Pro-Palestinian vandals are painting red inverted triangles on their targets. What does it mean?

Hamas militants have used the symbol. Who else has adopted it?

Palestinian women walk past a graffiti of the Star of David under an inverted “red triangle,” a symbol that Hamas’ military wing, the Qassam Brigades, uses to identify Israeli targets in their videos, in the occupied West Bank city of Hebron on Nov. 30, 2023. Photo by Hazem Bader/AFP via Getty Images

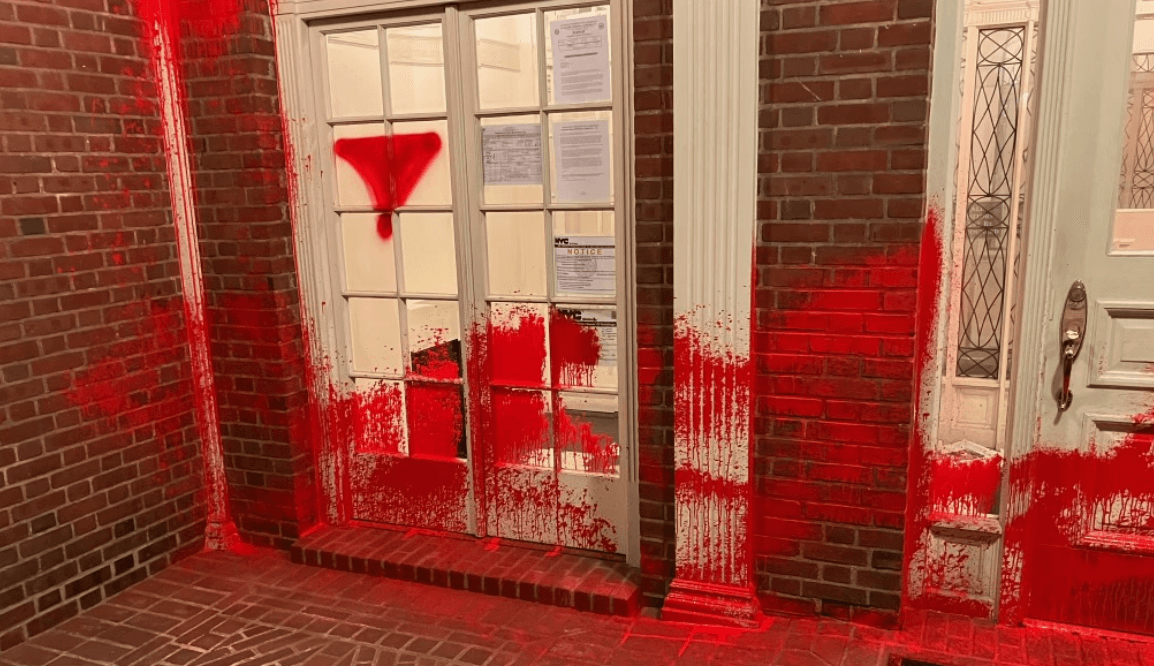

Pro-Palestinian protesters have made liberal use of the inverted red triangle. They daubed it on the apartment building of a Columbia University leader Thursday, on a replica of the Liberty Bell in Washington, D.C., in July and on the home of the Jewish director of the Brooklyn Museum in June. And it’s on signs at protests — on college campuses and in the streets.

In the incident targeting the museum director, New York Mayor Eric Adams and others referred to the triangle as proof of an antisemitic hate crime.

“The mob painted an inverted red triangle on the door — the symbol used by terrorists to mark targets they want to take out,” tweeted a Jewish woman on X, the social platform formerly known as Twitter.

Horrifying vandalism and threats targeting the @brooklynmuseum director and several Jewish board members.

— Aviva Klompas (@AvivaKlompas) June 12, 2024

The mob painted an inverted red triangle on the door - the symbol used by terrorists to mark targets they want to take out.

