The challah that changed everything: Tracing Jewish baking back to Poland

Laurel Kratochvila’s Dobre, Dobre brings Jewish baking home

Laurel Kratochvila, author of Dobre Dobre, in front of her bakery, Fine’s Bagels, in Berlin. Courtesy of Chronicle Books

Laurel Kratochvila was a 23 year-old from Sharon, Mass. living in Prague, working as a bartender, when she crossed into Poland with her boyfriend, entered a village bakery, and bit into a loaf of braided bread that the baker called chalka.

Then her life changed.

“I ripped into the still-warm loaf and stuffed long strands of fragrant egg bread into my mouth,” she writes in her new cookbook, Dobre Dobre: Baking from Poland and Beyond. “How was it that we’d traveled little more than an hour and suddenly, in this little bakery in this little Polish town, I felt more at home than I had in a year?”

That chalka — a variety of challah made with milk — led Kratochvila, beginning in 2009, on a years-long journey to uncover a hidden truth: the Jewish baking traditions that Americans know and love — bagels, rugelach, babka, kichel — didn’t just happen to resemble Polish baking. They are Polish baking, created by the Jewish bakers who once dominated the trade in pre-war Poland.

Her beautifully-illustrated 329-recipe cookbook reads at least partially as an archaeological expedition, as she excavates how deeply Jewish bakers shaped Polish cuisine — and how their legacy survived even after most of the bakers themselves did not.

After her challah epiphany, Kratochvila moved to Berlin, learned baking, opened the popular Fine Bagels bakery, and, in 2022, wrote the James Beard Award-nominated New European Baking, partly, as she wrote, to “comfort bake Yiddish classics.”

“It was absolutely homesickness baking,”she told me when we spoke by Zoom while she was on a bagel baking break in Crete.

She couldn’t find the Ashkenazi baked goods of home where she had settled in Berlin, but during her research in Poland, she found them everywhere — even if their Jewish roots had been forgotten.

“I had been somewhere so unfamiliar for so long, and then suddenly, yes, this is the taste, this is the smell,” she told me. “For the first time being in Europe, there was something that I felt belonged to me.”

The erasure and the evidence

What nagged at Kratochvila wasn’t just her own homesickness, it was how others ignored what to her she could literally smell and taste. She noticed that a best-selling cookbook on European baking — she didn’t want to name names — didn’t mention Jews at all, save for one caption below a photo of a hamentaschen. It read, “Jewish cookie.”

“There was a kind of cultural erasure,” she said. “I wanted to tell the broader story of where these recipes came from, and where they went.”

The numbers tell that story.

Before World War II, an estimated 50% of Poland’s bakers were Jews, despite comprising just 10% of the population.

Baking was historically one of the few professions allowed to Jews, and they thrived and innovated.

Jewish bakers fashioned both chalka, the often braided bread made from a sweetened milk dough, alongside its milk-less counterpart, challah.

Working in the rented corners of basement bakeries, they baked bagels, a job so lowly it gave rise to a Yiddish curse Kratochvila translated for me, “Go lie on the ground and make bagels.”

They made kichel, the light as a feather bow-tie shaped cookies, in both sweet and pepper varieties. They baked szarlotke, custardy apple cakes beloved in every Polish home. And of course bialys, the flattened, onion-topped rolls.

“The bialy was the signature Jewish baked good of Bialystok,” Kratochvila said, “which is why it’s not made there anymore.”

Lost in translation

After the war reduced Poland’s Jewish population from 3.3 million to 300,000, many recipes vanished with their murdered creators. The knowledge that survived did so in the Jewish bakeries that bloomed in American cities like Boston, where young Kratochvila first inhaled the scents that would later spin her life around in a Polish village.

