A visionary theater maker never thought he’d be ‘Jewish director’ — then the times demanded it

With ‘Our Class,’ virtual theater innovator Igor Golyak takes on the raw topic of antisemitism

Director Igor Golyak, known for his bold, tech-forward productions, is debuting a very Jewish season. Photo by Irina Danilova

When Igor Golyak was around 7 or 8, and his parents were filing paperwork to move the family from Kyiv to the United States, his father told him something he didn’t know about himself. In the bathroom shaving, he turned to his son, who was standing in the hallway, and said: “By the way, you’re Jewish.”

“I’d never heard of Jews,” Golyak, a theater director known for his bold use of new technology, recalled thinking; in the Soviet Union, the state suppressed Jewish practice and identity. “I’m still trying to figure that out. I don’t know what that means.”

Golyak, 44, reclining across two chairs in a rehearsal space on 42nd Street in Manhattan, had just finished a day of rehearsals for Our Class, Tadeusz Słobodzianek’s 2009 play about Polish classmates, Catholic and Jewish, who, during the Nazi occupation, find their lives upended by betrayals, massacres and immigration.

Golyak is an immigrant — a refugee really — from what is now Ukraine but was the Soviet Union when he was growing up. He says he is “somewhat Ukrainian” and, having moved to the Boston area in 1990 at age 11 and staying through high school there, also American. He studied theater in Moscow, and so is deeply influenced by Russian culture, as evidenced by his inventive riffs on Anton Chekhov — including imagining the great dramatist’s desktop computer and adapting The Cherry Orchard with a giant robot arm. More recently, Golyak’s Jewishness has become a predominant part of his identity and his art, but he is still struggling to understand it.

“What I do understand is this urgent feeling of being protective and just kind of learning about the Jewish displacement throughout time,” Golyak said, noting his concern for his two children, Jacob and Esther. “It never stopped, and I don’t know if it ever will.”

Golyak announced the season for his company, the Needham, Massachusetts-based Arlekin Players, in September, well before the Oct. 7 attack on Israel and subsequent war in Gaza, but its themes are timely. Our Class will debut at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Jan. 12, followed by a new production of Arlekin’s hybrid live and virtual production Witness, about antisemitism and the ship St. Louis, and a site-specific production of S. Ansky’s The Dybbuk, which will debut at the Vilna Shul in Boston.

“I never thought that I would be a Jewish theater director,” Golyak said, noting that his company, founded by immigrants, most of them Jewish, from the former USSR, is becoming increasingly Jewish-focused. “Fortunately, or unfortunately, it’s just kind of due to the time that we’re in and that’s just where we landed, responding to what we feel is important right now and what we feel passionate about.”

Golyak’s choice of work has been prescient before. During a production of The Orchard, a piece about a disappearing Russian world, Russia invaded Ukraine. During the run of Witness, the work he conceived about immigration and antisemitism, a gunman entered a synagogue and the American Jewish community held its breath.

“He says he doesn’t want to be right,” Rimma Gluzman, a member of Arlekin’s acting company and the chair of its board of directors, said of Golyak’s foresight. “He actually would prefer to be wrong.”

At the same time, Gluzman said, she thinks Golyak can only pursue projects that come from “places of pain and places of importance.”

Creating a common language

In 2018, Arlekin was staging We-Us, a documentary theater piece based on hundreds of interviews with Russian immigrants from the Boston area. Golyak wanted to set the play amid a baggage claim area. He found a real luggage carousel in Rhode Island and was determined to haul it up to the second floor of his black box theater — the theatrical equivalent, perhaps, of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo.

“Everybody was against it,” said Gluzman. But Golyak “doesn’t take no for an answer.”

For Golyak, it wasn’t enough to bring the conveyor belt up the stairs (he did). When Gluzman mentioned she had friends who worked for Massachusetts’ transit authority, Golyak insisted she call them to get authentic scenery for the play. They went to Logan Airport to collect signs and stanchions. The carousel was a visual metaphor for having arrived in America, but existing in a kind of limbo.

One day after the show had closed, Sara Stackhouse, then chair of theater at the Boston Conservatory and now Arlekin’s creative producer, raised doubts about whether she could help Golyak’s company. Golyak took her aside and told her about the production as a way of explaining himself.

“What he said is, ‘Sara, this is where we live,’” said Stackhouse. “‘We’ve left but we haven’t arrived. We’re here, but we’re waiting, then the baggage claim is happening and we’re waiting for our valuables and some of them never come. And the ones that come don’t mean anything here.’”

