Jewish Food: A Million Ways To Agree To Disagree

Image by Molly Yeh

If there is one teaching that I remember most from my summer camp Shabbats, it’s that part of being a Jew is challenging your beliefs about God: evaluating and re-evaluating your relationship with God, discussing, and possibly questioning a supreme being’s existence. Whether or not you agree with this idea, it appears that a similar evolving principle can be applied to Jewish cuisine. Simply mentioning the term “Jewish food” often sparks a heated debate and questions arise: Is there such a thing? Where exactly does it come from? What defines it? Is it kosher? Can I eat it with chopsticks?

On Tuesday night at the New School in Manhattan, four food writers and culture academics took part in a panel discussion titled “Jewish Cuisines: The Local and the Global.” Unsurprisingly, a large portion of the time was spent defining “Jewish food,” and even less surprisingly, each had their own unique interpretation.

“Jewish cuisine is almost indefinable and that’s the common ground of all Jewish food,” said June Feiss Hersh, food archivist and author of “Recipes Remembered, a Celebration of Survival.” She pointed out that while many cuisines point to a single country, Jewish cuisine points to “all of the countries that Jews were thrown out of.” Naama Shefi, a specialist in Israeli cuisine, agreed that a similar case is true for Israeli cuisine, bringing to the table quotes from prominent Israeli chefs on what exactly Israeli cuisine is (answers ranged from “indefinable” to simply “salad”).

After establishing that there was no concrete definition of “Jewish food,” the panelists discussed their personal opinions. To Hersh, any food that brings back memories, or that was made by a Jewish grandmother, or that was always at the table on a particular holiday is Jewish food. By her definition, even pizza or Chow Mein could be considered a Jewish food, she conceded.

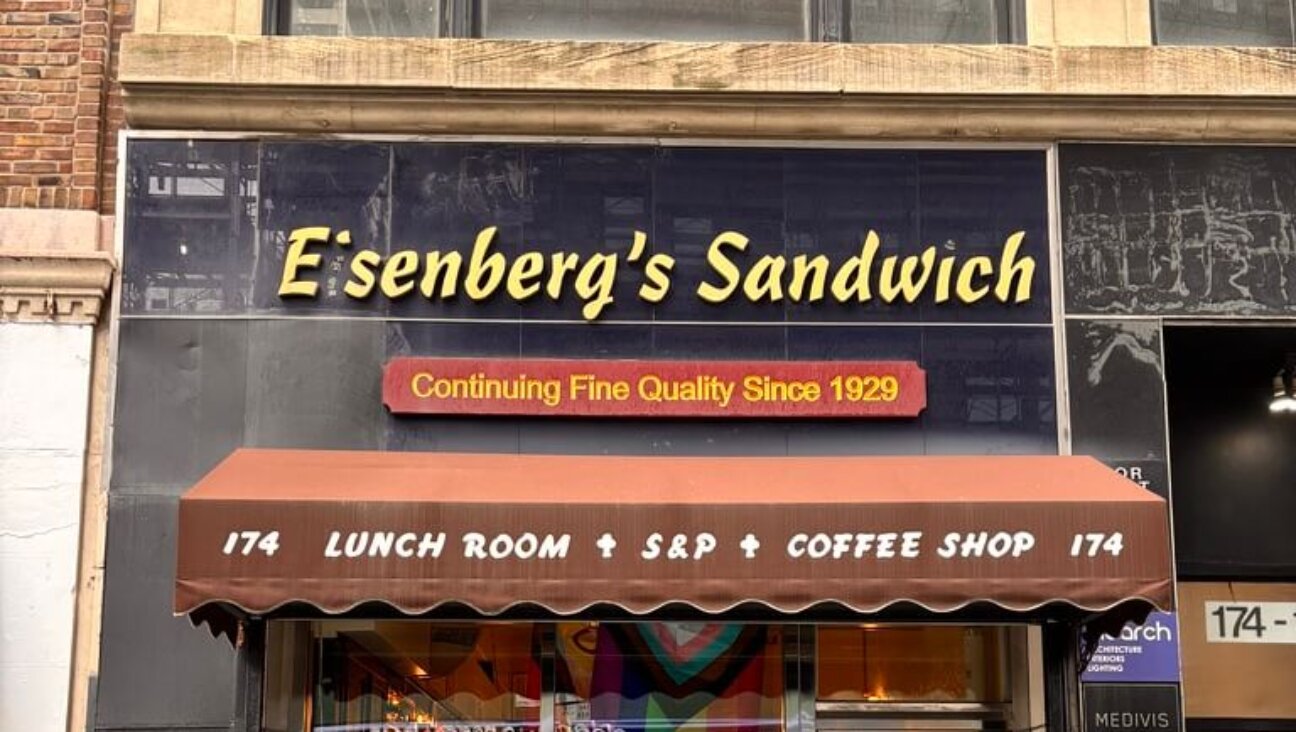

Similarly, Ted Merwin, a professor of religion and Judaic studies at Dickinson College and author of the forthcoming “Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli,” described his a memory of a turkey and roast beef sandwich from a local deli eaten on Sunday nights as his most Jewish food memory. Never mind that turkey isn’t considered Jewish, Merwin argued that the fact that it was a tradition, that it came from a Jewish deli, and that it was eaten with family could have very well made that it Jewish.

Perhaps the definition that surprised me most came from Michele Scicolone, an expert on Italian cuisine and the author of 18 cookbooks. She had the most cut and dry approach. Italian Jewish food, which provided the roots for many popular Italian foods, grew out of anti-Semitic laws in Rome. Forced to live in ghettos and relegated to the discarded parts of animals, dark-fleshed fish like anchovies, and vegetables that the Romans didn’t favor, like artichokes, eggplants, leeks, and celery, Jews developed their own Italian cuisine. Ground meat dishes like meatballs grew out of Roman Jews’ use of discarded meat, and frying foods was a cheap way to stretch a small amount of food — thus the creation of fried anchovies and fried artichokes. Other Roman Jewish specialties, according to Scicolone, include lentil soup, salt cod, tapenade, and lamb. “Needless to say the old ghetto is now very trendy and chic. There’s a resurgence of old restaurants that serve Italian Jewish food,” said Scicolone, who mentioned that Lattanzi, in New York, specializes in Roman Jewish cuisine.

Discussing Jewish food, it seems, involves finding a million ways to agree to disagree. It’s an evolving cuisine that, like the definition, can contradict itself. And just as Jewish cuisine in America is the outcome of being influenced by so many different countries and cultures, it continues to assimilate with American culture. “Pastrami — you can buy it at any Subway or Quizno’s now,” said Merwin, and “for millions of Americans a bagel has no ethnic associations whatsoever.”

With a mention of new trendy Jewish restaurants like Kutsher’s Tribeca, Jack’s Wife Freda, and Mile End, the panelists were quick to agree that this type of cuisine the response of second and third generation Jewish Americans longing for the comfort food that they grew up on. When it Hersh brought up places like Brooklyn’s Traif restaurant and Manhattan’s Joe Dough which serves a Conflicted Jew sandwich (liver and bacon on challah), the audience laughed. But that’s as far as they were willing to humor her. When “Traif can be Jewish” was uttered, heads turned.