Zach Zucker wants to be a modern-day court jester

The comedian, with his alter ego Jack Tucker, is a nonstop entertainer

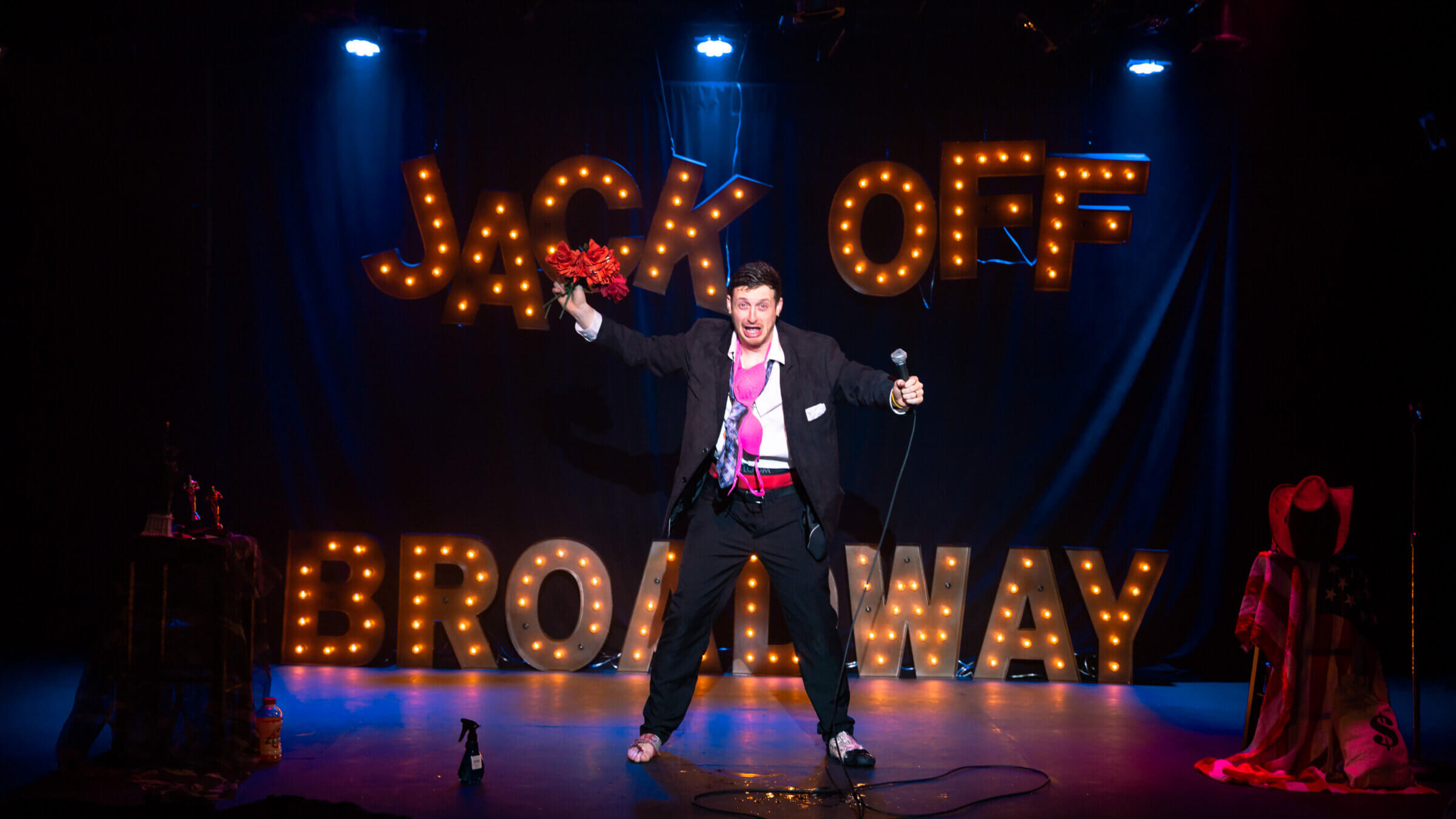

Zach Zucker as Jack Tucker, before he got new shoes. Photo by Dylan Woodley

Last April, amid his many travels, Zach Zucker lost a shoe. Then, this March, performing at South by Southwest in Austin, wearing the holey remnants of a McDonald’s-branded sock, he lost the other.

“Until two days ago I didn’t have any shoes,” said Zucker, who since 2017 has been performing as his standup alter ego Jack Tucker — the world’s worst comic. Tucker wouldn’t think to replace his footwear, so it became part of the act.

