My life in delis — an elegy to the Carnegie, the Stage, Charney’s and the Jewish eateries of yesteryear

For one Jewish writer, a delicatessen has been far more than just a place for matzo balls and pickles

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

There’s an old joke about a Jew stranded on a desert island. When rescuers arrive years later, the fellow proudly shows off the two synagogues he’s built. “Two?” they ask him. “You’re alone on a desert island! Why would you need two synagogues?” He points to them and says: “This is the one I go to, and that’s the one I wouldn’t be caught dead in.”

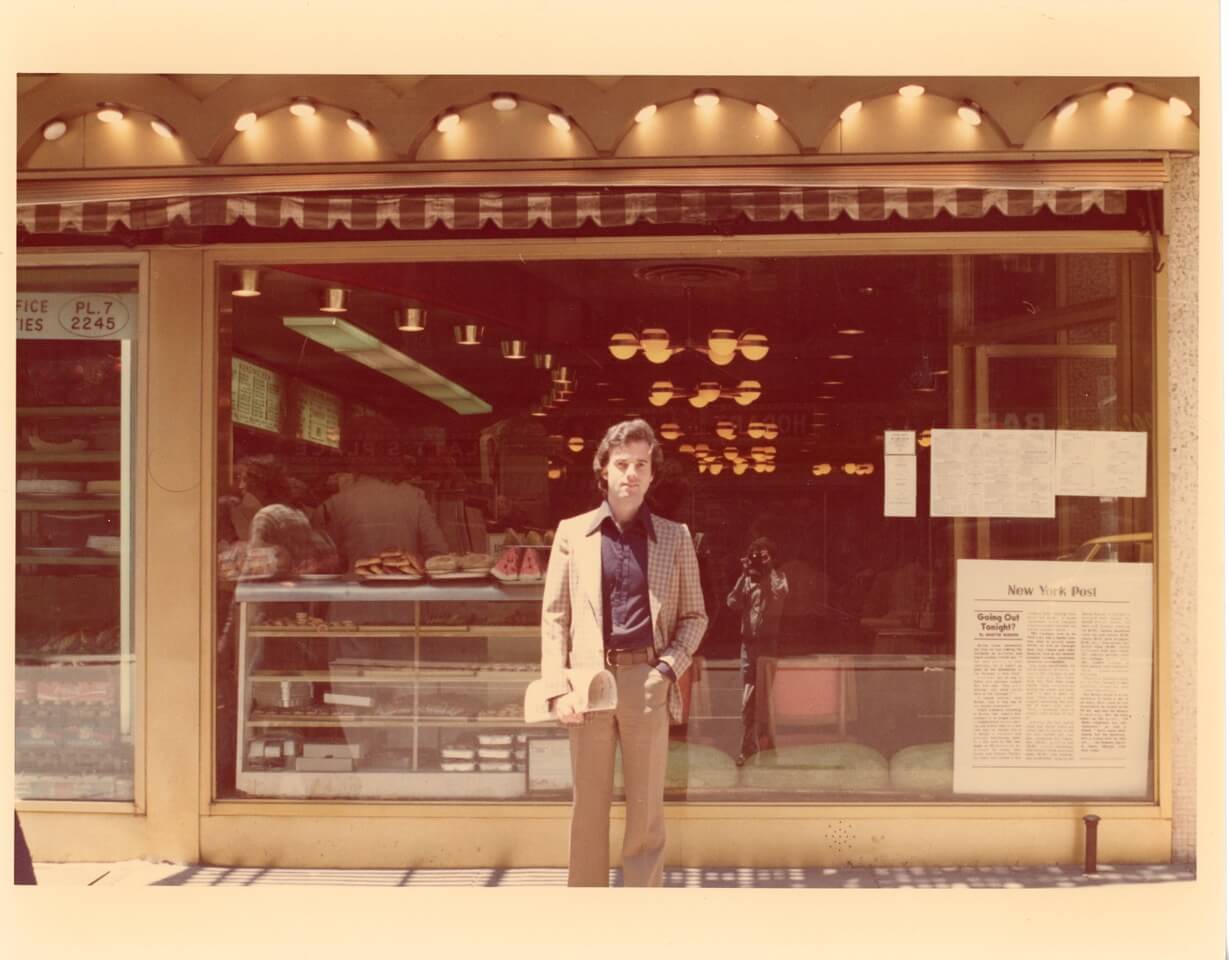

For Jews, it can be the same with delicatessens. In New York, the Carnegie and Stage delis were a block apart on Seventh Avenue. Each had a passionate clientele that praised its virtues and trashed the other place. The Carnegie was the one I went to, and the Stage was the one I wouldn’t be caught dead in. Both establishments are now history — but that’s no reason to stop arguing about them.

My writing partner and I shared an office near the Carnegie in the mid-1970s. The restaurant’s host was a cherubic, sometime-actor named Herb Schlein. In an era before Cheers, he always knew your name.

You could drop in at peak lunch hour and Herb would eagerly snatch up two menus, puff out his chest, and escort you to the one vacant table. To him, it was La Cote Basque and you were Truman Capote. But unlike that genteel eatery, the Carnegie was a cacophony of chatter and clatter and dropped silverware. Diners were so crammed in, if you needed to use the restroom, the next table had to move and let you out or you weren’t going anywhere.

To take your order, a Carnegie waiter would get in your face and say, “Talk to me.” The sandwich I loved then was Tom’s Special. Tom’s consisted of roast beef, chopped liver, chicken fat and Bermuda onion. It needed an FDA warning label. I don’t know who Tom was or why he was thus honored — but to me, the sandwich was more of a Moe than a Tom.

My first deli experience in life was at Lindy’s on Broadway. From the 1920s through the 1950s, Lindy’s was to delis what Radio City was to movie houses. My parents took me there as a kid and pointed out celebrities like Sid Caesar and Rocky Graziano. If you’ve seen the musical Guys and Dolls, when they talk about Mindy’s cheesecake, they’re really talking about Lindy’s cheesecake.

