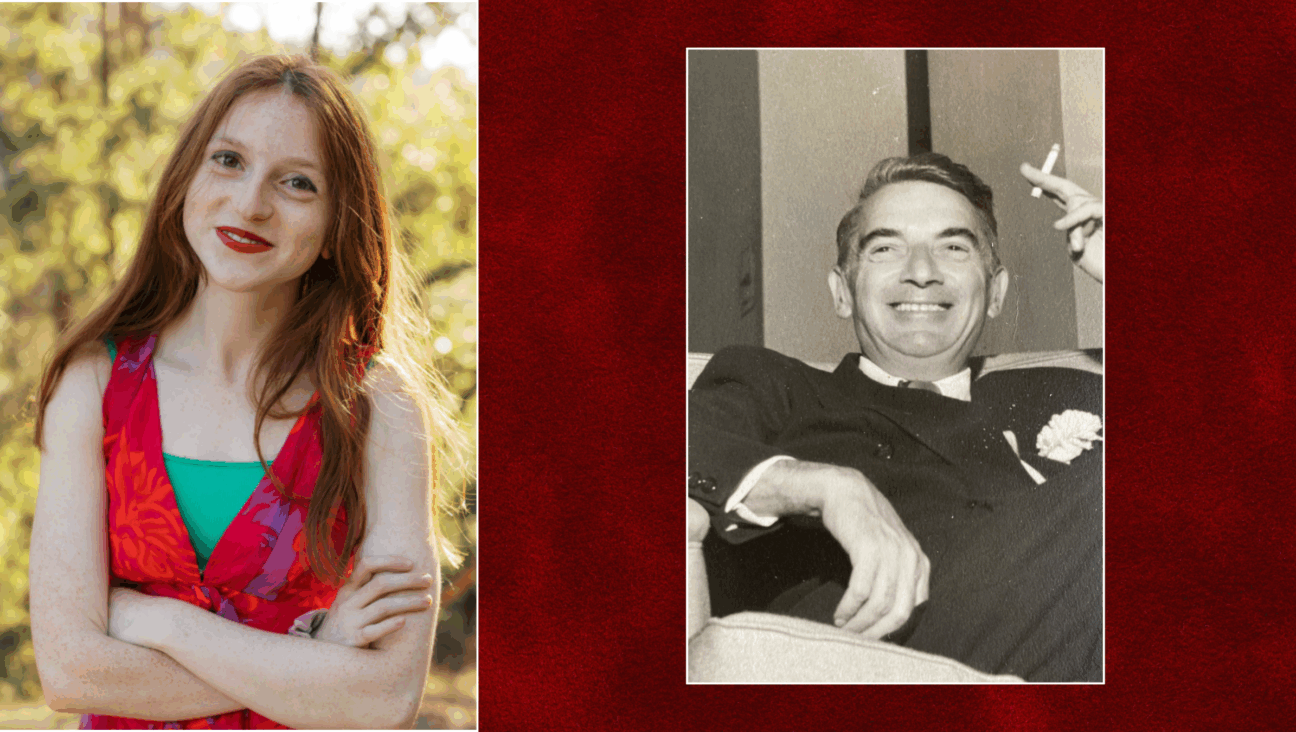

FICTION: Writer Yonia Fain’s haunting story about the painter Johannes Vermeer

The short story, here in English translation, allows us a peek into the mind of the renowned refugee writer and artist

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

This past spring, when the world was abuzz with the Vermeer exhibit in Amsterdam (and people I knew were actually buying plane tickets, or at least contemplating it), another exhibit was being conceptualized here in New York — Modern-ish: Yonia Fain and the Art History of Yiddishland. Fain was more than just a painter. He was also a Yiddish poet and short story writer. It occurred to me then that now was the time to translate Fain’s story “Johannes Vermeer” and link these two painters, despite the deep differences between them. Vermeer’s paintings reveal a world that seems luminous and very much intact, while Fain’s paintings and writings are mainly about the Holocaust and the ensuing dislocation and rootlessness.