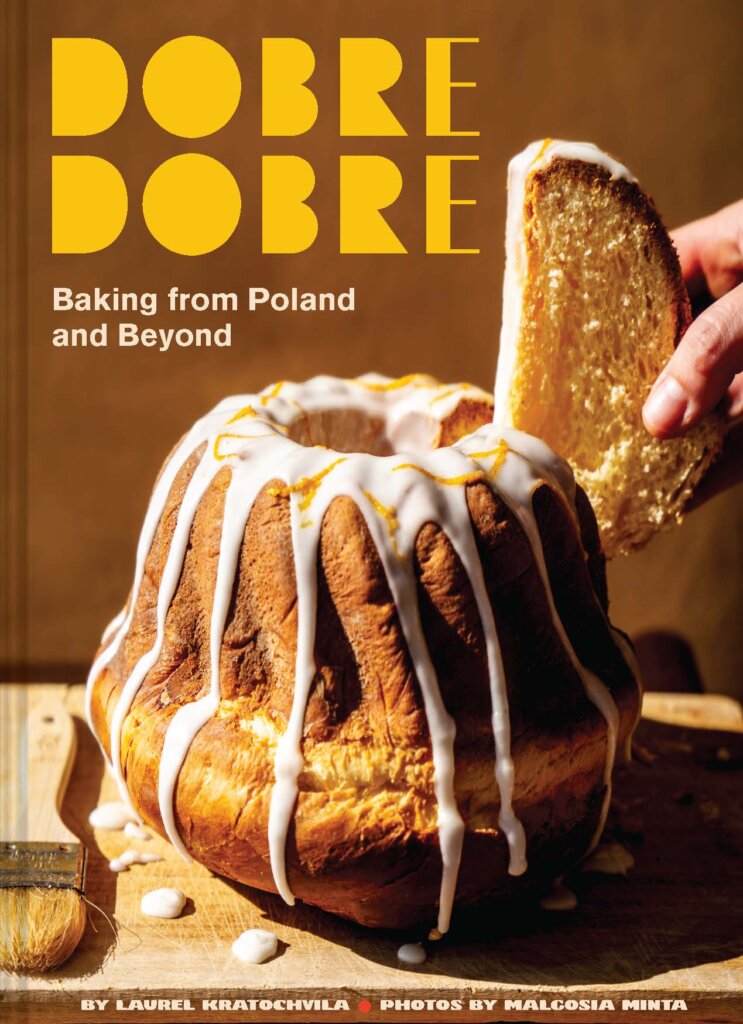

Dobre Dobre uncovers how the “Jewish” bakery goods Americans know today transformed in their journey across the Atlantic. Rugalach spread worldwide. In America, they became stuffed with chocolate chips. In Israel they are drenched in a sticky syrup. Those Instagram-famous Jewish-style babkas? They’re actually closer to filled yeast breads called strucle. In Poland, babka refers to a Bundt cake familiar to anyone who’s attended an Ashkenazi shiva.

The peppered version of kichel didn’t survive the journey — a shame — but so many other breads, cookies and cakes did. That’s why, as I told Kratochvila, when I walked past a bakery in Warsaw, the scent instantly transported me to Bea’s Bakery, my own childhood in the San Fernando Valley, thousands of miles away.

“That’s why you can’t approach Polish baking without bringing in the Jewish part,” Kratochvila said. “In that way, this is a very Jewish book, without being a Jewish book.”

The revenge of the $6 bagel

Dobre Dobre — the phrase roughly translates as “sweet, but not too sweet” in Polish — contains many recipes that don’t appear at Bea’s or Zabars: sour cherry and sweet cheese pastries, a towering cream-filled meringue studded with red berries, and donuts oozing plum butter, which look like the ultimate sufganyot.

The Jewish recipes revive a kind of Old World richness. Last Friday I made the recipe for challah, which calls for five egg yolks, sugar, oil and vanilla, producing a bread that was pillow-soft and gently sweet—the bubbe of all challahs.

In Poland today, Katochvila said, non-Jewish bakers are reviving bagels, bialys and other Jewish staples, not always aware that they aren’t innovating, but restoring.

And those almost-lost recipes are coming back on both sides of the Atlantic as bespoke, artisanal and pricey. I told Kratochvila that people stand in line for two hours to pay $4 for a single handmade bagel in L.A.

“I have to open my bagel shop in L.A.,” she said. “I’m only charging two bucks.”

The experience of walking into those bakeries and walking out with recipes that were part of her own culture, “scratches a particular itch of belonging,” she said.

“That’s why you or I could go to Poland today, and walk into a bakery, and feel familiarity and recognition,” she said.

In that recognition lies something profound, the power of food to call us back home, no matter how far we are from it, or from ourselves.