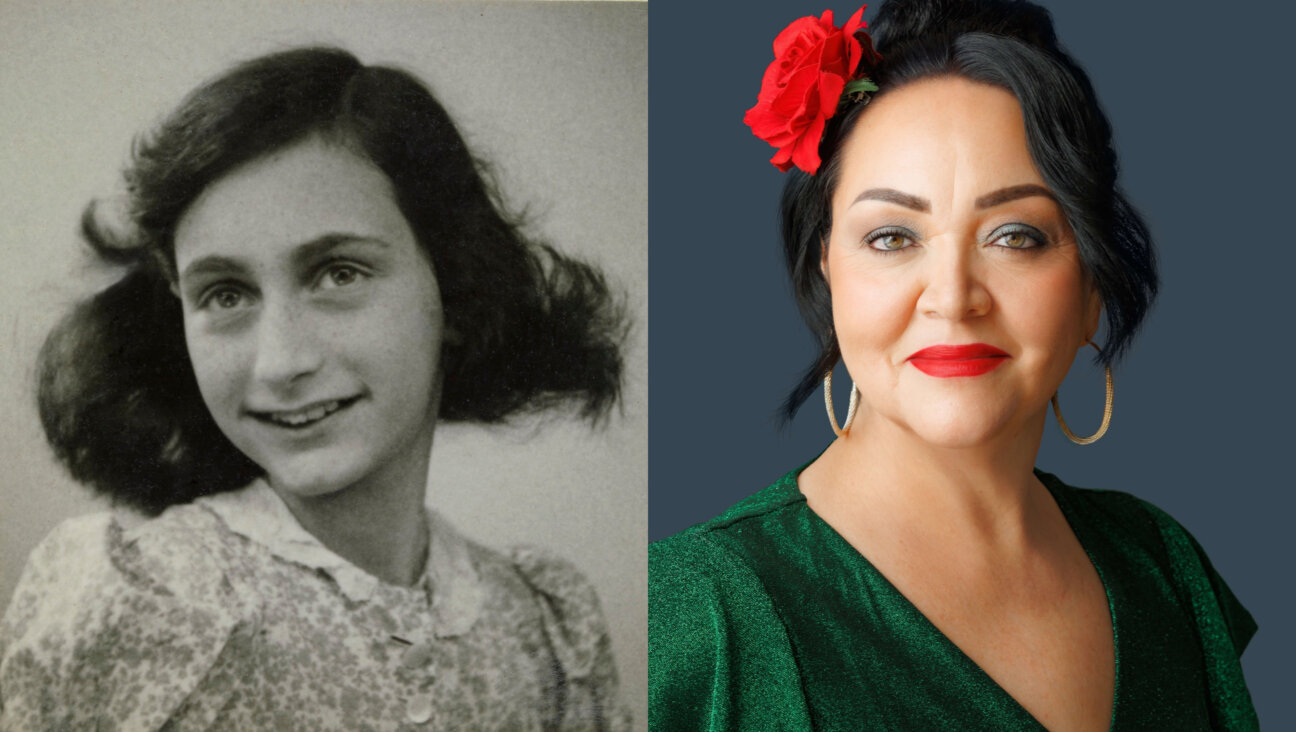

Katrina Lenk and Sasson Gabay in “The Band’s Visit.” Image by Evan Zimmerman

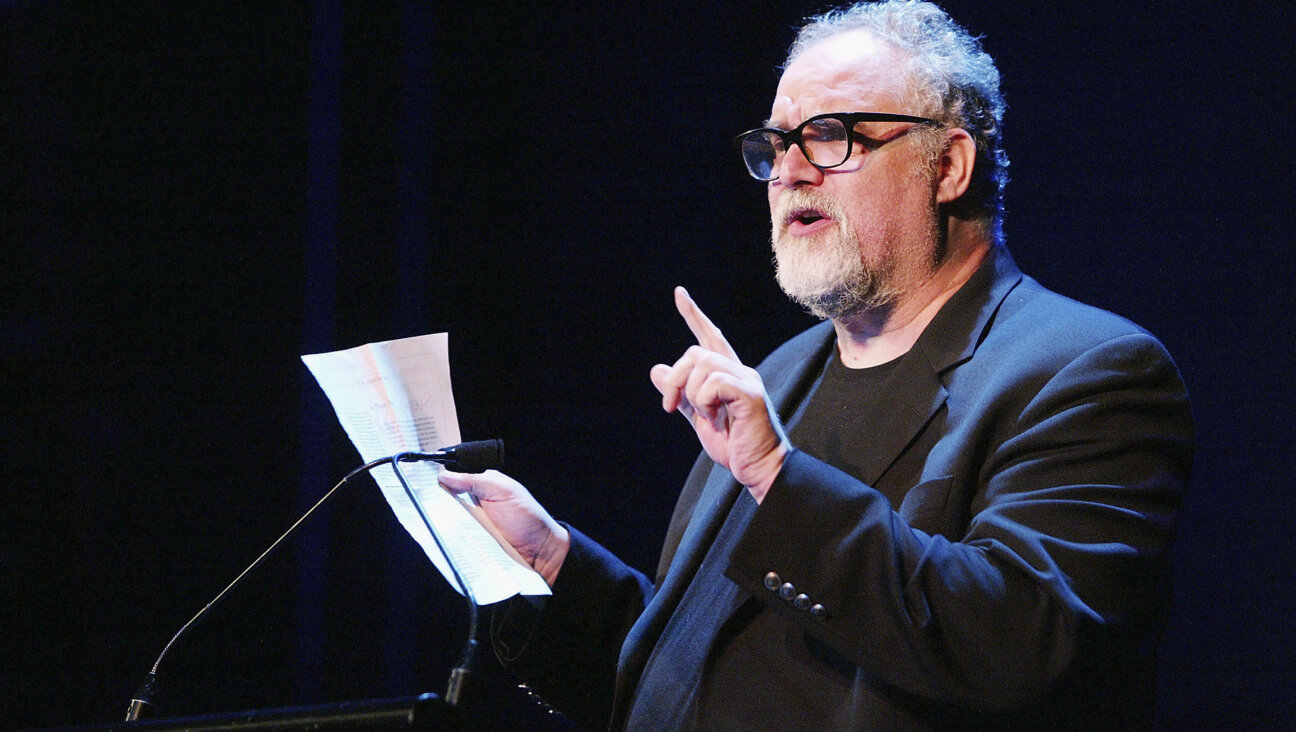

For Sasson Gabay, 71, acting is second nature, not unlike eating, drinking or even breathing. He instinctively observes the people around him, the way they interact and behave. It’s all source material, culled and stored for future roles that he might play.

“I look at you, how you speak, the kind of questions you ask, and think about how I might use what I see later,” he told me as we sat on a couch, sipping water from large goblets in his dressing room at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre.

It was a few days after the Israeli actor, a star in his own country, made his Broadway debut replacing Tony Shalhoub in the multi-Tony Award winning musical “The Band’s Visit” and, in an odd turn of events, reprising the role he (Gabay) originated in Eran Kolirin’s 2007 film that inspired the musical. For his work in the film he walked off with the Ophir Award (Israeli equivalent to the Oscar) and the European Film Award.

Adapted for the stage by Itamar Moses with music and lyrics by David Yazbek, the haunting and lyrical musical touches on themes of longing, disappointment and reconciliation; it recounts what happens when the Alexandria Ceremonial Police Band headed to Petah Tikvah, slated to play at the Arab Cultural Center. The band gets lost, and the musicians find themselves stranded in Bet Hatikva, an outpost of an Israeli desert community.

The show is not plot heavy. In fact, little happens, but in the course of one night the characters lives change and small bridges are built, most pointedly between the Egyptian conductor, Tewfiq (Gabay), a stern and judgmental figure, and the world-weary Israeli restaurant owner, Dina (Katrina Lenk). The eroticism is there though the relationship is never fully realized, making it all the more poignant.

“Playing the role again, it’s like meeting an old friend or a younger brother,” said Gabay, who is palpably more relaxed than his formal onstage alter-ego. “He’s part of me, within me all the time. The film was a significant part of my life and very dear to me. It changed my career. It was also my connection to Ronit Elkabetz, who played Dina in the film. Elkabetz died of cancer in 2016. She was brilliant. But then so is Katrina. Ronit would have loved her performance.” In his Playbill bio, Gabay dedicates his performance to Elkabetz.

