The Jewish playwright who inspired Tom Stoppard to write his Holocaust history

Arthur Schnitzler’s Austria was a major influence on ‘Leopoldstadt’

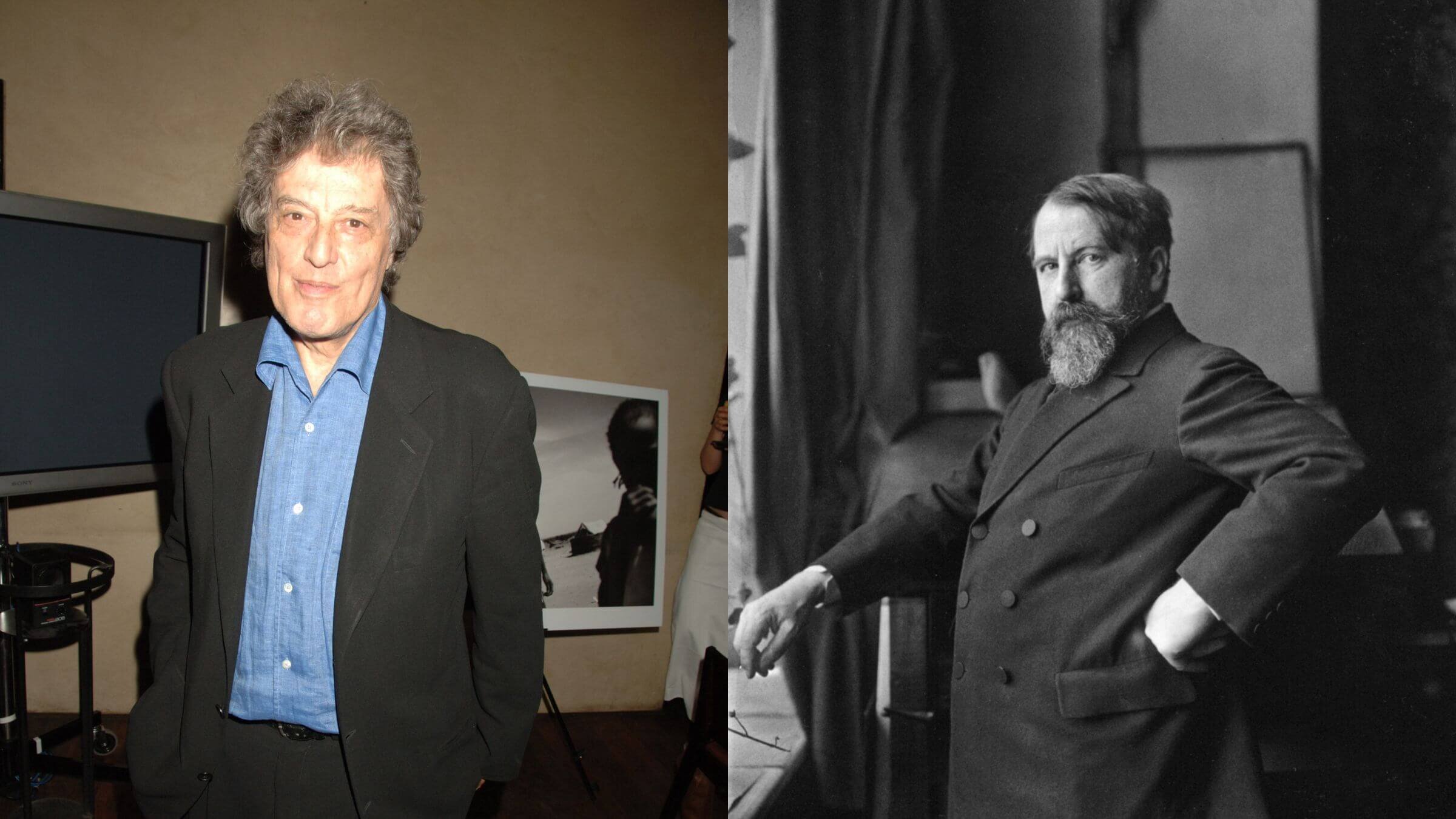

Tom Stoppard adapted two of Arthur Schnitzler’s plays — the older writer’s influence is palpable in Leopoldstadt. Photo by Dave Benett/Getty Images/Ferdinand Schmutzer via Wikimedia Commons

Something unexpected arrives in the middle of Tom Stoppard’s magisterial Holocaust drama Leopoldstadt: a bedroom farce.

Fritz, a cavalry officer, is having an affair with the Catholic wife of Hermann Merz, a Jewish-born textile manufacturer who has recently been baptized and is striving to fully assimilate. During a card game, Fritz makes coarse, antisemitic remarks. Incensed, Hermann goes to Fritz’s quarters to challenge him to a duel, where he finds evidence that uncovers the infidelity: an unpublished play by Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler, inscribed to Hermann’s brother-in-law.