Born in Kamyanets-Podilsky in 1913 or 1914, Fain moved with his parents to Warsaw and then Vilna to escape political unrest. As a young man he studied art and became involved in the Jewish Labor Bund. He often referred to himself as having lived with and been a witness to history, and his art and writing reflect that.

During the war, Fain sought refuge in Kobe, Japan, and then in Shanghai, China for six years. There he painted and wrote poetry. Wanting to paint murals he emigrated to Mexico in 1947. There he attracted the attention of the artist Diego Rivera who arranged an exhibit of his paintings at the prestigious Palacio de Bellas Artes. In 1953, he married an American journalist, Helen, and the two came to New York where he became a professor of art and art history at Hofstra University. At the same time, he achieved prominence as a Yiddish writer, publishing both poetry and prose. In 1991 he won the Manger Prize, the most coveted award in Yiddish literature.

In an interview for the film Yoni Fain: With Pen and Paintbrush, 2018, produced by the League for Yiddish, Fain discusses his story “Johannes Vermeer.” “The protagonist in my story is the son of a refugee, because in my book ‘Nyu-Yorker adresn’ (‘New York Addresses’), there are many children of survivors and they’re looking for an answer to history.” Despite his father’s protests, this young man traveled to Vienna to study one of Vermeer’s paintings and through his obsession with Vermeer sought an answer, not just to history, but to his own unhappy, lonely life.

Because Fain was both a painter and a Yiddish writer, it’s fitting that these two mediums by which he expressed himself should come together at a literary evening on Wednesday, Oct. 11 at 6:30 p.m. at the James Gallery of the Graduate Center CUNY in Manhattan. The program will feature bilingual readings and commentary on Fain’s poetry and prose by Shane Baker, director of the Congress for Jewish Culture;, Professor Elazar Elhanan of the Jewish Studies Program at City College and myself. For more details on the event, click here.

The exhibit can be viewed until Dec.9, 2023.

Johannes Vermeer

by Yonia Fain

More than once he had tried to put an end to his senseless and convoluted plan, but despite all efforts it never worked out for him. The plan, like a shiny, dark green plant, grew and blossomed in the hidden, shadowy depths of Ben’s mind. Finally, he stopped resisting. The joy of expecting something unusual had conquered all fears.

So what exactly was this plan?

Anybody who might have gotten to know Ben a little better would have found a way of understanding, or at the very least, a word of approval for the plan. But nobody knew Ben, and what’s more, he didn’t generally exist for anyone and if, on any given day, he would have disappeared from the face of the earth, nobody would have noticed.

A person who doesn’t exist for anyone has doubts from time to time as to whether he exists at all, and Ben was, in this case, no exception. The plan which was meant both to please him and put him in danger, was, ultimately meant to convince him of the living, concrete part of his existence — things that don’t exist, can’t take pleasure in anything and can’t be objects of punishment. The breaking of the restraint was, therefore, no less important for Ben than attaining the goal.

Ben’s plan was connected to the big city art gallery. This world-famous institution was located in a huge building filled with lecture halls, galleries, rooms of various sizes, chambers, corridors, narrow and wide staircases, auditoriums and spaces that were simply concealed, whose function no one knew, because they didn’t appear on the map of the museum.

In one of the half-lit corridors there was a door that had taken on a special meaning for Ben. Several times he had noticed unusual human figures coming out of it. After seeing them a number of times he decided to follow them, but each time they disappeared into thin air. Although he well knew that this was impossible, he couldn’t free himself of the impression that they had entered into the paintings on the wall.

Certainly, the whole thing made no sense, but then, does everything that happens in life have an explanation?

Ben had noticed several times that certain subjects and figures disappeared from the paintings and then, after the ebb and flow of two or three weeks, appeared again.

He tried several times to open the special door, but it was bolted and wouldn’t budge. When he put his ear to the surface of the door, the echo of a far-off heated conversation reached him. Ben was almost certain that the people were speaking Dutch.