Gabay viewed a tape of the production before coming on board, though he did not see Shalhoub play the role onstage. Unlike many actors, he was not afraid to study another actor’s spin for fear that it might intrude on his own interpretation. On the contrary, it only enriches his own performance he said. Either way, he was the first to tackle the role and he’s also played it in Israeli theater. Still, in the 11 years that have passed since the film premiered, he believes his Tewfiq has grown. He has more breadth and maturity, and the rest is intangible. “When something is not working it’s easy to define. When it is working it’s difficult to say why.” * The Iraqi-born Jew of Ashkenazi descent plays Arab characters frequently; indeed, he can “pass,” and that’s not an issue in the Middle East. The emotionally fraught topic of ethnically correct, nontraditional or color-blind casting just doesn’t have the currency there as it does in the States, he said, adding that if people feel he has unfairly taken roles from Arabs they haven’t let him know about it. “One of the reasons I would hesitate about permanently relocating to the United States is that I probably would be typecast as an Arab, which means I would play a lot of terrorists and wouldn’t have a chance to play other characters,” he said.

Gabay. who has a one-year contract to perform in “The Band’s Visit,” is now living in New York with his wife, a children’s book writer. He felt comfortable making the move, because his five children are grown; his two youngest are about to begin their military service in Israel.

Asked if he’s conscious of himself as an Israeli among New York theater artists who may not be especially friendly to Israel, he said it’s inevitable for him to feel like the “other” and to experience a degree of tribalism, defining himself in equal measure as an Israeli, a Jew, a human being and an actor. “I don’t like many Israeli policies, and feel comfortable talking about it openly in New York,” he said. “But at the same time, I’m patriotic and feel obliged to explain the other side, what their views are and where they’re coming from. Obviously, I wouldn’t be feeling this in Israel.”