Threatening and harassing American Jews is not… pic.twitter.com/KojPuPqx9B

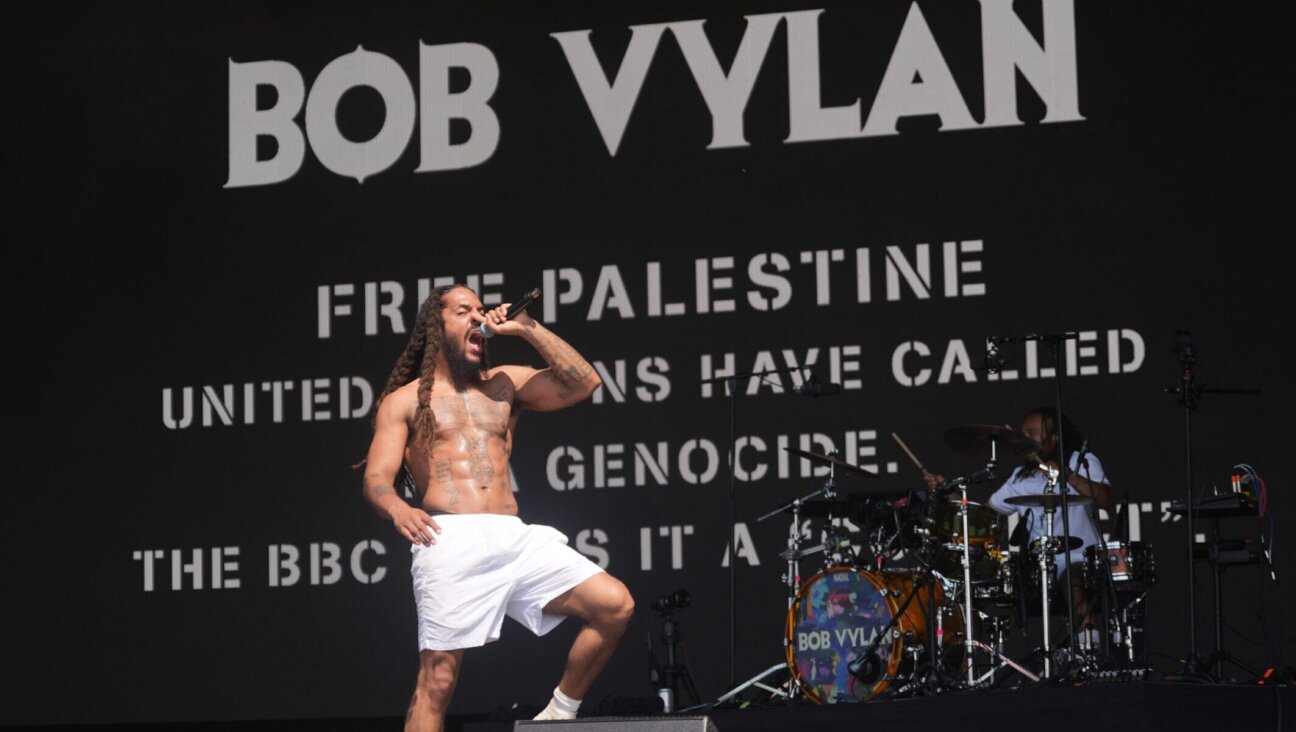

She’s right, in that Hamas and other militant groups in the Middle East have used the symbol to show objects or people — mostly Israeli and Western — they have targeted.

But the symbol has also been used more generally, by those who want to signal support for Palestinian liberation. In that context, said Costanza Musu, a University of Ottawa professor who teaches a course on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the triangle refers to part of the Palestinian flag. As such, she said, it’s used “generally speaking to symbolize resistance.”

She also noted that the Nazis used the symbol to identify people with political views unacceptable to them.

“But it’s a lot harder to say that it wasn’t intended as a way of identifying a target,” she continued, when it’s painted on a Jewish person’s house, far from a college protest where students are using a variety of symbols.

Amy Spitalnick, CEO of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, also knows the upside-down triangle can mean different things to different people. But American Jews have every reason to recoil from it, she said after the museum director’s home was targeted.

“It’s important to understand how it’s being used, how we’ve seen it for years, especially in recent days, including spray painted onto the home of a Jewish person — it’s absolutely wrong, painful, scary, antisemitic.”

When it’s not targeting a specific person or home, Musu said the symbol can be compared to “from the river to the sea,” a slogan heard at many protests against Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. For some it’s a call for the empowerment of Palestinians from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean. For others, it’s a call to eliminate Jews from that land — in other words, the destruction of Israel and even killing of Jews.

“All of this tells us,” Spitalnick said, “that no one is even speaking the same language.”

Police are still investigating the incident at the Brooklyn Museum director’s Brooklyn Heights home, but have made arrests in the case. Homes of three other Brooklyn Museum staff and trustees, though none are Jewish, were also targeted that night.