When Golyak returned to America in 2004, after studying at the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts and the Shchukin Theatre Institute, he couldn’t find work as a director in mainstream theater. He sold ads for the Yellow Pages and later mortgages, and was quite successful, but in his community he gained a reputation for giving feedback to his artist friends.

In 2009, Golyak started teaching acting classes to other Russian-speaking immigrants. The classes soon spawned productions, noted for their blend of dance, spoken word and music. Most of the plays were in Russian and the company performed their adaptation of Chekhov’s The Bear regionally and at the Moscow Art Theatre School. Arlekin, the Russian name for “Harlequin,” started to gain international recognition, and Golyak worked hard to court big names from Europe’s theater world to design sets and write music for the plays. In 2016, Arlekin built a permanent home on the second floor of a squat office building in Needham, where the immigrant community embraced them. But they hadn’t yet broken through to a general audience.

In 2017, when Golyak’s resume landed on Stackhouse’s desk at the Boston Conservatory for a teaching position, she didn’t recognize any of his credits.

“I put him in the ‘No’ pile,” Stackhouse said. “And then I thought about it, and was like, ‘That’s a self-made person.’” She brought him in for an interview and to lead an acting class.

Stackhouse remembers Golyak being incredibly charismatic and eerily still in his interview. She wasn’t sure about him until the conservatory’s teachers returned from Golyak’s trial lesson, raving about his technique. She hired him for the 2017 and 2018 school year and he started visiting her office — socially, but with questions about how the American theater worked.

When Golyak asked Stackhouse to meet with Arlekin, she initially declined. She had been executive producer of a theater company, The Actors’ Shakespeare Project, for over a decade, and didn’t want to involve herself in another. Golyak convinced her to see a show, an adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov, and she nearly drove past the unassuming theater. Once inside she put in an earpiece — Golyak was translating the production live.

“It was the best play I had seen in 10 years,” Stackhouse said. The production, Dead Man’s Diary, won Arlekin its first Eliot Norton award from the Boston Theater Critics Association.

Soon, Stackhose was going up the purple staircase, above what looked like an H&R Block or dentist’s office, drinking vodka with the ensemble and drawing up a strategic plan. Then the pandemic hit. With in-person theater out of commission, Golyak found his opening.

In May 2020, Golyak and his then-partner Darya Denisova staged a show from his living room, State vs. Natasha Banina, about an orphan girl on trial for a crime of passion. The show distinguished itself from other Zoom productions by weaving in video effects, like virtual cigarette smoke, and having Denisova interact directly with the audience watching from their homes. The Zoom chat was the jury and could change the outcome.

“All the major theaters across the world are shuttering and talking about how it’s impossible and like, there’s Igor with like a shoelace and an eggbeater making this brilliant thing,” said Stackhouse, who, after watching the show and seeing it earn a New York Times Critic’s Pick, committed to formally joining Arlekin and taking the production on a virtual tour of established theaters, elevating Arlekin’s profile beyond the 50-seat black box in Needham.

Also watching from quarantine were ballet dancer and choreographer Mikhail Baryshnikov and actor Jessica Hecht.

“I was totally drawn in,” said Hecht. “I was drawn in by the aesthetic and the way in which he used technology, but also the performance was exquisite.”

Golyak and Hecht started speaking, leading to a collaboration on the virtual production Chekhov OS, and later The Orchard, both also with Baryshnikov. When Chekhov OS earned Golyak his second Critic’s Pick, Stackhouse remembers him telling her, “I have one question for you: How does America work?”

Stackhouse says she serves as a bridge for Arlekin to the broader American theater, but that Golyak’s own stubborn initiative is proof of the truism from Hamilton: “Immigrants, we get the job done.”

When Gluzman sees Golyak move to bigger stages, like BAM and the Baryshnikov Arts Center, she sees an “unbelievable American story.” His goal, she says, is to “transform American theater,” a vision most didn’t see in the early days, when Arlekin’s close-knit company was staying up all night making the costumes and painting sets.

Hecht, who also partnered with Golyak to bring theater therapy to Ukrainian refugees in Moldova with her refugee arts outreach organization the Campfire Project, sees a difference in his approach.

“He has a deep way of using everything he’s been through as a person and as an artist,” said Hecht. “It’s something people say a lot about immigrants: that there’s a common language that they use in whatever they do that appeals to our sense of comfort and humanity. That’s what he does with his theater: He tries to create a common language that goes beyond English, or Russian or technology or Ukrainian — he creates this other sort of universal language that really affects people.”

