An exciting, new way of thinking about refugee modernist artists like Yonia Fain

The exhibit “Modern-Ish” shows us how to categorize Eastern European Jewish artists who were forced to flee their homelands

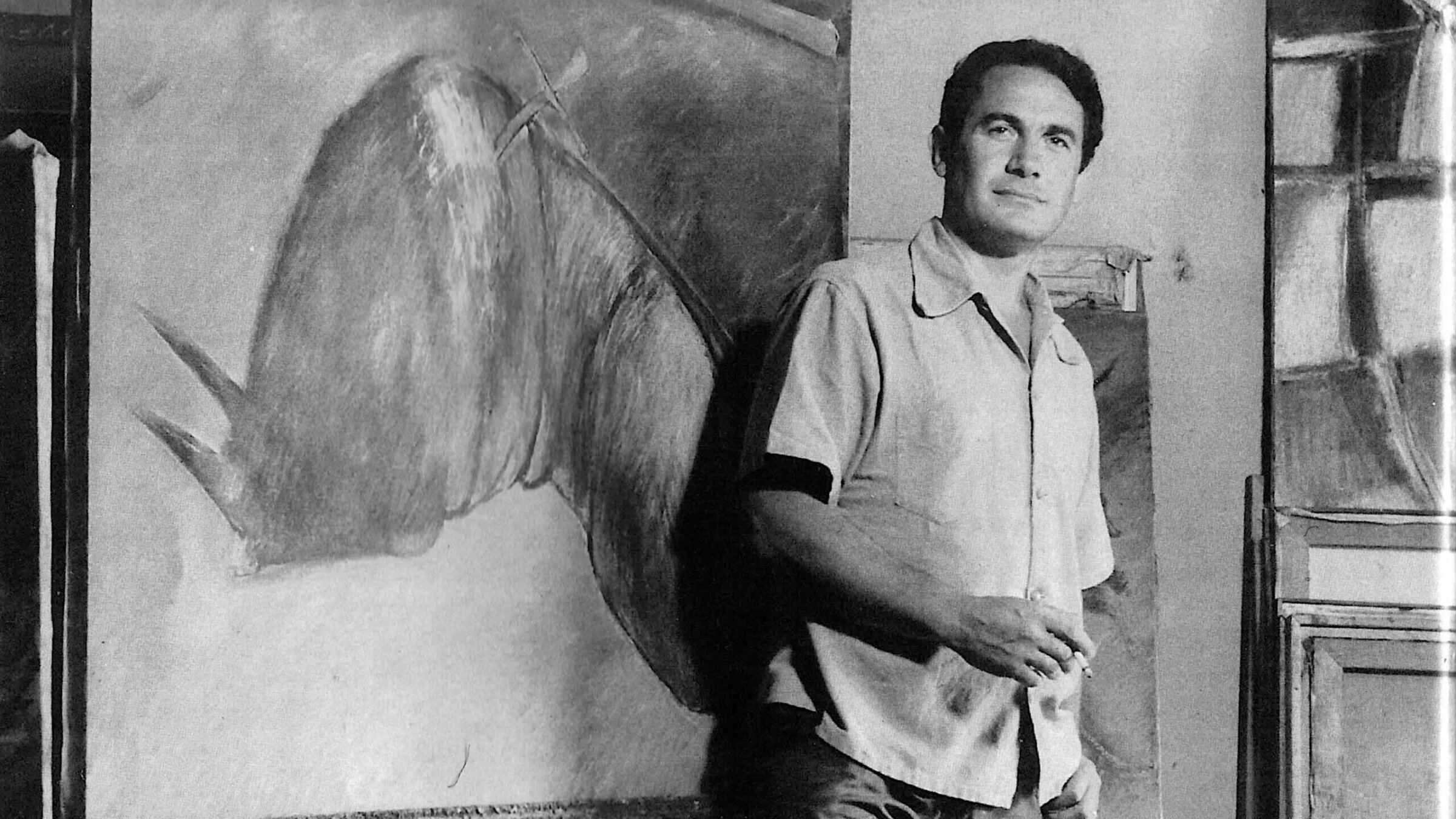

Yonia Fain in his Brooklyn studio, 1954 Courtesy of the artist

Paul Cézanne was a French artist. Pablo Picasso was a Spanish-born artist who chose to work in France. But what about modern Jewish artists who were forced to move from one country to another because of antisemitism? Do artists who had to flee repeatedly (many of whom were murdered by the Nazis anyway) have a home? Where, if anywhere, do they belong in the annals of art history?