According to the plan that was emerging in Ben’s mind, like a wonderfully fantastic plant, he had to stay in the museum overnight. Alone in the darkness in the abandoned spaces he would be able, without any difficulty, to open the lock and sneak into the room.

The best place for hiding out was a big Renaissance chest under a painting by Tintoretto.

Sunday was the best day to execute this plan because the museum was full of visitors and, as a result, the guards were more tired than usual.

* * *

When Ben saw the figures leaving the “Dutch Room” (that’s what he called the room on the other side of the special door) for the first time, he took them to be actors. But actors had absolutely no reason to disappear suddenly, and they also couldn’t enter and leave the surface of the paintings. Ben tried to inquire of the guards what these visitors in Dutch costumes were doing at the museum, but the guards shrugged their shoulders. They hadn’t ever heard of such visitors. Finally, Ben had to make peace with the idea that the secret figures appeared only to select guests and that he was one of them.

According to their clothing, their bearing and their effect on the surroundings, the figures belonged to the Dutch 17th century, the world of Vermeer and Spinoza. Maybe feelings have no colors and lines, and maybe one’s stream of thoughts doesn’t have any physical borders, but in order to give shape to his feelings, man creates art and in order to know what he’s thinking, he builds irrigation systems that don’t allow the stream of thoughts to spill out and dry up.

The light of Vermeer’s paintings illuminated the New York chaos and revealed for Ben the noble composition that endures permanently. What Vermeer showed clearly, Spinoza interpreted on a fundamental level:

Every idea is about something and that particular something is the body of the idea. The body of Vermeer’s pictures is the fundamental idea of Spinoza’s philosophy.

On the basis of Vermeer, Ben accepted Spinoza’s postulate, that God is thought and the world is His body, the physical element of His thoughts.

Ben was not a philosopher, he was a trained art -historian, and Spinoza only served

as a weighty argument in his master’s thesis about Johannes Vermeer.

He loved the great painter as only a lonely person could, and he took the appearance of Vermeer’s figures before him as confirmation that the Master of Delft had started to repay him with a quiet, and as was his way, delicately measured friendship.

Ben felt compelled to speak with the figures.

* * *

It was Sunday and Ben found himself in the museum. He could spend hours among the few Vermeer paintings: a chair, a map, a hanging oil lamp, a letter half-read, a woman half-awake, a curtain half-opened, a fragment of a wall with several pictures —windows to the landscape of the human spirit: he absorbed this all into himself. The border between himself and that world disappeared.

From the Vermeer room he went over to the Renaissance chest. He tried to open the lid, not in order to crawl into the chest — for that it was still too early — but only to find out if he had enough courage to do it. A guard noticed him and warned him he better not try it again.

Ben went back to Vermeer, and stopped near the “Allegory of Faith.” Of the forty some pictures that the artist had painted during his short life, “The Allegory” was, in Ben’s opinion, the weakest. He wondered how the master could have left the canvas with so many worn-out symbols. Even the snake on the too shiny floor looked like an imitation.

(By the way, several times during the past year, the snake had not been in the painting).

During his university years, Ben had analyzed the picture in one of his papers. There he tried to show that the master was not capable of painting on a traditionally religious theme. God lived for him, not in a story, but in His creation.

Ben stepped back from the picture and looked out into the hall. It was empty. Suddenly Ben decided that if he didn’t carry out his plan in the next twenty minutes he would have to give it up entirely.

An evening languor hung in the air. Not long ago it had been broad daylight and soon it would be night. Quickly, Ben drew closer to the chest and lifted the lid. Suddenly someone arrived and Ben didn’t even manage to lower it. But apparently, the stranger wasn’t much concerned. He was dressed in the uniform of a Dutch officer, his tall black hat with its broad brim almost completely hiding his face. With a movement of his hand he greeted the disconcerted Ben and continued walking in the direction of the “Dutch Room.”

Ben hastily got into the chest, carefully lowering the lid over himself.