‘Tragedy can happen anywhere’

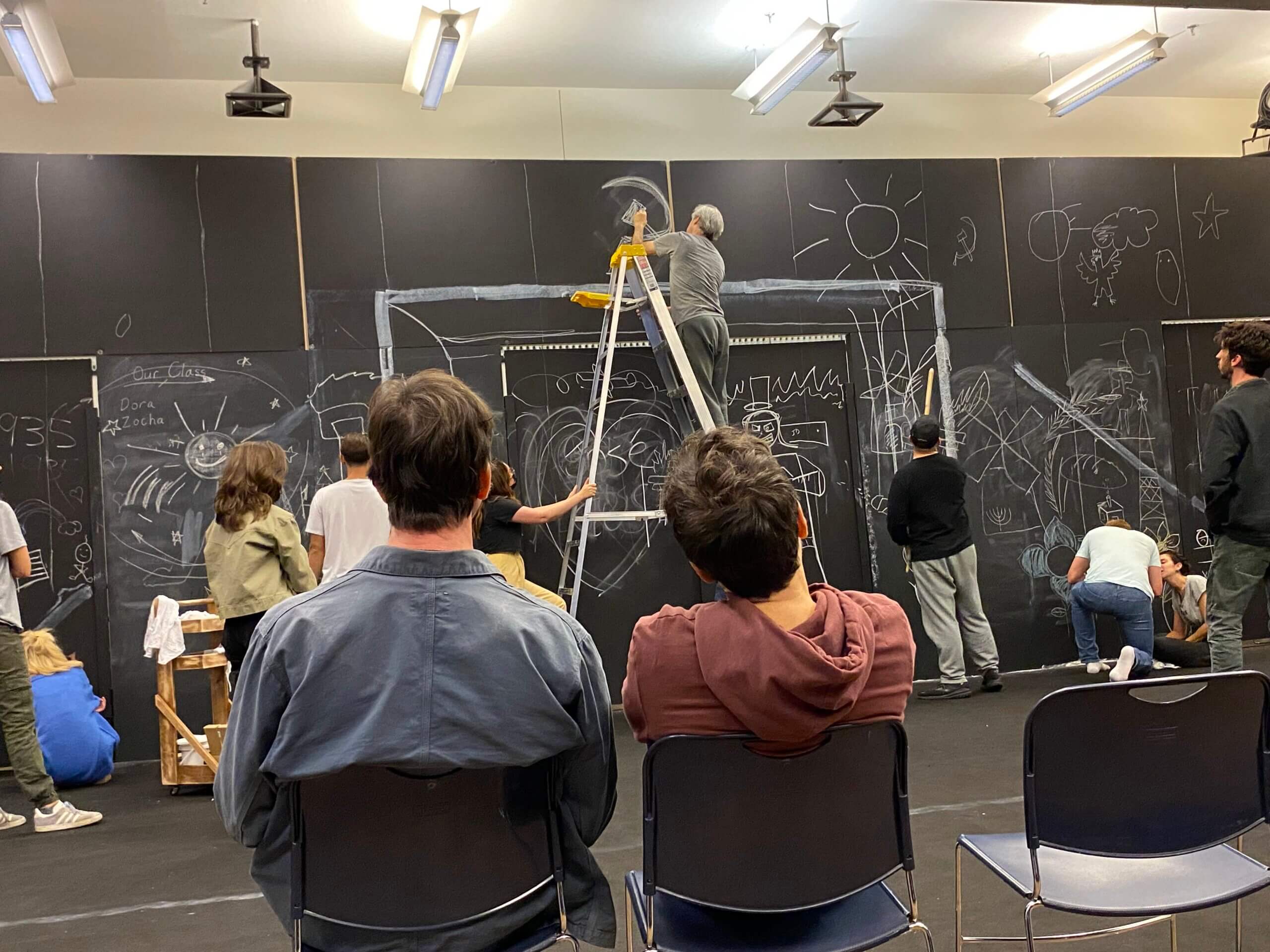

Golyak’s rehearsals for Our Class sometimes feel like a mix of playtime, group therapy and a tech demo.

On a cold Tuesday in December, actors practiced their chalk drawings on the back wall, designed by Jan Pappelbaum of the Schaubühne theater in Berlin. Richard Topol, playing the character of Abram, who leaves Poland for the U.S. to become a rabbi, scrawled Hebrew letters while training a portable camera at himself. On a flatscreen TV on wheels, Topol’s face appeared in close up. After a break, during which Golyak dribbled a prop soccer ball and troubleshooted some equipment, the cast read through a scene. Golyak asked guiding questions — what’s going on here? Where is your character in time and emotionally?

