A century-old Jewish tale of demonic possession — yet one that’s just as relevant today

Igor Golyak reimagines ‘The Dybbuk’ for the 21st Century

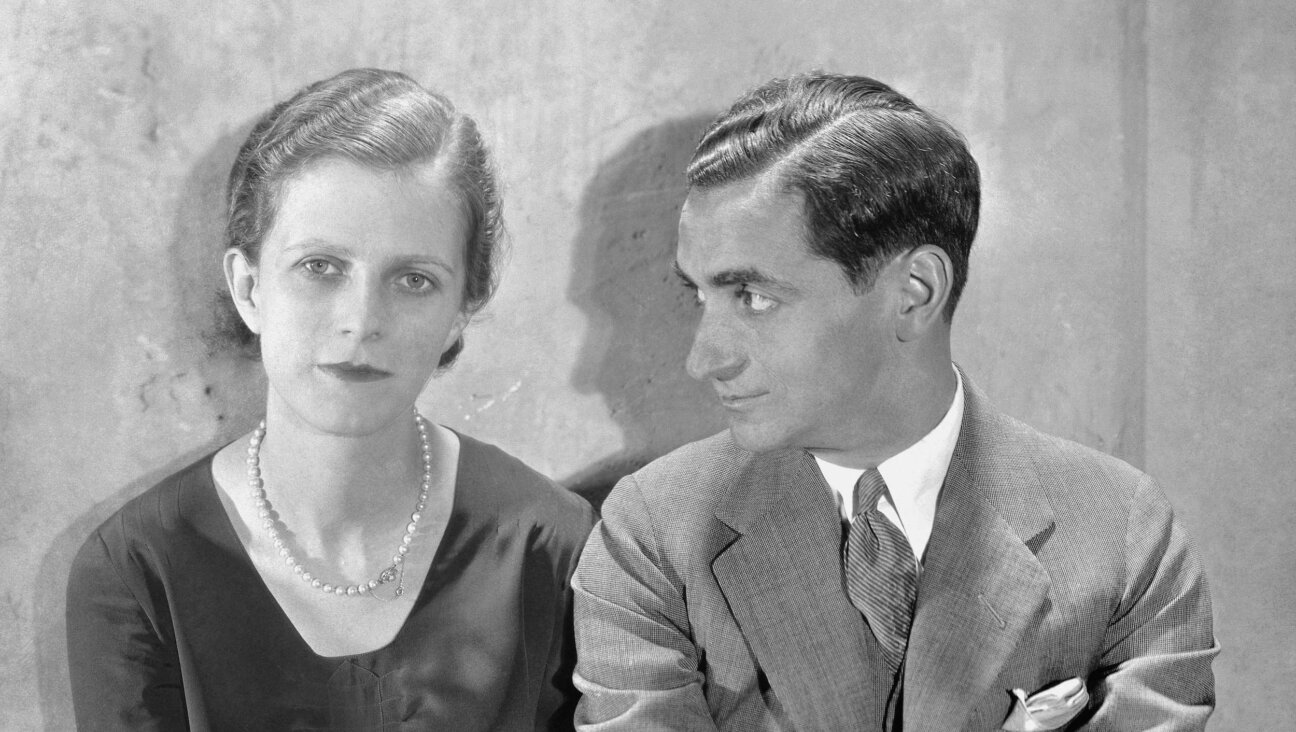

Yana Gladkikh plays Leah in ‘The Dybbuk.’ Photo by Andrey Maslov

“Anything you do needs to speak to the people of today,” Igor Golyak, the artistic director at the Arlekin Players Theatre company in Needham, Mass., told me.

“I don’t know how to do a play without modernizing it.” he said. “If a play is done without modernizing it, it means it’s a museum piece. And then it’s irrelevant to the people’s lives today.”

