He was a peace activist with a PhD. In dying, Hayim Katsman saved 3 other lives

His grandparents were Holocaust survivors. He was murdered by Hamas on the kibbutz he loved

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

As a dual Israeli-American citizen, Hayim Katsman could have stayed in the U.S. to pursue a career in academia after earning a doctorate from the University of Washington. Instead, he returned to the kibbutz he loved, where he was a gardener, a mechanic and a peace activist.

He was murdered on Kibbutz Holit Saturday by Hamas terrorists.

“I just think it’s chilling,” his mother, Hannah Wacholder Katsman, said in a phone interview from Israel. “My father grew up in Poland. He survived the Holocaust with false papers. My mother was a refugee from Germany who left after Hitler came to power. It’s chilling to me that my son died hiding in a closet.”

His death saved three lives

In dying, Katsman, 32, saved three other lives: His bullet-riddled body shielded a neighbor hiding with him, and that neighbor, Avital Alajem, later saved two children.

His body “absorbed all the bullets,” Alajem told CNN. “I was saved because he was next to the door.”

The terrorists then marched Alajem to Gaza, more than a mile away, taking another family’s 4-month-old baby and 4-year-old boy with them. At some point in the terrifying ordeal, their captors abandoned them. Alajem took the children and managed to make her way back to the kibbutz.

“Hayim in Hebrew is ‘life,’” Alajem said. “That’s the meaning of his name. And he gave life to this planet as he saved me, and I was able to save two kids.”

Alajem visited with Katsman’s mother to tell her the story in person. “One of my friends said, ‘Maybe he inspired her to do what she did,’” Wacholder Katsman said.

‘Stop killing innocent people’

Katsman was involved in various peace initiatives, including Mahsom Watch, which monitors the impact of government activity on Palestinian lives.

Katsman’s sibling, Noy, an activist with Standing Together, which is a grassroots movement of Jews and Palestinians, said Katsman’s death should not be used to justify retribution.

“They always tell us if we’re going to kill enough Palestinians, it’s going to be better for us,” Noy told CNN. “But of course it never brings us peace and never brings us better lives. It just brings more and more terror, and more and more people killed like my brother.”

Noy added: “I don’t want anything to happen to people in Gaza like it happened to my brother — and I’m sure he wouldn’t want that either. That’s my call to my government: Stop killing innocent people. That’s not the way to bring us peace and security.”

Katsman “wouldn’t want innocent people to be killed,” their mother said.

An emerging scholar

Wacholder Katsman is from Cincinnati; her ex-husband, Daniel, is from Seattle. Hayim earned his doctorate in Seattle in 2021 from the University of Washington’s Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies. While there, he lived part of the time with his grandfather.

His research focused on religious Zionist communities, looking at trends, subcultures and the relationship between religion and radicalism. He did fieldwork in Israel, and his dissertation was dedicated to “all life forms that exist between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.”

The Association for Israel Studies called him an “emerging scholar” who had already been published in various academic outlets. He was also the “distinguished winner” of an annual award for best graduate paper.

University of Washington professors noted the cruel irony of his death. “This wonderful human being was killed who had no malice toward either side,” James Wellman told KOMO News.

He had a “very deep concern for all the residents of Israel and the Palestinian territories,” Devin Naar told The Washington Post.

“His work helped illuminate some of the very dynamics that have brought us to this horrific moment,” Liora Halperin told the Post.

Mika Ahuvia, director of the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies, called Hayim “a brilliant bright light in the field of Israel Studies, a citizen of a conflict-ridden region who pursued solidarity and peace, a lover of music, and a great friend.”

Community service

Other tributes mentioned Hayim’s talents as a landscaper, car mechanic, musician and DJ. His volunteering included coordinating an Israel-Palestine research group at the University of Washington, serving as a board member at a center for young adults and teaching Hebrew to teenagers at Kadima, a Reconstructionist congregation in Seattle.