The ensemble for Our Class is made up of actors ranging from their 20s to middle-age. Most are American, but the company also includes a Ukrainian, Ilia Volok, and Andrey Burkovskiy, a former hockey player and film and TV star in Russia who left his home country when the war in Ukraine started. During the show, the cast fills the set with chalk symbols, like a Soviet hammer and sickle, replaced with a swastika when the Nazis invade. There are quotes from Lenin, a drawing of a grave for one of the dead classmates and, in cursive, the names of the 10 kids who start the play as innocents. By the time the play ends, some of these classmates will have burned men, women and children alive simply for being Jews in the Jedwabne pogrom. In the aftermath, some hide their guilt, blaming Nazis for the atrocities they willingly committed. Some Polish politicians are still intent on questioning what exactly happened and who was at fault.

“We revise our wall,” said Golyak. “It’s constantly erased, just like history, and written over.”

Golyak first read Our Class, a controversial play in Poland for its dramatization of Polish-initiated war crimes formerly blamed on the Nazis, about seven years ago. In July, he gathered a cast for a reading and also went to Poland with Stackhouse and Pappelbaum, meeting with playwright Tadeusz Słobodzianek and visiting Jedwabne and Auschwitz. Golyak was most affected by his trip to Lublin, once a hub of Jewish life. When he looked down at the Jewish quarter from a hill, all he saw was a parking lot.

“The biggest impression was the absence,” Golyak said.

Since his 2021 production of The Merchant of Venice, which used exaggerated masks and prop comedy to lampoon centuries of antisemitic tropes, he has been particularly interested in what he called “Jewish displacement stories.”

Too often the real world caught up with his concerns.

On Jan. 15, 2022, when Arlekin was preparing for a performance of Witness, the play about immigrants and antisemitism, a gunman was holding a rabbi and his congregants hostage in their synagogue in Colleyville, Texas. Overhearing an actor rehearse a monologue about how antisemitism follows Jews wherever they go, and monitoring the situation in Colleyville on the TV in the lobby, Golyak decided he would incorporate the footage of the hostage situation into the performance. The live news feed filled the walls of the set.

That night Golyak wrote an op-ed, published on Arlekin’s website, expressing his fear that, after leaving as a refugee from Ukraine 30 years ago to escape antisemitism, “America could be a temporary place of residence for me; I could be forced to leave again.”

This summer, Stackhouse and Golyak shared the story with a group of rabbis in Jerusalem. After they showed clips from the play, an audience member identified himself as Charlie Cytron-Walker, the rabbi from Colleyville.

“Igor’s jaw dropped,” Cytron-Walker wrote in an email, praising Witness as “a creative, engaging way to learn about, feel, and grapple with the antisemitism of our past and present.”

Our Class was months into early production and Arlekin had just opened the play Just Tell No One, about the war in Ukraine, when Hamas terrorists breached the Gaza border and murdered 1,200 people and took some 240 hostage. Members of the company, mostly Jewish refugees, many with connections in Israel, were reeling. In an Oct. 13 article for WBUR, Golyak wrote in support of Israel and expressed his shock at the silence from others in the theater.

“I don’t know if I am an American, or a Ukrainian, or if I am somehow an Israeli, but I know that I am a Jew,” Golyak wrote. “The more we are hated, the more I feel I am a Jew. I feel it every day, no matter where I am, as my people have felt it everywhere throughout history.”

But even though Oct. 7 looms large in the rehearsal room, most pointedly in the play’s scenes of massacres and sexual violence, Golyak doesn’t want it to be the focus. Despite the chalkboard set behind him, he said he’s not trying to teach a lesson from either the Holocaust or the recent past.

“I would rather, with this play, talk about what is going to happen, what will happen, and that seems to me much more urgent,” he said, noting how he is thinking of the world his children will inherit and how to prepare them.

“It’s not about, like, the bad people of the past, some mystical Nazis that did some bad things; it’s to realize that these mystical Nazis can live anywhere and in us as well. And that tragedy is in the mundane. Tragedy can happen anywhere around us,” he paused, “and we just live through it.”

The play Our Class is playing at the Brooklyn Academy of Music from Jan. 12 to Feb. 4. More information and tickets can be found on BAM’s website.