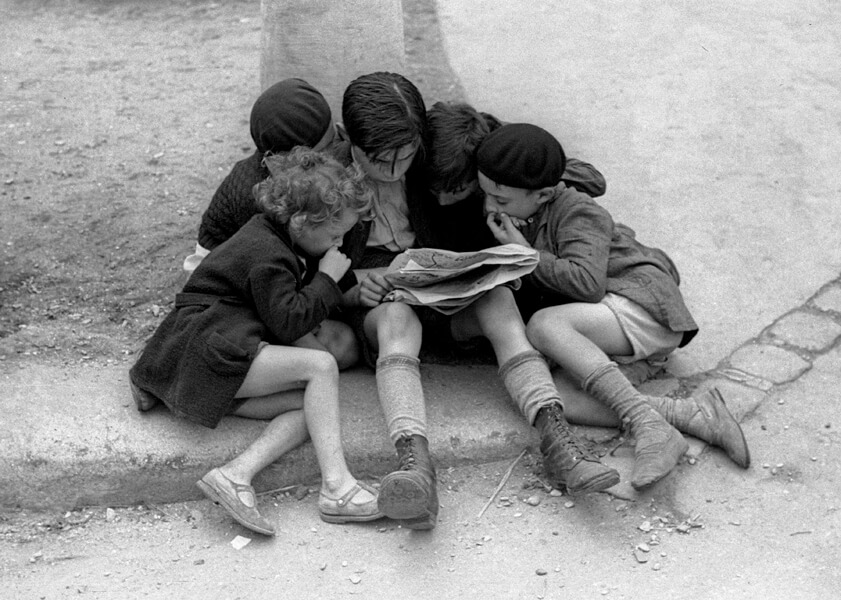

He captured striking images of city life. Why haven’t we heard of him?

Fred Stein also created portraits of many luminaries, including Albert Einstein. Now his son and others are introducing Stein’s oeuvre to a new generation

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

If the first casualty of war is truth, the second may well be works of art.

This was likely the case for photographer Fred Stein, a Dresden-born Jew whose fame may have been hampered by the Holocaust and immigration — first to France, then to the United States. Stein, who took some of the most iconic photographs of mid-century artists, intellectuals and political figures, is the celebrated photographer whose name you probably don’t know.

At least three people have made it their mission to restore Stein’s place alongside the 20th century’s great portraitists and street photographers. One is Marianne Rosenberg, champion of Stein’s work in a gallery otherwise devoted to painting.

“Fred Stein’s photographs represent a bygone time and place, and are artistically strong in terms of subject and composition,” Rosenberg said. “They really are special works.”

Another advocate is Rachel Stern, founder of the Fritz Ascher Society for Persecuted, Ostracized and Banned Art. On the organization’s website, you can watch “Out of Exile,” a documentary that showcases Stein as a leading innovator of hand-held photography.

“It was Hitler’s aim to crush artists such as Fred Stein, and ensure their art was never seen again,” Stern said. “Stein’s artistic and political importance helps us ponder the pressures on artists, and on all of us, inside a totalitarian system.”

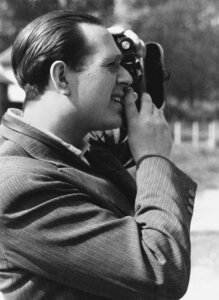

The third, and most poignant, proponent of Fred Stein’s photography is his son, Peter Stein, a cinematographer (Reuben, Reuben; Pet Sematary) whose own passion, at age 79, is to bring his father’s work to the world’s great museums and introduce a wider audience to it. In fact, it was Peter Stein who directed the documentary Out of Exile and co-wrote it with his wife, film editor Dawn Freer. Irene Höfer produced it.

When Fred Stein died in 1967, his son was 23, married and teaching fourth grade in the South Bronx. Peter’s voice has a tinge of sorrow when he describes the conflict that kept father and son from sharing their love of the visual arts with each other.

“When I was too young to go outside by myself, I was totally immersed in my family,” Peter said. “My father and I would go to museums together. He’d point out where the light comes from in a painting, or note the tree arching over from the left and framing the image.

“As I got older, though, my father was out taking photographs and my mother was out working. I was left alone with my older sister, but mostly I was out on the streets of Washington Heights. We kids were avid baseball fans. Yet my father couldn’t have cared less about baseball. His reality was completely different from mine, and we experienced a big generation gap between us.”

‘How did my son turn out like this?’

Even as a child, though, Peter understood that his father was revered, inside and outside the family. “He was a real intellectual,” Peter says. “He had trained as a lawyer in Germany, but as a Jew, he couldn’t do the requisite internship. My father read Time, Newsweek and The New York Times, and several books a week. As a socialist, he had strong opinions, but he could talk with anybody on any level.”

Peter is rueful when he considers that his father may have loved talking to people even more than photographing them. Perhaps he was more comfortable with them than with his own son?

“I used to believe my father thought: ‘How did my son turn out like this? He’s not at all who I would’ve hoped for,’” Peter mused.

With Peter now 20 years older than his father lived to be, he’s on an urgent mission to express his gratitude.