* * *

Ben didn’t know how long he had lain in the chest. He had the feeling that he’d fallen asleep several times. His watch couldn’t help him because the dial wasn’t visible in the dark. Silence prevailed. The great museum was now alive, alone with itself. Ben just barely lifted the lid, a breezy freshness touched his face. He got out of the chest. The surroundings were illuminated by a weak yellowish light; only in the distance could a red “Exit” sign be made out. Ben made his way to the “Dutch Room” on his tiptoes. Suddenly he heard steps in the distance and paused. The steps, regular and confident, came closer. Ben went back to the chest and quickly lowered himself to the bottom. The steps kept coming closer, they reached the chest and continued going on their regular route.

In order to conquer his rapid, almost painful heartbeat, Ben decided to think about Vermeer. After all, it was because of him that he was here in this menacing and increasing darkness.

Ben’s master thesis was about Vermeer’s painting “The Studio.” The picture appeared in various catalogs under other names as well. But for Ben, only “The Studio” made sense. The tiniest area of the canvas lived in Ben’s memory. Because of this painting Ben had, with his few hard-saved dollars, traveled to Vienna. He had to see the original in the Vienna Museum of Art History with his own eyes.

ֿHis father, who had been dead now for more than eight years, could not comprehend why his son was going to Vienna. “How can anyone, in the name of art, forget about history?” he would continually argue. Ben’s assurance to his father that he wasn’t traveling to see the city but Vermeer’s “Studio,” didn’t help much. At the airport, his father forgave him everything. “Oh well,” he said. “Apparently, this is the way things are; one generation is not able to transmit its pain to the next.”

For Ben, the month in Vienna was divided in equal measure between difficult, muddled and sleepless nights and bright uplifting Vermeerish days.

In Vermeer’s painting “The Studio,” the artist was festively attired, sitting in front of a freshly started canvas, painting. On the left side, a little apart from him, deeper into the room, stood a young woman. The wall behind her was illuminated by a light that came in through a window, concealed from the spectator by a thick, richly woven curtain.

The young woman was dressed in a light blue outer garment. In her left hand she held, pressed to her breast with motherly tenderness, a thick book with yellow covers; in the right — a trumpet.

Like other Vermeer scholars, Ben assumed that the young woman was Cleo, the muse of human history. Cleo wore a laurel garland on her head and its leaves were the starting point of the picture. On a table, near the muse, there lay a great plaster mask which was reminiscent of Michelangelo’s David.

What did all these elements signify?

Ben had studied almost all the books that dealt with Vermeer’s iconography with great thoroughness, but none of them satisfied him completely.

Finally, Cleo’s smile brought him to Spinoza. It was a smile not of joy, not of resignation or acceptance — it was a smile of understanding.

The elements of Vermeer’s “Studio”: the book, which carries within it the facts of history; the trumpet, which heralds their glory and the mask, calling to mind their past, are permanent in their relationship. God is not, as Newton had believed, the first cause. No, He is, as Spinoza had proven, and as Vermeer had shown, the permanent cause.

In “The Studio,” Vermeer sat with his back to the observer. And that’s how it had to be. Fabritius, Vermeer’s teacher and Rembrandt’s student, had spoken a great deal about his master and his portraits. Without a doubt — the portraits were extraordinarily good. But the greatest portrait is not the face of the person, but the face of the picture. The world, as God’s portrait.

And he, Ben, who is a part of the world, is also a part of the permanent cause. He only has to find it within himself.

* * *

Ben detected the sound of several people having a conversation. One voice, deep and a little hoarse, came from a man who had to be getting on in years and was a heavy smoker. The second had a silvery, singing tone, and certainly belonged to a young person, maybe even a boy.

Ben lifted the lid a little in order to hear what they were saying. They were speaking in a foreign language, which meant that they were Dutch and that Ben did not have to be wary of them. He opened the lid and got out of the chest. The voices disappeared; only the silence rang in his ears.