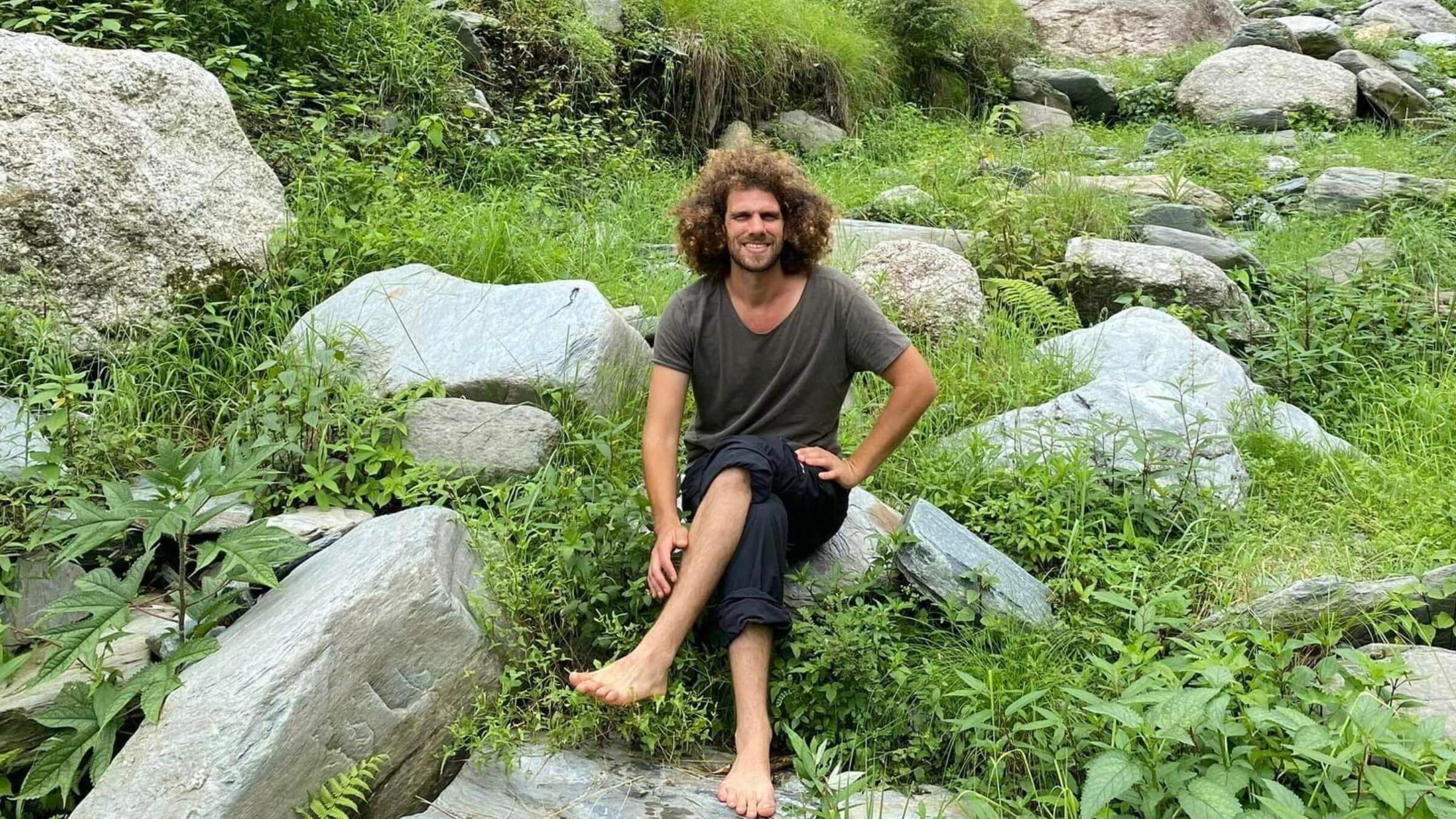

He’d recently traveled to India, a popular destination for young Israelis, and a number of notes posted on his mother’s Facebook page were from travelers he’d met there. “You didn’t have to know him in depth to see his nobility, wisdom, courage, kindness and humility,” wrote one acquaintance.

Katsman was offered a three-year contract to teach in a small American college town, but his mother said “he couldn’t imagine living there.”

Instead, he returned to Kibbutz Holit. He’d originally moved there after completing his army service, helping to “revive this kibbutz that was aging and isolated, and frankly dangerous,” his mother told the Post.

Waiting for the body

Wacholder Katsman said waiting for her son’s body has “been a nightmare. It’s been horrible.”

On Monday night, “they told us they were starting the process,” she said. “On Tuesday, we couldn’t figure out what was going on. We never dreamed we’d get to Thursday morning and we’re still — it could be any minute, it could be next week, we don’t know.”

But she understands that Katsman is one of hundreds of civilians whose bodies are being processed. “They’re not equipped,” she said, “to deal with that scale.”