You can now hear people speaking Yiddish in bars all over Berlin

A Yiddish conversation group meets biweekly at locations around the city. Other people think they’re speaking Swiss German.

A Shmues un Vayn meeting at KAPiTAL bar in Neukölln, Berlin, in April 2023. Photo by Christian Kehrt

At a Berlin bar on a recent Wednesday evening, several patrons kept glancing curiously at the group of eight people around a neighboring table. The members of the group were chatting in a language that’s almost, but not quite German.

Someone approached the group and asked what language they were speaking. “Is it Plattdütsch?” they guessed. “Swiss German?” The answer came as a surprise: Yiddish.

Since early 2022, the shmueskrayz, or conversation group, has been meeting every two weeks in bars around Berlin. On an average night, anywhere from six to 14 people might show up. More formal events, like a Yiddish Purim-shpiel and a summer block party, have drawn dozens.

In warm weather, the group sits outside the bar, cafe-style.

The average gathering includes native speakers of English, German, Hebrew, Russian, Dutch and often several more languages. Some have advanced degrees in Yiddish studies, while others studied the language for just a few months on Duolingo.

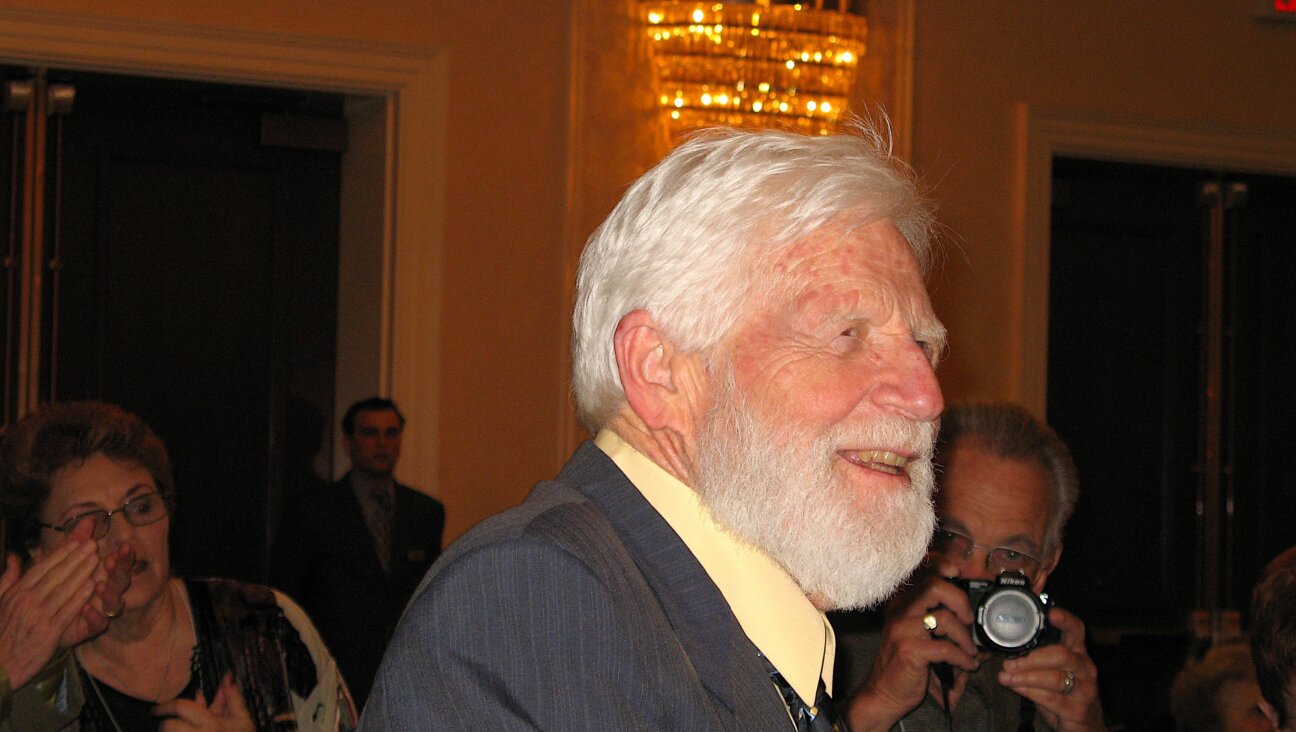

Founded by Yiddish translator Jake Schneider through the loose cultural collective Yiddish.Berlin, the group offers an opportunity to speak Yiddish casually, outside of formal classes. Schneider told me that, after studying Yiddish online throughout the pandemic, “I wanted to find my Yiddish-speaking community.”