Zucker now pays homage to the time he hoofed it barefoot. In his act, he trips over his mic cord, sending one shoe flying upstage. At a recent performance at the SoHo Playhouse, it landed perfectly on lightbulb-lined letters that spell out “Jack Off Broadway.” The words lit up the instant the shoe dropped.

He appealed to the audience for praise for this minor miracle. He received it.

Zucker’s show, Jack Tucker: Comedy Standup Hour, playing through April 13, was made a New York Times Critic’s Pick the week before. Zucker wasted no time affixing a sticker with this accolade to every prop imaginable, including himself, who, in 70-odd minutes, rivals the punishing physicality of Buster Keaton and serves as a millennial answer to Andy Kaufman’s Tony Clifton.

Jack Tucker is better experienced than explained. He comes on stage already drenched in sweat. (Zucker used to stand in a kiddie pool backstage where he would be doused with seven pitchers of water — one freezing cold — until he was “just like a deer on Vyvanse.”) His cheap black suit is rumpled in Godotian fashion. The waistband of his red, Fruit of the Loom boxers flares out from his pants along with an orange starter pistol.

Instead of a pocket square, he has wads of $100 bills, which he litters on the ground. His pockets are a bottomless reservoir of condoms he strews like confetti. He used to wear a marathon medal (Zucker ran it in character), but it was blinding the audience. Now he just wears a sloppily knotted tie — the first tie Zucker’s dad ever gave him.

Tucker’s material is a mix of a malfunctioning shock jock soundboard, Adult Swim anarchy and whatever Jim Breuer is doing these days. The catchphrase “I’m just jacking off” gets prolific use, along with his compulsive gestures to his wedding band and a hacky glance at his palm to remind him what city he’s playing.

He spits a disgusting amount, spills entire cups of beer. At one moment he shoves the microphone back to his molars.

What he’s doing is pure clown.

Zucker, 30, is a graduate of the École Phillippe Gaulier, whose eponymous instructor, a legendary French clown, told him that the most important part of the clown costume is the shoes — it’s what connects you to the ground. Tucker needs no shoes.

“It just feels like this guy is this animal,” Zucker said.

Owing the audience

Out of character, Zucker is a connoisseur of streetwear, sporting a powder blue Kith hoodie. He has a stubbly beard, earrings, a silver chain necklace (and corresponding bracelet). Under the hoodie is a beige tee, fashionably oversized.

Meeting at a coffee shop near the SoHo Playhouse, he orders a tea — help for his voice.

“My shoulders are banged up, my knees are banged up, my voice is all banged, but we have to keep doing this,” Zucker said.

What he does changes. Though he’s toured the show for five years it’s never been properly locked down. At the Thursday performance where his shoe alit perfectly on the upstage letters, he hardly got through most of the planned material.

A few things took him off script. Two women left to use the restroom and Tucker engaged, forcing them into a pinky promise to return. (They did.) Doing crowd work he found someone in the front row named Meg, prompting him and his director Jonny Woolley, who co-created the character and supplies frequent live sound effects, to play through the Family Guy theme multiple times. (Meg Griffin is a character on Family Guy; Tucker also does an inept impression of her baby brother, Stewie.)

“I owe the audience,” Zucker said at the coffee shop. “I have to give them a good show. But I don’t believe that a good show means doing the exact show.”

On the night of the miracle shoe, Jesse Eisenberg was in the crowd. Zucker read a text the actor sent to Woolley.

“Your show is probably the best thing I’ve ever seen in my life. It felt like the kind of thing you still talk about seeing 20 years later.”

Not everyone’s a fan. Some audience members, possibly following the guidance of the Critic’s Pick, have left the theater. Zucker says that’s no major loss.

“This is a 178 seater,” Zucker said. “If we get 170 people on board, two to four people leave and four people are visibly not enjoying it and everyone else is f—ing loving it — that’s my dream crowd. ’Cause then the people who don’t like it only get more upset when everyone else is laughing.”

Rockin’ the Jewish suburbs

Zucker — possibly like Tucker, who speaks with an interborough twang — was born in New York and spent most of his childhood in what he calls the “Jewish suburbs of Chicago.”

“Growing up in Highland Park, and at summer camp, Zach was always the coolest kid everywhere we went,” said Zucker’s brother, David, four years younger. “He definitely was not a performer, at least in a traditional sense.”

Zucker didn’t act — though he did act up.

“He was kind of a misbehaving, Hebrew school delinquent,” David Zucker remembers.