The exhibition Modern-ish: Yonia Fain and the Art History of Yiddishland, on view through Dec. 9 at the City University of New York Graduate Center’s James Gallery, explores these questions, using the life of painter and Yiddish poet Yoni (Yonia) Fain (1913-2013) as an example. Modern-ish aims to provide a lens for examining the issue of Jewish artistic (non-)belonging. It exposes the weaknesses of the art world in dealing with the complexities of refugee artists. But it also proposes a new and exciting way of thinking about Eastern European Jewish artists — and of giving them a home at last.

It’s not surprising that millions of Jews left Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Pogroms were becoming more frequent, and a growing number of professions barred Jews from making a living. Jewish artists faced not only these conditions, but also troubling restrictions on attending art schools and limited opportunities for exhibiting their work. Many aspiring artists gave up and decamped for the more cosmopolitan cities of Berlin, Paris or New York.

As the Jewish situation across Europe deteriorated in the 1930s, artists were on the move again, seeking refuge in many parts of the world. Several passed through Asia on their way to safety. Some who survived the death camps made their way to Israel. One way or another, large numbers of Eastern European Jewish artists lived significant portions of their lives in countries where they had not been born.

Everywhere Jewish refugee artists went, they contributed to the development of modernism — a movement in which artists used new imagery and techniques to reflect the experience and values of modern industrial life.

Many of these Jewish artists flourished in their new homes, but often on the sidelines of the mainstream art establishment. They had one foot in their new cultures and one foot in their Jewish “otherness.” Even in Israel, Yiddish-speaking artists faced pressure to speak only Hebrew. Eastern European-born Jewish artists never found unqualified welcome anywhere.

Jewish modernists are often excluded from artistic narratives in both their original and adopted countries. There are very prominent exceptions, like Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine and Amedeo Modigliani. But most Jewish artists are not part of mainstream art histories. Reasons for overlooking Jews are complex, and can get entangled in political and social tensions that really aren’t about Jews themselves (like the complexities of ethnicity and identity in Eastern Europe, and ways that Eastern and Western Europeans perceive each other and themselves). Sometimes Jews are the center of debates and discussions, and other times they’re casualties of larger issues.

A consistent problem for Jews is the way that art tends to be defined by nations. Museum labels give artists’ names, dates of birth and death, and nationality. Art historians usually specialize in a national style (Italian Renaissance, French Impressionism). But the Eastern European Jewish historical experience is not a good fit with this nation-based system.

Jews born in Russia, Poland, Lithuania, etc. were not simply Russians, Poles or Lithuanians. They considered themselves Jews living in those lands. Ethnic Russians, Poles, Lithuanians, etc. didn’t perceive Jews as fellow countrymen, but as Jewish outsiders residing among them. And when these generations of Eastern-European-born Jews settled in Western Europe or outside Europe, they were still seen as Jews. Some places were more welcoming than others, and each individual’s experience was unique. But no matter where these Jewish artists ended up living, they were generally perceived as Jews first, and members of their new countries second.

But labeling a Jewish artist in a museum or art history book as “Jewish” is confusing, since Jewishness isn’t a nation. Pointing out an artist’s Jewishness can also feel uncomfortably “othering.” And yet, lumping Jewish artists together with non-Jews as “Polish” or “French” or “American” fails to capture the complexities of the Jewish relationship to nationhood. Hyphenated identities (Jewish-Polish, Russian-Jewish) are messy and unhelpful, and create more problems than they solve.