“I didn’t appreciate just how much I learned from my father,” he said. “Composition. An appreciation for good lighting. Good taste. I used to tell my students at the NYU Tisch School of the Arts, where I taught cinematography, that I learned these skills from my father.”

As a cinematographer, Peter met actors, presidents, scientists and writers — just as his father had. He thought, “Why not try my hand at my father’s craft?” He bought a small camera and photographed Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Jimmy Stewart, Aaron Copeland and many other towering personalities.

“But my portraits were boring,” Peter conceded. “For one, I was behind a movie camera and couldn’t engage people in conversation the way Fred had done. His pictures of famous people were interesting and meaningful. Mine were ordinary snapshots. What my father could do wasn’t something just anybody could do, not even a cinematographer.”

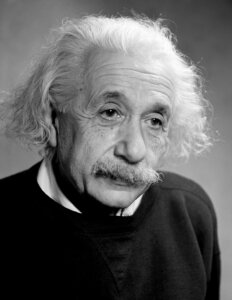

By way of example, Fred Stein took a photograph of Einstein that remains the world’s most characteristic shot of him.

“Fred and Einstein were together for two hours,” Peter recalled. “He took 24 pictures of him. Twenty-four pictures of Einstein! A photographer today with a modern camera would knock off 2,000 photos and choose the best 10. It kills me when I look at my father’s photos. They’re all really good.” (Peter talks about Einstein’s portrait on YouTube.)

A search for filial redemption

Peter acknowledges a redemptive motive in his drive to resurface Fred Stein’s photography. When he stopped working as a cinematographer and professor, he committed himself to thanking his father for teaching him how to see. He began by building on the Fred Stein archive, the project his mother started as a way of organizing the 1,200 enduring portraits Stein took throughout his adult life. These included intellectuals, politicians, artists and scientists, such as Hannah Arendt, Richard Wright, Thornton Wilder and Fidel Castro.

The archive also showcases Stein’s pioneering street photography set in 1930s Paris and New York in the 1940s and 1950s.

“Even if I weren’t his son, his work is so exceptional, I’d feel a responsibility to preserve his photography for the historical record,” Peter said.

Between intention and execution lay many formidable obstacles.

“I thought all I had to do was go to a few galleries and museums, and they’d see how great my father’s work is, and the attention would flow naturally from there,” Peter said.

Easier said than done.

From the 1930s to the1960s, Fred printed his portraits and street scenes himself. Although these one-of-a-kind vintage prints should be valuable today, artistically and commercially, Peter understood that most people won’t buy works from an unknown photographer. He decided to approach small galleries, which might focus on the inherent artistry of the photographs.

Sole photographer among Picassos and Van Goghs

Peter’s greatest coup was the Rosenberg Gallery on 66th Street in Manhattan, run by Marianne Rosenberg. The Rosenberg pedigree begins with Alexandre Rosenberg (1842-1913), the French art dealer who represented the work of Paul Cézanne, Edouard Manet, Vincent van Gogh, and other Impressionists, and continues with Paul and Léonce Rosenberg, the exclusive dealers for Picasso, Matisse and other artists. Marianne’s father Alexandre P. Rosenberg continued the family business — despite the Nazi theft of hundreds of paintings. (Some 400 works have been returned to the Rosenberg family). To date, Stein is the only photographer featured in the gallery.

By now Peter focuses exclusively on getting museum shows. Gallery sales help support his travel expenses to countries with outstanding museum collections. He has stopped showing reprints in smaller spaces because, he believes, Fred’s work, especially the rare original prints, belongs in the world’s great museums.

“It’s really hard to get appointments with curators and museum directors,” Peter said. “I get the feeling people think: ‘If your father was so great, how come I never heard of him?’”

Peter Stein’s efforts may be reaching critical mass with the support of Rachel Stern’s Fritz Ascher Society.

“Rachel contacted me to say she saw Fred’s work at the Rosenberg Gallery,” Peter said. “She wanted to know everything about my father.”

He told her about Out of Exile, which has already won awards at film festivals in Paris, Prague and the U.S. In 2021, it won first prize from the Spotlight Documentary Film Awards.

Out of exile — and back to Germany

Peter hopes Out of Exile will bring Fred Stein out of obscurity. Perhaps the father would have appreciated the irony of history that has sent the son back to Germany many times to accomplish the task.

“To my surprise and delight, I have met such wonderful people in Germany,” Peter said. “We were able to raise money for our film from the Lower Saxony Film Commission. As for museum showings, I’ve had better luck in Germany than in the U.S.”

Peter concedes that his mother never wanted to set foot in Germany again. “Yet my father never stopped loving his native country,” he said. “After my mother passed away, I came upon a book of essays my father was compiling. He titled it This Was Not Our Germany. His bond with pre-Hitler Germany held fast.”

Peter again contemplates the divide that kept father and son at arm’s length. “I didn’t even know he was working on a book,” he said. “But I’m bridging the divide between us now. Reintroducing Fred Stein to the world and bringing his oeuvre to light is my full-time job. His career is now my career. Nothing is more rewarding to me than that.”

Out of Exile, a documentary by Peter Stein and Dawn Freer, is viewable on the Fritz Ascher Society website until Dec. 31, 2022.