Gabay arrived in Israel when he was 3 years old, and he remembers nothing of Iraq. He first spoke a Jewish Iraqi dialect; his second language was Hebrew. His background was “traditional,” he said, which is equivalent to what we’d call “conservative.” But those distinctions and denominations are virtually meaningless in Israel, since the majority population is Jewish.

“Unlike the United States, you don’t have to practice your religion in order to maintain your identity,” he said. “I am not religious, but Jewishness is a part of me. And I have a deep appreciation of Jewish values: humanism, loving your neighbor as yourself, a compassionate relationship to immigrants and refugees. And we have to fight for these values now. It’s an issue in Israel, too, with the large number of African refugees who have been pouring into the country.”

* Thanks to weekly radio plays, including Shakespeare and modern works that he’d listen to each Saturday afternoon, Gabay had his sights set on a theater career by the time he was 11. The family didn’t own a TV at the time, and trips to the cinema were rare. Once Gabay played a small part in a school production, he was hooked.

“I felt at home, like a fish swimming in water,” he recalled. “I was a shy kid, so acting became my way to express myself. To this day it’s my way to express myself.”

After a mandatory tour of duty in the Israeli army, he studied theater at Tel Aviv University and launched his acting career in several of Israel’s better-known theaters, not least the Be’er Sheva Theater and Beit Lessin Theater. He has quite a range. He’s starred in “Servant of Two Masters,” “Catch 22” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” He has also performed in many languages. Interestingly, each language subtly and unconsciously alters his interpretation of the character. In Arabic his voice drops an octave or two. “I think it’s because I hear my father speaking it,” he said. “I hear his voice.” In Yiddish, which he learned for a role, his voice is higher and he doesn’t know why.

Despite a successful career in Israeli television and appearances in many Israeli and international films, and even an American blockbuster like “Rambo III,” he considers theater his favorite medium. “It’s my bread and butter,” he said. “That’s how most actors make a living in Israel. It’s not like here, where you can make one major film and be wealthy for the rest of your life.”

At the same time, it’s easier for actors to be employed in Israel, not least because there are fewer of them, so the competition is simply less keen. In the States, he said, for any one role you have at least 10 actors, all of whom are equally good, vying for the same part. In Israel it’s altogether less complicated than in America, where, for example, well-known actors frequently employ managers, publicists and lawyers in addition to agents. In Israel an actor may have one agent and producers can still reach many performers directly without the benefit of highly paid intermediaries.

Though most Israeli theaters continue to be publicly underwritten, government subsidies have diminished; 70% – 80% of the funding comes from ticket sales, “which means theaters are now producing [fewer] experimental and more commercial productions than they might have10 years ago. They have to appeal to the largest number of people.”

Looking back on his body of work, Gabay conceded that the most challenging roles in his career were those he didn’t connect to immediately, like Claudius and Cyrano, two characters that, curiously enough, he had dreamed about playing. He said it’s the classic case of “Be careful of what you wish for. “My biggest successes have been the surprises,” Gabay noted.

At the moment, his thoughts are focused on “The Band’s Visit.”

“Most plays and films are tributes to the strong, the courageous, the heroic,” he said. “This one is a tribute to ordinary people. The story grows slowly and gently. I hope audiences leave the theater feeling that everyone deserves a hug. You’re born, you’re a human being, you’re good enough. You’re entitled to get a hug and put a crown on your head.”

The New York audience has been an eye-opener. Comparing it with Israeli audiences that are not readily impressed and can be seen rushing out of the theater before the curtain calls are over, to get to the parking lot, he said: “Here, in New York, audiences come to enjoy a show; they respond so warmly to every joke. At the end, there are the standing ovations and I can see the faces glowing. And then they wait for you at the stage door for your autograph.”

He still can’t stop marveling at producer Orin Wolf’s enthusiasm for initiating the whole project, “for having the courage to turn a delicate, gentle film where nothing really happens into a play, and then on top of that turning it into a musical and then on top of that bringing it to Broadway and then on top of that having the courage to invite me to come and play Tewfiq,” he said. “It’s a terrific experience.”

Simi Horwitz won a 2017 Simon Rockower Award and National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Award for her Forward article “These Frum Filmmakers Are Revolutionizing Orthodox Cinema”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Cardinals are Catholic, not Jewish — so why do they all wear yarmulkes?

- 2

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 3

News School Israel trip turns ‘terrifying’ for LA students attacked by Israeli teens

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

Opinion This week proved it: Trump’s approach to antisemitism at Columbia is horribly ineffective

-

Yiddish קאָנצערט לכּבֿוד דעם ייִדישן שרײַבער און רעדאַקטאָר באָריס סאַנדלערConcert honoring Yiddish writer and editor Boris Sandler

דער בעל־שׂימחה האָט יאָרן לאַנג געדינט ווי דער רעדאַקטאָר פֿונעם ייִדישן פֿאָרווערטס.

-

Fast Forward Trump’s new pick for surgeon general blames the Nazis for pesticides on our food

-

Fast Forward Jewish feud over Trump escalates with open letter in The New York Times

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.