I.B. Singer’s many newspaper articles are now available in English

In his nonfiction work, Singer often portrayed himself as the sole guardian of the annihilated world of Polish Jewry

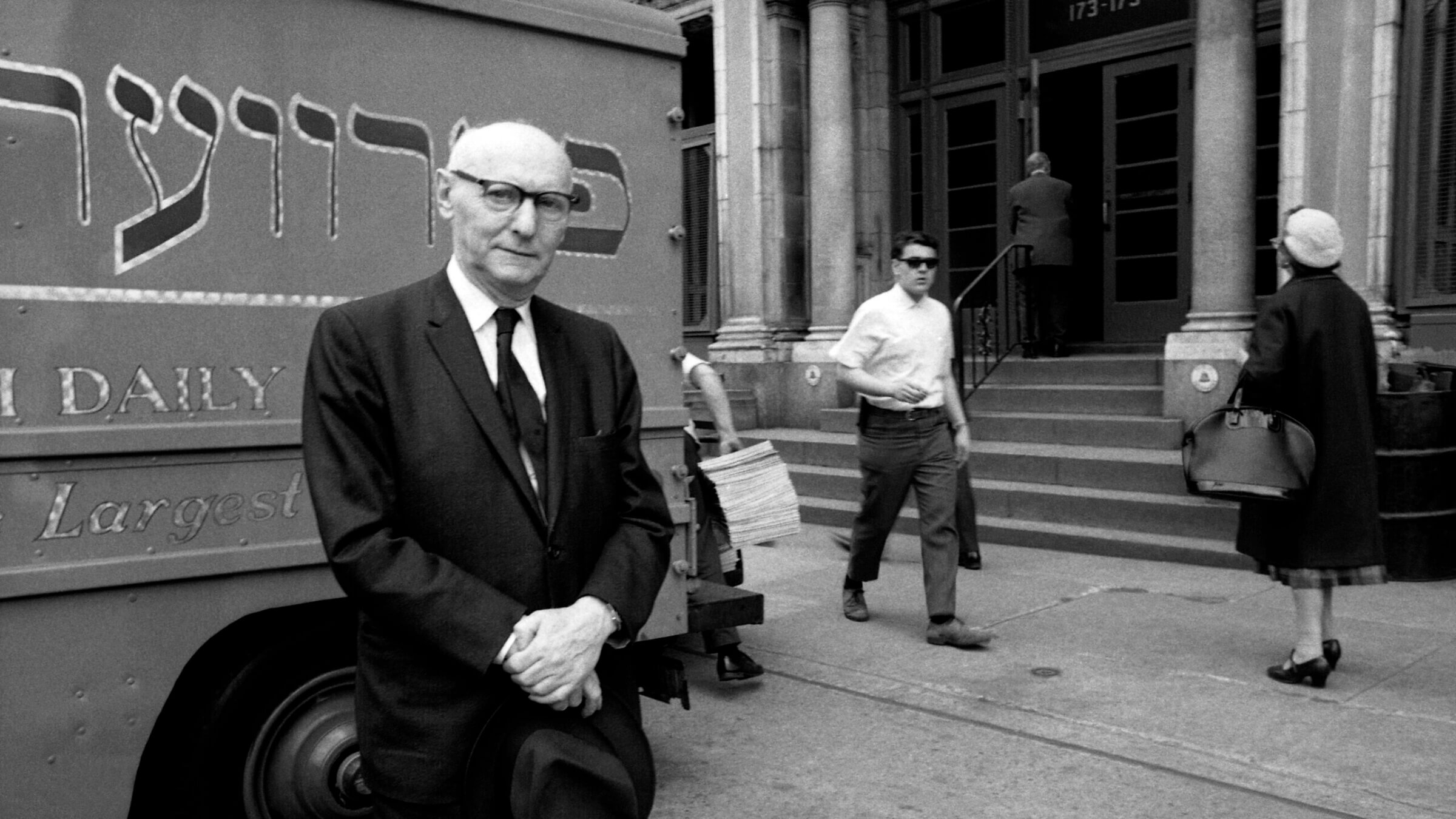

Isaac Bashevis Singer in front of the Forverts building in 1968. Photo by Getty Image

Most Jews don’t know that the Forward (known in Yiddish as the Forverts) published not only fiction by Isaac Bashevis Singer, but his essays too.

