Why music scholar Henry Sapoznik returned a painting he won at a raffle

‘The Wedding’ is one of hundreds of paintings that self-taught Jewish artist Mayer Kirshenblatt did of his hometown, Opatow

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

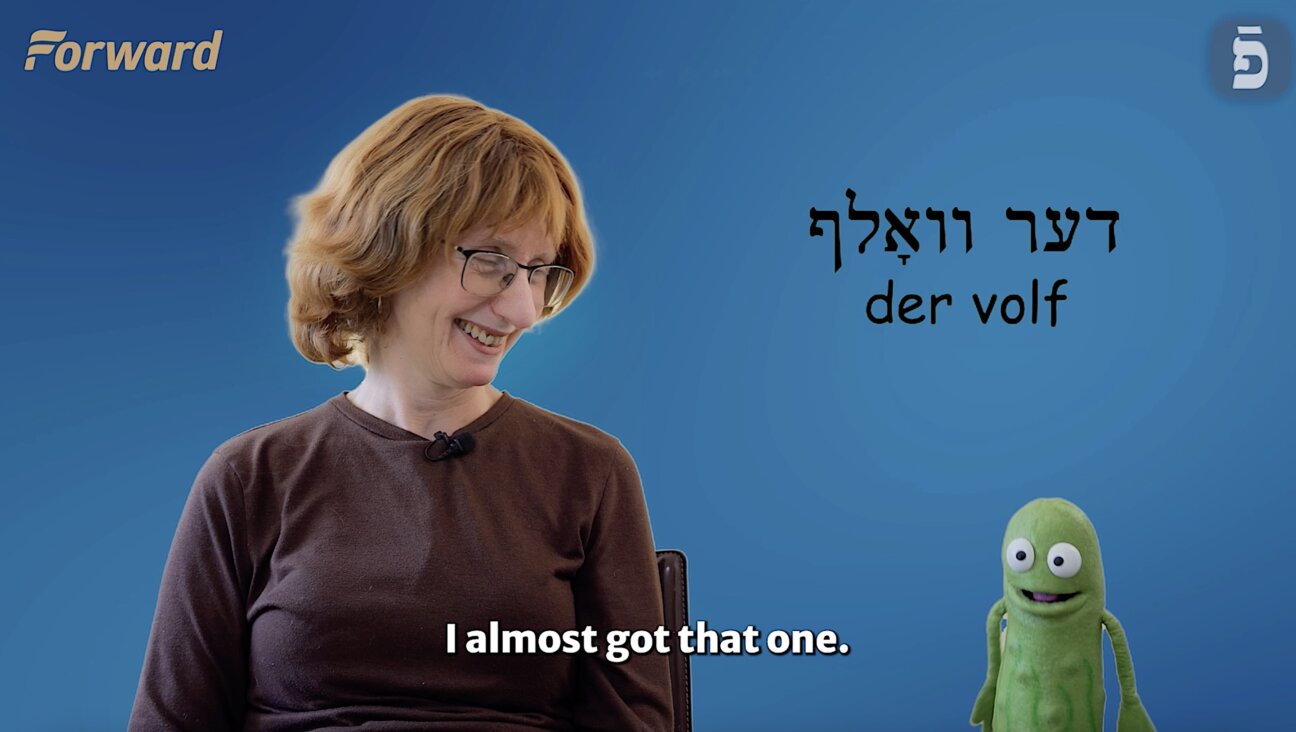

Sometimes the story of a single work of art — in this case a painting by the extraordinary self-taught Jewish artist Mayer Kirshenblatt (1916-2009) — is much more than the sum of its parts.

The painting, The Wedding (1992), reflects a long and meaningful friendship between the klezmer music performer and scholar Henry Sapoznik and the folklorist and museums expert (and Mayer Kirshenblatt’s daughter), Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett — both important figures in the world of Yiddish culture. It depicts a traditional chuppah ceremony, complete with joyful guests and a klezmer band, in the Polish shtetl where Kirshenblatt was born and raised before World War II — Apt (known in Polish as Opatów).

By the time Kirshenblatt depicted this scene, he had lived in Canada for many decades, but his memories of his childhood town, which he recorded in over 300 paintings and drawings, remained vivid. The Wedding embodies key aspects of Kirshenblatt’s life and art, including the importance of memory and the possibility of self-renewal regardless of age. The latest chapter in the painting’s history also demonstrates the power of friendship, and projects a hopeful future for appreciation of Jewish culture in Poland, which Kirshenblatt left in 1934.