Right now, Golyak. who founded Arlekin in 2010, is directing a play he also co-adapted, at Vilna Shul in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. It’s an intimate, confrontational, supernatural and highly physical version of The Dybbuk, a play S. Ansky wrote between 1913 and 1915, based on the familiar, titular figure — a supernatural creature from Jewish folklore who, caught in a state of limbo, seeks refuge by attaching itself to the soul of a living person. (Usually, the dybbuk is male and attaches itself to a woman.) Ansky’s play was first performed in Yiddish in Warsaw in 1920.

“When it was created it was very much like any play by Chekhov or Shakespeare,” Golyak told me over the phone two days after opening night. “It made a revolution of some sort and [it’s about] how you translate the essence of that revolution to today’s world.”

Yet, when you walk into the second-floor performance space, it’s like a time warp. You’re immersed in this old world, a shtetl perhaps, one populated by long ago and faraway characters who are very much present in the here and now. And, at times, literally in your face.

Golyak, who The New York Times recently called “among the most inventive directors working in the United States,” first encountered The Dybbuk when he was studying at the Schukin Theatre Institute in Moscow. But the idea for this version, which he co-adapted with Dr. Rachel Merrill Moss, came to him about a year and half ago when he visited the Vilna Shul, which was built as an Orthodox synagogue in 1919 primarily by Lithuania immigrants. It was repurposed as Boston’s Center for Jewish Culture in the 1980s.

“It seemed to me, first of all very mystical,” Golyak said of the site. “It doesn’t function as a synagogue anymore but it has a sense of time, of this forgotten world and I think it suits the play very well. I have a bunch of plays I keep in my back pocket and then things just come up and tell me when they want to be performed.”

The Dybbuk is a story of star-crossed lovers who seem to occupy various levels of life, death and the netherworld. It is a busy and physically demanding work that starts with the ominous, distant sound of dripping water, followed by electric flashes of light and a sonic cacophony.

Members of the audience sit in pews abutting the long sides of the rectangular performance space. The set is often cloaked in haze; the smell of burning sage wafts through the room during an exorcism scene.

There are two stages, one smallish and semi-circular and the other comprising two decks of scaffolding, sometimes covered with a diaphanous plastic. I wondered if it was part of the ongoing renovation at Vilna. Golyak said it was not — it was built for the show — but he loved the thought that it might have been: “That’s actually a great compliment because it’s important, especially with site- specific work, that the space dictates what needs to be in there, that it seems like it’s just a part of the environment,” he said.

Khonen and Leah are the central characters, but family members circle them constantly, advising, consoling, cajoling and squabbling. Are they alive? Dead? Neither? Our perception of them shifts during the play.

“That’s very conscious,” Golyak said, of the varying takes, “but all of these characters are dead. It’s a remembrance of a life that has passed and of people that have passed.”

The actors utilize every bit of the space, often frantically darting this way and that, occasionally breaking the fourth wall. (Andrey Burkovskiy, an actor who was born in Russia and plays Khonen, one of the star-crossed lovers, tossed a bucket of non-existent water on me early on and patted my head.)

“It is really difficult,” Yana Gladkikh, a Russian-born actor who plays the other lover, Leah, told me over the phone about the production. “Because we’re running the whole show, and this construction is metal so whenever you accidentally trip and fall it causes damage. It all happened before the opening show but on the opening night it was like we’re flying through the stage effortlessly.”

Gladkikh considers Leah the most enjoyable and multi-dimensional role she’s ever had. “This role somehow contains everything,” she told me. “She’s a child, she’s very playful, she’s a free spirit, she’s very passionate, she’s a little devil, she’s a young woman who loves, who wants to experience all colors of life and love. There’s a lot of rage inside, a lot of pain, a lot of joy.”

Some of that joy is on display in a surprising instrumental Euro-pop track that plays as Leah and Khonen disco dance, bringing smiles and laughter among the audience. “We change the song from night to night,” said Golyak.

“That’s our favorite moment,” said Gladkikh. “We want to give the feeling that they are happy with each other, that they are regular kids.”

“It’s an emotional rollercoaster,” she added. “Leah is a free spirit who is locked in a certain box of a culture specific thing for the Jewish community and has her father’s expectations. She’s the one who has so much inside of her that she doesn’t have a chance to unleash her emotions and desires.”