“Then he found a rabbi with a more personalized approach and that was ultimately who he went forward with to become a bar mitzvah.”

Zucker was a class clown. He admits to being a fixture of the principal’s office and someone on good terms with his high school’s security guards (Zucker shouts out a few — Terry, Louie, Big John, Jumbo, “the whole squad”).

Tall and wiry, he was a “sports boy,” playing baseball and basketball. David Zucker said he might have played Division III.

“I was always a look-good-to-play-good athlete — definitely early stage bisexuality,” Zach Zucker said. He now regards his uniform and his equipment as costumes and props. His sporting past is evident when Jack Tucker bats an apple with his microphone or catches a hot dog in a bun from 100 feet away.

Zucker was a devotee of disruptive, destructively dumb comedy like Jackass, South Park and Da Ali G Show. He took an acting class junior year for an easy A. When he was a senior, taking Acting 3, his drama teacher told him to check out Second City, the improv mecca in Chicago.

Zach, with a middle school-aged David, went to see the show Spoiler Alert: Everybody Dies with Sam Richardson and Tim Robinson, who’d go on to create Comedy Central’s Detroiters and collaborate on Netflix’s cult sketch hit I Think You Should Leave.

The brothers’ minds were blown. They immediately signed up for teen classes. Zucker started in the middle of basketball season and ended up quitting the team his senior year — he found a more supportive community among performers.

“His first ever play that he ever did in high school was his last ever,” David Zucker said, of a 10-minute short play where Zach played a Ken doll. “That was really the only time I ever saw him act until he decided to become a professional.”

Varsity athlete to clown college

David Zucker thought his big brother might go to a Big Ten school like his friends. Instead he surprised everyone by moving to Los Angeles to take sketch and acting classes and intern at the Upright Citizens Brigade.

While he was preparing to interview with Sacha Baron Cohen’s production company, Phillippe Gaulier was in town leading workshops. Zucker knew Baron Cohen studied with him and enrolled to impress the boss. He got the Baron Cohen job, but after a few months decided to leave for a two-year program at the École Gaulier.

Instead of finishing college, he went to clown school. How did his Jewish family react?

“It was definitely not good,” Zucker said. “I went from being the golden grandson to being the black sheep — to being the Zach sheep of the family very, very quickly.” (Now they get it, or at least accept it. His grandparents Facetimed in for opening night at the SoHo Playhouse.)

At Gaulier, Zucker studied Greek tragedy, mask, melodrama and Shakespeare. The second year was split between 10 weeks of clown, vaudeville and Bouffon, a style of clowning that centers on mockery, exemplified by characters like Borat.

Through Bouffon specifically, Zucker taps into something fundamentally, though not exclusively, Jewish.

“You as the oppressed play the bastards that oppressed you and you mock them to the point they go home and kill themselves, whether it’s metaphorically or literally,” Zucker explained, and referenced Baron Cohen. “That’s Sacha doing the song ‘Throw the Jew Down the Well.’ You give everyone the rope to hang themselves with.”

With Tucker, the target doesn’t seem to be the audience so much as it is an entire genre of boorish standup — and the industry executives that he said “wouldn’t know good art if it hit ’em in the f—ing face.”

At Gaulier, Zach met a Norwegian student named Viggo Venn. They became a stage duo, performing physical comedy in spandex superhero suits as “Zach and Viggo.” Venn recently won Britain’s Got Talent as a solo act, but there was a time when he and Zucker had trouble getting booked.

It was from this frustration that Jack Tucker was born.

Laughing at absolutely nothing

Zucker jokes that he is the one Jew who can’t make it in Hollywood. So maybe it’s unsurprising that his way around this dilemma was performing as a perpetually sodden gentile.

Bookers told him what he was doing wasn’t comedy, and he was annoyed by who was getting gigs. Often it was bro-y comedians making lewd jokes about women.

“The bad comedian’s getting booked, so let me be a bad comic,” Zucker reasoned.

“The name Jack Tucker — it was the first thing suggested,” said Dylan Woodley, who helped co-create Tucker, and now performs in his pre-show as a headbanger on rollerskates, relishing yacht rock and the Baha Men.

Many of the early jokes they devised remain in the show, but new lore and bits are developed constantly. There are now remote control rats that skitter around the theater and an interruption, inspired by a viral protest at Enemy of the People, where two self-serious climate activists and “theater artists” devolve into frenzied kissing.