Via Yiddish.Berlin, Schneider got in touch with Katerina Kuznetsova, a Yiddish instructor and poet. Their first meeting was Schneider’s first-ever in-person conversation in Yiddish. “It was really weird,” he remembers. “I didn’t know how to say, like, ‘a cup of tea,’ because I’d just been sitting on the internet.”

The first meeting of what would come to be called Shmues un Vayn (Chat and Wine) took place a few weeks later. Early gatherings were small and conversation was halting. Soon, though, word about the group began to spread. By the time I came to a shmues (chat) in autumn 2022, Shmues un Vayn had a core of a dozen or so regular members. The group’s mailing list now has 90 people.

Shmues un Vayn gatherings don’t have specific themes. Instead, conversation flows freely, with less confident Yiddishists learning from more advanced speakers. At some get-togethers, the group plays Yiddish card games that a member once brought back from an Orthodox store in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and the evening often ends with singing Yiddish songs. “It’s very simple and natural,” says Kuznetsova. “You don’t need money for this, you don’t need funding. We gather and speak Yiddish and have fun.”

Schneider recently led an online presentation hosted by KlezCalifornia (now available on YouTube), where he shared advice on how to launch an in-person Yiddish conversation group. He admitted that the Berlin model wouldn’t work for everyone. In some areas, meeting in bars might be too expensive, or longer travel distances could make weeknights difficult. Instead of advising his viewers to copy the Shmues un Vayn model, Schneider encouraged finding a format that works for a specific community. That might mean meeting in a member’s home or planning around school schedules.

Schneider also shared tips for getting fellow Yiddishists to show up. At Shmues un Vayn, for example, every meeting includes taking a photo of the attendees to be posted in the shmueskrayz group chat. One goal of the picture, Schneider admits, is to give those who stayed home a twinge of FOMO (fear of missing out) and hopefully encourage them to join next time.

The group has even come up with a Yiddish term for FOMO — farfel-moyre. It’s one of several Yiddish phrases its members have coined. At the same time, members also borrow words from their mother tongues in their Yiddish conversations.

“It’s a secular Yiddish of the 2020s, a Yiddish for linguists, readers and writers, academics and creatives,” said one member, Irad Ben Isaak. Translator and poet Jordan Lee Schnee sees this borrowing of words and phrases as a natural development of the language. “If you read, like, Itzik Manger, he’s using all these Romanian words,” he points out. “We don’t need to be so pure about it.”

Interestingly, several Shmues un Vayn members who had taken formal Yiddish courses before joining the group, said that initially, after so much text-based study, it felt “unnatural” to make the leap to casual conversation. German-born photographer Arndt Beck was reluctant to speak Yiddish to other students in the Yiddish language course he had taken before joining the group. But after two years of coming to Shmues un Vayn, he says there are now people with whom he speaks Yiddish “automatically.” In fact, when I interviewed him in German for this article, it was the first time I had heard him speak anything other than Yiddish.

One of the most striking effects of these get-togethers is its influence on members’ casual use of Yiddish in everyday life — something that’s rare now outside of the Hasidic community and small Yiddishist circles. Several group members now use Yiddish to speak and write to each other all the time, even when they’re not at a shmueskrayz.

Holding these gatherings in public and in different locations also makes Yiddish “part of the fabric of everyday life” in Berlin, Schnee said. Anyone is welcome to join, whether as a one-off or every time. “It’s allowed us to take over the city in a way,” he added.

Ben Isaak agrees. “I think every town needs one,” he said.