When Golyak first started out, he told me, he didn’t want to identify as a Jewish playwright.

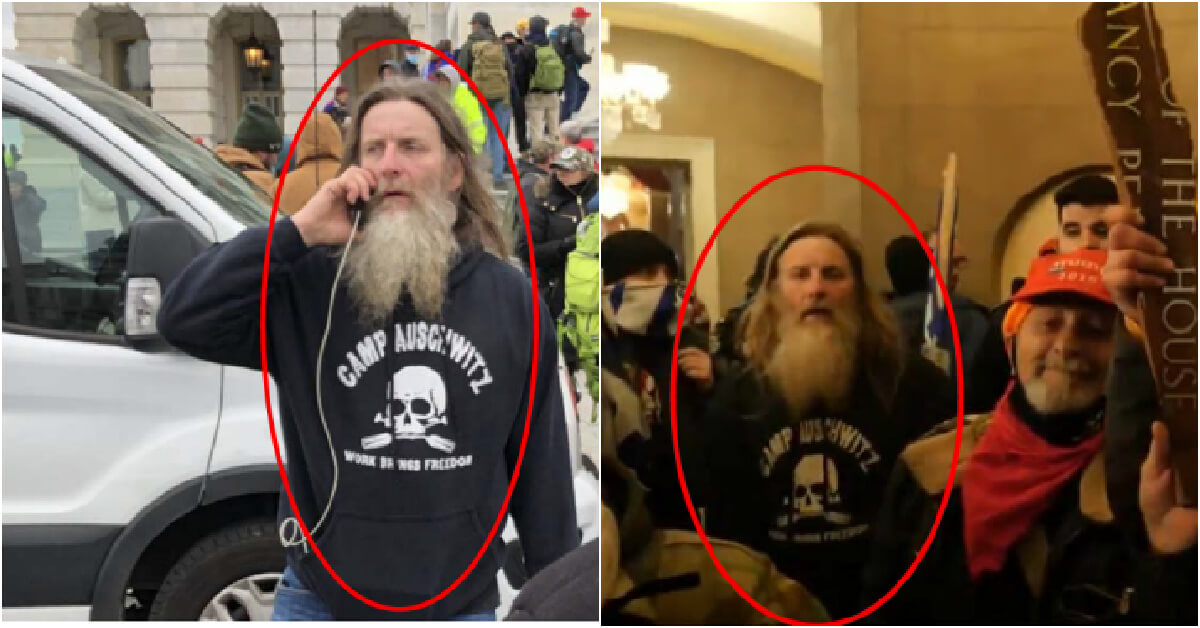

“Absolutely not,” he said. “There has been a change. It’s necessary to tell the story of the Jewish people and to remind people what our people have lived through and continue to live through. We’re in the same boat. Nothing has changed. Where we live has changed. Throughout history, we feel comfortable in one place until we don’t and they come to get us. That’s what helped me recognize my Jewish identity.”

In fact, Golyak, who is now 45, says he didn’t even know he was Jewish until his parents told him when he was eight. “I didn’t know the word existed,” he said. “I had no idea what that meant. It was not something that was spoken of. And since then, I have been trying to figure out what that means and the rise of antisemitism in the world helps me understand that, what it means to be Jewish.”

Gladkikh, who emigrated from Russia less than a year ago and is not Jewish, said that part of her journey was learning about Jewish culture. “We talked about it a lot when we were making this play because I’m not from a Jewish community and I learned a lot,” she said. “It was so interesting to dive into this whole thing.”

Gladkikh said that even as Khonen and Leah meet up at play’s end, “as I understand it, there is no happy ending because while they are perfect for each other, they can never be together, even after death. The tragedy is they did everything they could do to be together; they even crossed the border and blurred the lines between life and death so they could find each other. For me, it’s about the never-ending search for your loved one. Even if you are together and you love a person, you actually can never reach the essence of the person. Always two separate creatures. And that’s the tragedy and the joy.”

The Dybbuk plays at Vilna Shul through June 30. Afterwards, Golyak has hopes to stage the play in New York.