In fact, Singer used at least three pen names to differentiate between his fiction and nonfiction pieces. His literary works were under the name Yitskhok Bashevis, while the byline for his articles was Yitskhok Varshavski or D. Segal. In English, he was known as Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Writer David Stromberg, who has translated some of Singer’s literature to English, took on the comprehensive project of familiarizing an English-speaking audience with Singer’s nonfiction using the byline Yitskhok Varshavski. The entire collection will be published by the Yiddish Book Center’s White Goat Press in three volumes. The first volume, Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Writings on Yiddish and Yiddishkayt: The War Years, 1939-1945, has already come out and is available for purchase.

The years before World War II were difficult ones for Singer. When he arrived in the United States in 1935, he tried to find a niche in what was then a new literary scene. He wrote articles for the Forverts, but to the local Yiddish literari, he remained in the shadow of his renowned older brother, the novelist Israel Joshua Singer. It’s no surprise that he was bitter about this, and about the future of Yiddish in the United States and of American Jewry in general. In his articles, he reiterated the idea that Yiddish literature in the United States needed to derive its inspiration from older Eastern European sources, as there was no real Yiddish culture in the United States.

The destruction of Polish Jewry shattered Singer’s hope for a Yiddish revival in Eastern Europe. He compared the destinies of Yiddish and Hebrew. While Hebrew was being revived with the support of old literary texts, primarily the Bible, Yiddish was a vernacular that could only survive by people speaking it to each other. The Nazi genocide of the Jewish people robbed Yiddish of its source of life, making it the most challenging crisis in the history of the Yiddish language.

Singer suggested several radical solutions to rescue Yiddish language and its literature. He was angry at YIVO because the institution pursued academic linguistic studies instead of concentrating its efforts on encouraging Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe to continue speaking, reading and writing the language. Singer dreamed of a sort of Yiddish yeshiva, where Yiddish writers would learn about the Eastern European Jewish religious and cultural traditions. He wrote scornfully about American Yiddish literature, which in his opinion had no Yiddish sensibility, but didn’t name any of these authors. Stromberg writes that Singer’s writings from that period were “all infused with his personal perspective and experience.” Singer’s mother and younger brother Moyshe died around 1942 somewhere in Kazakhstan, after being sent there by the Soviets with the outbreak of the war. His older brother Israel Joshua died of a heart attack in New York in 1944.

Singer’s relationship with his sister Esther Kreitman, who lived in London, was not an amicable one. This gradually contributed to Singer’s self-image as the lonesome guardian of the treasures of the murdered world of Polish Jewry. In those years, the Forverts began to publish his serialized novel The Family Moskat, allowing Singer to begin fulfilling his mission of keeping the legacy of Polish Jewry alive. In this way, concludes Stromberg, the war years opened a new phase in Singer’s literary career.

Contrasting with the Yiddish literary mainstream, Singer didn’t have any leftist political tendencies — not in Poland, nor in the United States. His conservative worldview influenced not only his attitude to Yiddish culture, but also toward American Jews, whom he considered ignorant. Singer wrote stories about older mystical beliefs like dybbuks using contemporary psychological concepts for his American audience. In some articles, notes Stromberg, Singer foreshadowed his future work. For example, in an article about Hanukkah, the character escapes the Holocaust by disguising himself as a simple Polish peasant. Later, that character was developed into the hero of the book The Slave.

Stromberg adds a short introduction to each article explaining the importance and meaning of each text. These explanations are useful for readers to better understand Singer’s thought process and artistic evolution. Not all of Singer’s articles were at the same artistic or intellectual level as his literary works. This was possibly why he wrote his articles under a pseudonym. It would have been useful to read an actual critique of his journalism. Certain articles of his seem to have been written in a hurry in order to meet deadlines.

In his articles, Singer doesn’t seem to be a reliable or fair critic of American Yiddish literature. His writing creates the impression that there were no significant American Yiddish writers. According to him, none of the works by Sholem Asch, Joseph Opatoshu, David Ignatoff, Baruch Glazman or any other popular writers of that era had any substance. Singer’s articles actually reveal a person alienated from his American Jewish environment. But over time, Singer developed a persona for himself as the sole living inheritor and caretaker of authentic Yiddishkeit. This strategy turned out to be a successful one, especially in the eyes of his English-speaking readers. Thanks to Stromberg’s translations, we can see the first signs of Singer’s evolution into this role.