In Jamaica Estates, New York, where we lived in the mid-’50s, we’d have franks and beans at Charney’s, a small neighborhood deli with a handful of booths. I was introduced to sauerkraut there, an acquired taste for a kid. On the deli counter was a paper plate filled with bite-sized chunks of salami, each one stabbed with a toothpick. There was a change dish and a small handwritten sign that said, “A nickel a shtickle.”

I’m not sure why my folks moved us around so much — maybe to expose us to more delis. During my 1955-56 school year in Miami Beach, Wolfie’s and Pumpernik’s were the battling duo. Except it didn’t matter where you ate because they were both owned by the same guy. I remember Wolfie’s as vast and boisterous and exciting, more Lindy’s than Charney’s, with long lines to get in. Mob boss Meyer Lansky was a regular patron. I picture him in a booth with a bowl of cold borscht, facing the door.

In the late ’50s, a bunch of us went to Hebrew school at Rego Park Jewish Center on Queens Boulevard. But first we’d duck into nearby Ben’s Deli and buy a fat dill pickle — dill, not half sour — for 10 cents. Then we’d run into class, still chomping, pickle juice dripping down our shirts. Or sometimes we’d grab a potato knish at Knish Nosh, which sold knishes only, so not actually a deli. More like a culinary version of Just Tires.

At some point, I decided a delicatessen was the perfect spot for a first date. You can relax at a deli and be yourself. A deli says you’re not trying to impress. There’s nothing fancy about it, and your pastrami on rye won’t come deconstructed. If the girl agrees to a second date, it’s not because she wants more of this kind of glam. It’s that she wants to see you again.

My first date with my first wife was at Canter’s delicatessen in LA’s Fairfax District. As befits a Hollywood deli, Canter’s has a marquee and lots of neon and a big sign that says, “Open All Night.” It’s a sprawling place with a deli counter and a bakery and a performance space called the Kibitz Room. My sister, Susan, who took up comedy at age 60, once headlined there.

However, it didn’t bode well for a marriage that Canter’s and I had a history.