Ben set out for “The Dutch Door,” found it quickly and tried opening it, but it was bolted. He then put his ear to its surface. A lively heated conversation was going on in the room. People were laughing, clinking glasses and singing in a drunken, carefree manner. Among the voices he even recognized the heavy smokey voice of an older man and the silvery laughter of a young man.

Ben knocked on the door several times, but, apparently, nobody heard him. They were too preoccupied with themselves. He didn’t want to knock more loudly, because he was afraid that the guards would hear him.

He took out a thin little iron device from his pocket and stuck it in the keyhole. It didn’t take him long to find the cylinder and he pressed on it several times, until it yielded. Ben gave the door a push and it started to open. Swiftly, he went over the threshold through a narrow opening. Almost simultaneously, two forces overtook him: the silhouette of a small table with two half-emptied glasses and a lute struck his eyes, and a wild sharp alarm suddenly began howling in his ears. Ben didn’t know where to disappear to. He wondered why the Dutch people who had been here a moment ago had run away and not taken him with them. Didn’t they know that he, just like them, wanted to become part of a picture — part of an absolute harmony?

When the guard hurled himself on top of Ben, he didn’t resist. He had nothing to defend. His tired body mattered to him now even less than usual and as to his spirit — the guard posed no threat to it.

“What are you doing here?” asked the guard after putting Ben in handcuffs.

“You wouldn’t understand,” Ben answered quietly.

* * *

When the detective at the police station finally attended to Ben, the steely gray of an autumn New York morning was already reflected in the window.

Ben was tired and didn’t know how long he had sat on the long wooden police bench that squeaked glumly at his every move. His watch no longer worked and his glasses had gotten lost somewhere. He thought about his cat that was at home alone and must be very hungry and lonely by now. He knew that people under arrest had a right to make a phone call, but did that law include making a call to a cat? Would the cat actually know that the call was coming from him? Maybe not, but the ringing would surely interrupt the lonely silence in the room.

“Come,” somebody suddenly ordered Ben. The figure took shape so unexpectedly before Ben’s eyes that he wasn’t sure if it was a figment of his imagination or an actual living being.

“Come, come,” the voice hurried him.

Ben went into a long, narrow room. Around a small table stood several chairs. The figure, certainly a detective, sat down on one of them and gestured with his hand for Ben to do the same. A second person entered the room and sat down behind Ben. The detective read him his rights.The room, the two large men, the table, the low ceiling, the dirty floor, the hard alien air — Ben knew all of this well from films. Now he had a role in such a film.

“I know what my rights are and I don’t need a lawyer to defend me.”

Somebody typed up his words. He didn’t see the person and wondered why.

“What were you doing in the museum?” asked the first detective.

“You know very well what I was doing: I was forcing open a door.”

“Why? What did you think you’d find there?”

“I know that I broke the law and I am ready to pay for that… but I’m not able to explain what I was doing in the museum… it’s too complicated… you wouldn’t believe me anyway.” Ben finished and wondered where he’d gotten so many words.

“Who do you know in the museum? Who informed you regarding what was in the room?” the detective persisted.

“I don’t know anyone and nobody informed me about anything. I just wanted to talk to Vermeer’s figures.”

“Who is Vermeer?” the detective wanted to know.

“A painter, a very great painter.”

“And what’s he doing in the museum at night?”

“He lives there as well as in other museums.”

“You mean to say that he eats and sleeps there?”

“He doesn’t eat and he doesn’t sleep, he just lives.”

“You mean to say that he lives on air and that he’s your friend?”

“Yes, he’s my friend.”

“And aside from this Vermeer, do you have any other friends? Do you have a wife?”

“No.”

“Children? Relatives? Anyone who knows you?”

“I don’t have anyone,” Ben answered.

“What is your occupation?”

“I have a small store. I make picture frames.”

“Whom do you meet with?”

“With no one. I live with myself.”

“Who do you write letters to from time to time?”

“No one. I don’t write letters.”

“Who do you talk to when you get tired of being silent?”