Modern-ish at CUNY proposes a radical way of working around the art world’s preoccupation with nations. The exhibition is the brainchild of conceptual artist Yevgeniy Fiks and James Gallery curator Katherine Carl. Fiks, Carl and colleagues around the world are working to promote an alternative conceptual “homeland” for Eastern European, Yiddish-speaking refugees born before World War II: an imaginary “country” without physical territory or borders known as Yiddishland. The art history of Yiddishland focuses specifically on the visual arts “in” the Yiddish homeland.

To be clear, the art history of Yiddishland is a mindset, an inclusive way of looking back at Yiddish-speaking artists and facilitating conversations about them in today’s art world. Rather than fixating on what made these artists different, it emphasizes what united them. In their multilingual and multinational lives, the one constant was Yiddish: its words, folklore, visual traditions and literature. Yiddish culture gave them a “homeland” of the mind and spirit — a portable country that they carried inside them wherever they went. Yiddishland was different for each “citizen,” depending on where they lived and which other languages they spoke. But the “capital city” of Yiddishland was always the language itself.

Few artists exemplify Yiddishland more clearly than Yonia Fain. His life and creativity defied traditional boundaries. He was equally a visual artist and a Yiddish poet, achieving great success in both. He was uprooted repeatedly, spending time in a bewildering variety of cities and countries over a period of 30 years.

Originating in Kamenets-Podolsk, Ukraine (then the Russian Empire), Fain’s family fled political and religious persecution when he was 10. He spent his youth and early adulthood in Vilnius and Warsaw. When the Nazis invaded, he escaped to Kobe, Japan — via Vladivostok and Siberia in the Soviet Union — thanks to an illegal visa signed by Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara. He was later transferred to the Ghetto in Shanghai, China.

After the war, he emigrated to Mexico, where he worked with the prominent painter Diego Rivera. New York became his permanent base in 1953, when he was 40 years old. He taught art at Hofstra University, which owns most of his surviving artworks and shares them on its website. He had many exhibitions in New York, and received numerous accolades as a Yiddish poet. His paintings and poetry often grapple with brutality committed against Jews.

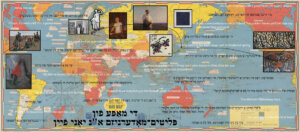

Despite his success as an artist, Fain is almost unknown today outside Yiddish cultural circles in New York. Hofstra handles his legacy with exemplary sensitivity, but many museums would be stumped by him. What does one do with a Ukrainian-Lithuanian-Polish-Soviet-Japanese-Chinese-Mexican-American artist who was actually none of those things, but instead a Yiddish-speaking Jew? One of Yevgeniy Fiks’ own conceptual pieces, Yonia Fain’s Map of Refugee Modernism, makes this point visually, plotting Fain’s journeys on a world map, interspersed with quotations by Fain about displacement. The map, as an illustration of Fain’s internal Yiddishland, actually depicts his homeland.

Seeing Fain and others like him as artists of Yiddishland gives them a voice in today’s art world — an equal voice with artists from traditional geographical countries. The potential for art history is enormous: bringing Yiddish-speaking modernists into the light will greatly enrich understanding of the movement. The thinking behind Yiddishland also has potential for non-Jewish refugee groups, past and present.

In summer 2022, Fiks and Maria Veits co-created the “Yiddishland Pavilion” at the 59th Venice Biennale, a major contemporary art event in Venice, Italy. Biennale pavilions are, unsurprisingly, organized by nation. The Yiddishland “pavilion” had no physical location, but was instead a series of “interventions” designed to draw attention to the exclusion of Yiddish-speaking artists from nationalist spaces. Yonia Fain featured prominently in these interventions. The CUNY exhibition gives New Yorkers the chance to see his work and pay tribute to the brilliant creative minds of Yiddishland.

The exhibit Modern-ish: Yonia Fain and the Art History of Yiddishland is on view at CUNY’s James Gallery through Dec. 9, 2023. The gallery is open Tuesday-Friday, 12-6 p.m. A literary evening in honor of Yonia Fain will take place at James Gallery Oct. 11 at 6:30 p.m.