The Schnitzler manuscript is a clue. It’s also an Easter egg. As canny critics, like The New Yorker’s Helen Shaw, observed, this section draws liberally from Dalliance, Stoppard’s 1986 adaptation of Schnitzler’s play Liebelei, down to the callow dragoon named Fritz. And the scenes in this portion of the decades-spanning family saga follow the signature rhythms of Schnitzler’s scandalous boudoir romp Reigen — implied to be the unpublished play Hermann recovers — as one character from a previous scene holds over into another.

“Stoppard uses content and structure to point to a playwright whom many in the audience will not know, and even this unknowing is important,” Shaw wrote. “Stoppard’s subject, after all, is forgetting.”

Among educated, assimilated Viennese Jews — the central characters of Leopoldstadt —Schnitzler was a literary giant known for pieces skewering the bourgeoisie and their penchant for interclass adultery. But by 1900, the year in which Stoppard’s fictional Hermann confronts Fritz, Schnitzler was witnessing a change in Austria, which Stoppard dramatizes. Recently emancipated Jews started to be classed as a separate race, blamed for Communist thought and capitalist greed. A political strain of antisemitism was ascendent. The immigration of Yiddish-speaking, Orthodox Jews from Tsarist Russia rendered even Austrian Jews of long standing suspect.

In his heyday, from around 1900 to 1910, Schnitzler was perhaps the most famous dramatist in the German-speaking world, said Max Haberich, author of a 2021 biography of Schnitzler.

“His plays were popular,” said Haberich. “Each caused a scandal, but it was more because it went against the contemporary mores of the 19th century, and he just wrote about sex a bit too much for the times.”

Schnitzler’s engagement with his Jewishness was central, if by no means constant. Like Hermann, he lived in a society that would never let him forget his origins. He wrote a play, Professor Bernhardi, about a physician undergoing an antisemitic crusade from colleagues in his clinic. (The trendy British director Robert Icke recently adapted it.) That play was banned in Austria, not for anything below the belt, but rather for calling out structural Jew hatred.

One of Schnitzler’s two novels, Der Weg ins Freie, was devoted to the so-called Jewish question, wondering about where this diasporic people belonged in society. Like Leopoldstadt, Haberich said, it presents a broad cross section of Viennese Jewish identity: Its cast includes Zionists and Orthodox observers alongside those who are completely assimilated or even ignorant of their heritage.

But Schnitzler himself was areligious and largely apolitical. He knew Theodor Herzl, and refused to promote one of his Zionist plays. An archival letter attests to his objection that his son attend Hebrew school.

But, Haberich said Schnitzler used matzo as tea biscuits. He had a dim view of those Jews who converted, calling them “renegades.” (He would no doubt regard Stoppard’s Hermann as weak for his opportunistic embrace of Christianity.) He self identified as an Austrian citizen of German nationality and of the Jewish race.

Today, Schnitzler may be best known for providing the source material for Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, which Kubrick, though Jewish himself, largely de-Judaized.

But the little-remembered dramatist also may have inspired Stoppard, late in life, to begin referring to himself as an English playwright of Jewish heritage — and to finally make good on that heritage in what would be his swan song.

Audiences tempted to regard Leopoldstadt as autobiography, about Stoppard’s family’s cataclysmic experience in the Shoah, face a problem: The Merz clan are Austrian and the Sträusslers — Stoppard’s surname at birth — were Czech. Stoppard blithely accounted for the difference in a 2022 New York Times profile by Maureen Dowd.

“It was because I personally didn’t have the background I wanted to write about — bourgeois, cultured, the city of Klimt and Mahler and Freud,” he said. “Where better than Vienna?” And, Dowd wrote, Stoppard had visited Vienna in other plays — his two adaptations of Schnitzler.

Those who faulted Stoppard for his late confrontation with his family history may find Leopoldstadt frustrating. The drama engages with the fate of his relatives, murdered at Auschwitz, but only up to a point. It doesn’t, like his Velvet Revolution play Rock ‘n’ Roll or his translations of Vaclav Havel, explore his Czech side. The material is simply too close. Instead of going outside of his comfort zone, he returned to a place of relative safety: the conventions of Schnitzler.

Stoppard’s 1979 adaptation of Schnitzler’s Das Weite Land was a training ground for Leopoldstadt, boasting a cast of 29 characters, including a naval cadet who cuckolds a lightbulb manufacturer and is shot in a duel.

When Stoppard first took on Schnitzler, he did not yet know the full extent of his background. Yet he boosted not just Schnitzler but also the Jewish Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnár, in 1984’s Rough Crossing. Both writers had largely receded to obscurity; he helped the public to remember them.

Schnitzler died in 1931, before he could meet the fate of the Merzes. But before he did, he had a preview of what was to come in Stoppard’s native Czechoslovakia. On Nov. 3, 1922, during a reading of one of his plays in Teplice, he wrote in his diary the next day that a crowd of “Hakenkreuzler” — “Swastika types” — showed up to cause trouble. A fight broke out when the guards tried to eject them. Schnitzler hid under a table. Antisemitic protesters blocked the entrances, and he had to be escorted to safety.

“That marked him,” said Haberich. “He wrote about that in his diary and said ‘Is this how bad its become?’”