“To people…”

“Who are these people?” the detective began to lose patience.

“I speak to whomever happens to be around… I don’t ask their names… I don’t need to know that.”

“But why does Vermeer have a name? How is he different from all the other people?”

“He’s a friend… Only friends have names.”

“If this Vermeer is such a good friend, why didn’t he give you a key to his room? Huh? Why did you have to break in?” the detective yelled into Ben’s face.

“Maybe he wanted to test me?” Ben answered serenely.

“And you really want me to believe your nonsense?”

“Whether you believe me or not, doesn’t matter to me. I don’t mean to insult you. I’m ready to suffer my punishment… But I think that it’s none of your business what I think…”

“What does matter to you?” the detective yelled and stood up.

“At the present moment, nothing,” Ben said. Suddenly he remembered something and cried out, “It’s not true that nothing matters to me, it’s not true, something does matter to me.”

“And what is that?” the detective asked, half with mockery and half in astonishment.

“My cat is locked in my apartment… She must be very hungry by now… Send someone over with food… The cat doesn’t deserve to suffer for nothing.”

From somewhere the detective produced a long sheet of paper. His eyes quickly scanned the densely printed lines and then he shoved the sheet over to Ben and handed him a pen. Ben signed the document without reading it.

“The cat is completely innocent, she doesn’t deserve to suffer for nothing,” he muttered to the detective.

* * *

Ben woke up after a long, difficult sleep. He lay in a bed that he had never seen until now. The room was small, the window — covered with bars. The air — stagnant, with no echo. Ben threw off the flimsy blanket and saw that his body was clothed in a gray hospital robe. He got out of bed and ran to the door. It was locked. He rememberedabout the cat and began banging on the door with clenched fists. Nobody answered.

Ben went back to his bed and feeling lost, he sank down into the cold white muteness.

From the depths of his body, sobs struggled to the surface and arranged themselves in words.

“I am a form that cannot find its permanent cause,” his parted lips murmured. He was thankful to his lips for the words. Mesmerized, he listened to what they had to say.

“I am Vermeer’s unpainted picture, I am Spinoza’s geometrical method minus the content… Maybe the hospital is my museum? Maybe this illness is my talent?…”

At this, his lips locked. Ben touched them with quivering fingers. He wanted to hear more but the lips didn’t want to open.

Finally, Ben stretched out on the bed and fell right asleep.

* * *

When Ben awoke, he saw a tall man with a pointy beard, sitting on the edge of his bed.

“How are you feeling?” The stranger asked.

“I’d feel better if the door weren’t bolted.”

“Where would you go?

“I’d go feed my cat.”

“And after that?”

“You want to know if I would go to the museum again?”

The stranger nodded.

“No, I won’t go to the museum anymore,” Ben informed him.

“Are you afraid of getting arrested again?” the stranger asked.

“No, that’s not the reason,” Ben answered calmly. I don’t need to look for Vermeer anymore, he’ll find me in the hospital.”

“What do you want from Vermeer?”

“I want to ask him something.”

“But Vermeer is dead,” the stranger said.

“All the living live with the dead,” Ben answered.

“We live with their creations, not with them,” the stranger said and stood up.

“Their creations are their life,” Ben sat up as he said it.

The stranger sat down again on the bed and put his broad, hairy hand on Ben’s. It was a warm, kind hand, like the hands of the officers in Vermeer’s paintings. Ben lifted his eyes in order to see what the man was doing with the other hand. In it, he held a half-drunk glass of wine. Ben began to wonder why he hadn’t noticed until now that red drops of wine clung to the stranger’s mustache and that his full red lips were smiling. His three- cornered lightly dyed beard also smiled.

“Who are you?” Ben called out full of expectation.

“I’m your doctor.”

“Did Vermeer ask you to come?

“Why Vermeer?” the doctor asked and with his free hand wiped the wine drops from his mustache.

Ben thought for a moment and said, “Because Vermeer is my friend.”

Translated by Sheva Zucker