Tucker’s offstage life is vague. He may live in a closet above a noodle shop in Chinatown, eating rotten noodles until he gets “noodle noggin” and hallucinates. His friends are the Ninja Turtles and his rubber chicken. He might show up from gig to gig in the bottom of a waterlogged shipping container. The exact biography, like the dramaturgy of the play, is up for grabs.

“I’m not sure we’ve actually gone through the show proper this whole run,” Woodley said. “Every now and then Zach will decide ‘OK, I’ll touch upon the script,’ and he’ll say a line and move it forward ever so slightly, but he just has another detour, another idea in his head.”

Comedian Natalie Palamides, who met Zucker over a decade ago at UCB, said that he is embracing a key tenet of clowning: playing the moment and letting go of what you’ve prepared.

“He’s super tuned in to listening to what the audience wants and he will play a game out,” Palamides, whose show Nate — A One Man Show is streaming on Netflix, said. “He will beat it over its head and come up with a million different ways to do that same game and keep the audience laughing.”

The game can be hard to describe. At a recent performance, Tucker started coughing. It got a reaction, and so he continued clearing his throat, looking visibly uncomfortable from the neck up while, with the rest of his body, he perfectly executed hip-hop dances like the Nae Nae.

“He has an uncanny ability to make people laugh at absolutely nothing,” Palamides said. “Like there’s nothing going on, and he can get a laugh. I have no idea how he does it. I think it’s just because he’s having fun up there.”

A modern day circus

On a Tuesday night at the Bell House in Gowanus, Zach Zucker is taking a night off from Jack Tucker: Standup Comedy Hour to do Stamptown, his long-running variety show. Alone onstage in a dark hoodie, he dances to “Houston” by Cico P and “Grey Area” by 2 Chainz, as a mostly millennial crowd files in. (This is Zucker’s music; Tucker’s is heavier on blithe bravura: Ricky Martin’s “Livin’ La Vida Loca” and Rascal Flatts’ “Life is a Highway.”)

Between freestyles, he hops offstage, hugging people he knows, checking in on the tech. He loves to play host, but he hosts the show proper in character as Tucker.

Stamptown the show, named for Étampes, the village where the École Gaulier is based, began in Australia in 2017. Now it mostly plays wherever Zucker happens to be — he pays rent in Los Angeles, but he’s often in Europe and wants to settle in New York.

“I don’t want standup,” Zucker said of his programming. “I want burlesque, I want clown, I want magic, I want dance. I want to see a guy playing trumpet on the street and get him to come in and do something. We got SpongeBob from Hollywood Boulevard.”

David Zucker calls his brother’s operation a “modern day circus.”

Electric. I want to inject this show into my eyes on prescription. If you think that sounds weird, you’ve not seen this show/these performers. Bonkers. @stamptown_ sold out at @sohotheatre this weekend otherwise I’d be back for round 3&4. Best of the best. pic.twitter.com/yLoFnnYBfL

— Harry Bower (@HarryBower_) January 26, 2024

Stamptown’s ethos is, “Do what you’ve always wanted to and do what you feel like you can’t do anywhere else.”

At the Bell House that meant burlesque performer Gigi Holliday (who spanked a very game Tucker), singer Caitlin Cook’s songs written from bathroom stall graffiti and a running gag where people in blue morph suits fell out from the wings dead every time a gunshot sound effect came from the booth. (At one point the stage looked like Act V of Hamlet.)

In between acts, Zucker somehow keeps up his stamina. Palamides wishes he could take some of the pressure off himself.

“He’s just always run ragged from doing like every single job that Stamptown requires him to do,” Palamides said. “He just is the most insane one-man band you could ever have the pleasure of witnessing and I implore him to get a producer.’”

Woodley thinks that performing is what keeps Zucker going.

“We can almost see the light fade from his eyes as we go into too many weeks without getting him on stage,” Woodley said. “That connection with the audience is something that’s really, really so important to him.”

That connection comes from Gaulier, who teaches that the performer’s job is to be “a blank screen to dream around.” It’s not about how the actor feels; it’s about the crowd.

Zucker is a born people-pleaser, but his ambitions make it difficult to satisfy himself.

He wants to dance at the Super Bowl (he has a dance agent), to be a background extra who walks into walls. He’s confided in Palamides that he doesn’t just want to sell a TV show — he wants to run a network. She thinks if anyone could, it’s him.

“To be like a modern day court jester would be my dream,” Zucker said. “I want to do the White House Correspondents’ dinner, I want to host some awards, I want to be able to say things to the people that would be scary and fun to say. Someone’s gotta do it, and I wanna be the one to do it.”