The shtetl, Apt, was a colorful place

Mayer Kirshenblatt was born in Apt at the height of World War I. He attended both cheder and Polish public school, but as Kirshenblatt-Gimblett points out, “his real school was the town.” He was an observant child with an exceptional visual memory, fascinated by every aspect of Apt’s bustling Jewish and non-Jewish life: the home, the synagogue, the street, the workshop and the marketplace. It wasn’t until much later that he started creating his art, but his child’s mind stored up a treasure trove of visual materials.

Young Mayer was an outsized personality in his own right. His fellow Apters gave him the nickname “Tamez,” meaning “July.” In his own words: “July was the hottest month of the year. Mayer Tamez means Crazy Meyer. People get excited when it is hot, and I was an excitable kid.” He was attuned to human dramas big and small, and could later recall people and incidents in astonishing detail. Not only did he become a painter; he turned into a wonderful raconteur, telling his daughter Barbara stories about life in his hometown that ranged from the comic to the dramatic to the downright odd.

Apt was a colorful place, both literally and figuratively, and the impressions it made on an unusual boy resulted in a unique book combining paintings with stories. The book, They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland Before the Holocaust, was co-authored by father and daughter. No similar record exists for any other pre-Holocaust Jewish community in Europe.

Recalling visual details from his childhood

But becoming an artist was not natural or easy for Mayer. He was 17 when he left Poland for Toronto in 1934. (His father had already gone to Canada six years earlier). After stints sewing in a sweatshop and painting houses, Mayer opened a wallpaper and paint store. In the 1960s, as Barbara Kirshenblatt’s professional interest in Jewish folklore developed, she began to sense that her own father was a rich repository of knowledge about Jewish life in Europe and recorded a series of interviews with him.

As he told his stories, his family realized that he had a remarkable capacity to recall visual details from his childhood. His wife, Dora, as well as Barbara and Barbara’s husband, Max, urged him over many years to draw and paint what he remembered. He resisted, doubting his own abilities as an artist.

But finally, in 1989 — at age 73 — he created his first drawing, then his first painting. The floodgates opened quickly. Fortunately Mayer lived to be 93, so he was able to make art for 20 years. At first glance, his style seems naive but it’s actually very sophisticated, with a strong sense of narrative and careful use of vibrant colors to structure each scene. The life these paintings (re)create is both deeply subjective and entirely believable: They are valuable not just as a record of a lost world, but also as one man’s experience of that world — lived as a child and recalled through an adult lens.

Sapoznik wins ‘The Wedding’ in a raffle

It’s no wonder that Mayer’s paintings were featured in solo exhibitions at prestigious museums including the Jewish Museum in New York, the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam and the Judah L. Magnes Museum — today the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life — at the University of California, Berkeley.

When Mayer returned to Apt in 2007, he was treated as a celebrity: The town put up posters announcing his lecture at the local museum and even gave him a standing ovation. In 2008, Apt hosted an exhibition of his paintings complete with a ribbon-cutting ceremony by county officials. And in 2024, his artwork will be on display in the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw.

The Wedding was created in 1992, only a few years after Kirshenblatt began painting. It was made specifically to be raffled off at KlezKamp, an annual Yiddish music and culture festival founded by Sapoznik in 1985 which ran for 30 years. (Today’s festivals Yiddish New York and KlezKanada are actually “descendants” of KlezKamp.) The Kirshenblatt family, including Mayer, were enthusiastic KlezKamp participants from its earliest days. The Wedding prominently features klezmer musicians, and was the perfect item to sell for KlezKamp’s benefit.

To his astonishment, Sapoznik won the raffle. His connection to all the Kirshenblatts was deep and warm, but his friendship with Barbara was particularly key: She had been one of the first and strongest supporters for ventures such as his groundbreaking Smithsonian Folkways recording of historic klezmer performances in New York City.

Upcoming exhibit of Mayer Kirshenblatt’s paintings

Over time, Henry and Barbara remained close. Both became major scholars in their fields. Sapoznik, who recently received a lifetime achievement award from the Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC), has two forthcoming books: A Tourist’s Guide to Lost Yiddish New York and Hear, O Israel: A Century of Yiddish-American Broadcasting.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett is the Ronald S. Lauder chief curator of the Core Exhibition at the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. She carefully kept her father’s collection of paintings intact over the years, and convinced her family to give all of them to the POLIN Museum. When she recently asked Sapoznik for a photograph of the painting in his possession, in order to complete the list of Mayer’s works, Henry offered to return the painting to her for the POLIN Museum.

POLIN Museum visitors have numbered in the multiple millions since the museum’s grand opening in 2014. Seeing Mayer’s paintings in the show planned for next year, Post-JEWISH: Shtetl Opatów through the Eyes of Mayer Kirshenblatt, will fulfill Mayer’s own stated goal: to help future visitors understand how Jews in Poland lived, and not only how they died.