In 1966, I drove cross-country with two pals to spend the summer in LA. Canter’s, then, had become a hip after-hours spot, a kind of Rick’s Café Americain with matzo ball soup. Its habitués included a 20-something Phil Spector, tablehopping in an Irish driving cap, and a Viking-helmeted blind musician named Moondog. Crowds of so-called hippies and flower children overflowed the sidewalk, and the “fuzz” were determined to clear them out. On a warm July night, three of us, and our three dates, paid the check, stepped out the door, and were swept up in a police raid.

According to an article in the Los Angeles Free Press from July 15, 1966, “The ‘Canter’s bust’ included ‘longhaired undercover agents wearing LSD and anti-police buttons, plainclothesmen piling out of a pick-up camper, men in blue, flashing red lights, police photographers and double-parked squad cars, huge LAPD transport buses with barred windows and a ‘Black Maria.’”

276 people were arrested for “blocking the sidewalk” and carted away. There was no such crackdown on LA’s rapists and murderers. But in what may be the best deli service ever recorded, Molly, our Canter’s waitress, saw us get pinched, followed the prisoner buses downtown, and posted our $330 bail. How much do you tip for that?

During the years I wrote for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show, I’d stop each morning at Art’s Deli (“Every Sandwich is a Work of Art”) in Studio City on my way to Burbank. Over coffee, bagel and half a grapefruit, I’d scan the papers for news items to use in Johnny’s monologue. There were two competing delis then (it’s always two) on that stretch of Ventura Boulevard. Art’s was the one I went to, and Jerry’s was the one, well, that I rarely went to. Today, Art himself is gone — but his gargantuan sandwiches live on.

In fall 1991, I stopped into Nate ’n’ Al’s deli in Beverly Hills to buy sliced turkey and challah for my kids’ lunches. A woman I’d met once at a children’s party was also paying her check. “We should get our boys together,” she said. “And by the way, my husband left me for another woman, if you know of anyone to fix me up with.”

“I’m going through a divorce myself,” I said.

Our first lunch date was at Broadway Deli on the Third Street Promenade. I don’t remember what we ate, but I remember what she wore: blue jeans overalls, a green cape, and red vinyl clogs. She said, “You might as well know who I am now.” Well, Fredde and I are still together, but the deli closed in 2010.

My father’s health was precarious when he moved to LA to be near us in 2004. I’d often rescue him from assisted living and take him to lunch — more than once at Factor’s, the haimish deli on Pico, south of Beverly Hills. We were at a corner table one day, schmoozing over lox, eggs and onions, when the owner, Marvin, happened by. I knew him slightly, as our daughters were school friends, and introduced him to Milt. As he went to take his leave, Marvin leaned down and quietly said to me, “Savor it.” He wasn’t talking about the food.

I savored, too, my lunches with Max. As in the film My Dinner with Andre, my son and I had a long-running conversation about life at Izzy’s deli on 15th and Wilshire. It was a chat that ran for years. We hated the hassle of choices, so it was almost always Izzy’s and almost always scrambled eggs, potatoes, toasted bagel and a large orange juice. Max suffered from depression and crippling anxiety, and a typical lunch would find me trying to alter his trajectory.

We talked about the past, how our family had overcome antisemitism, pogroms, and the Depression. We talked hopefully about a future, too. And, ineptly, I would lob notions at him: Walking is great for your mood … A lot of people swear by meditation … Let’s get you a trainer … A daily workout at the Y would be great … You need to hang out more with your friends … Here’s a book you might find helpful … Maybe you’re taking too many meds … Are you taking the right meds? … Should we change therapists? And so on.

In the best of times, he walked a tightrope. Three months into the isolation of the pandemic, he fell off it. Just shy of his 38th birthday.

It seemed fitting that Izzy’s, closed for the pandemic, never reopened.

Despite closings, the Jewish delicatessen has shown signs of life. Warhorses like Barney Greengrass in New York and Langer’s in LA are thriving. And delis with new business models have sprung up — like Russ & Daughters Café on the Lower East Side, with its martinis and caviar; and the stripped-down, no-nonsense Wexler’s in Santa Monica. But if you want your grandkids to know the thrill of taking a number at the counter and waiting and waiting, it’s up to you. So, support your local deli. Would it kill you to order a smoked fish platter?