Why do so many Yiddish words in English have a German spelling?

The small but important differences in how we spell Yiddish words today

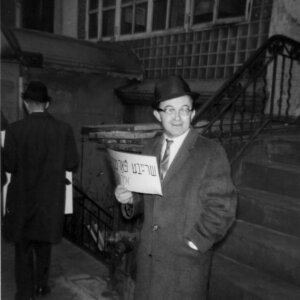

The 1970 Yiddish newspaper protest Courtesy of League for Yiddish

So, do you spell it schlep or shlep?

And why does it matter?

The answer to this seemingly innocuous question that comes up again and again involves the Jewish Enlightenment, Jewish diaspora nationalism, and a little-known protest in front of the Forverts building in 1970.

But before we get into all that, here’s a little background:

Yiddish as ‘corrupted’ German

Yiddish first developed in medieval Alsace-Lorraine, on the modern French-German border, as a blend of medieval German, Hebrew and Aramaic, and developed in parallel with Modern German. As it migrated eastward, it picked up elements of Slavic languages.

Beginning in the 1770s, the Jewish Enlightenment known as the Haskalah arose in Germany. Reformers like Moses Mendelssohn saw Yiddish as a “corrupted” version of Modern German that supposedly prevented Jews from integrating into mainstream society. They preferred writing in Hebrew instead.

The influence of the Haskalah nearly eradicated the Western Yiddish of Germany, but it had a different effect on the Yiddish of Eastern Europe, both promoting it and “Germanizing” it at the same time.

Ironically, the rise of Yiddish literature in the mid-19th century in Eastern Europe was introduced by those very advocates for the Haskalah who perceived the Yiddish language negatively. Frustrated that their books in Hebrew were selling poorly, writers like Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem switched to Yiddish in an attempt to reach the masses and found considerably more success.

Instead of convincing Jews to speak German, writers of this era sought to “civilize” the Yiddish language by introducing words from supposedly more “sophisticated” languages like German and Russian. An early member of this literary movement, Isaac Mayer Dick, would even explain German and Russian words to his readership in parentheses.

Spelling Yiddish like it’s German

Even if most Yiddish speakers didn’t use many German words when speaking Yiddish, those Jews who wanted to signal their education wrote with its heavy influence. They also spelled many Yiddish words as if they were German.

This treatment also affected the transliteration of Yiddish words into English. This is why shlep came to be spelled in English as schlep, based on the German spelling system that used ‘sch’ to make a ‘sh’ sound.

When Yiddish-speaking immigrants came to the United States, they began using Modern German in their written Yiddish and German spelling conventions in Yiddish and in English letters. Hence schlep, kvetch, schmooze, mensch, etc.

‘Write like you speak’

The usage of Modern German words in Yiddish was also embraced by the Forverts, which was founded in 1897. The name “Forverts” is itself not a Yiddish word. (The real Yiddish word for “forward” is foroys.) The original masthead even transliterated it as Vorwärts, a German name taken from the Social Democratic party newspaper of Germany. Like its forerunner, the Forverts represented socialists in the United States.

Unfortunately for the founder and editor Ab Cahan, this flooding of German words into his Yiddish newspaper resulted in a small readership, since only “educated” readers understood German. So he began looking for new writers who wrote Yiddish the way that ordinary Jews actually used it. “Write like you speak” was the order he gave to new journalists, as recounted by Forverts editor Hillel Rogoff in his memoir of the newspaper Der gayst fun forverts (“The Spirit of the Forverts“). Cahan demanded a “yidishn yidish” from his new writers, an expression he invented for a purer Yiddish.

But even with fewer Modern German words, the Forverts’ spelling and transliteration remained consistently Germanized for decades, as it was for competing newspapers.

The emergence of Jewish diaspora nationalism

In the late 19th century, a form of Jewish diaspora nationalism emerged with a specific goal of standardizing and distinguishing the Yiddish language as the honored tongue of the Ashkenazi Jewish people. This effort was punctuated by the Czernowitz Conference of 1908, where Yiddish was declared a national language of the Jewish people, alongside Hebrew.

Ber Borokhov, a political thinker and philologist, wrote an analysis in 1913 declaring that the conception of Yiddish as a “corrupted German” is not factual and must be resisted. His concept was part of the basis upon which YIVO (the Yiddish Scientific Institute) was founded in 1925 in Vilna (now Vilnius), Lithuania.

After YIVO’s main branch was relocated to New York City in 1940 during the breakout of World War II, it continued its scholarly work under the eye of linguist Max Weinreich. His efforts to standardize Yiddish and match its spelling — and critically, its English transliteration — bore fruit with his son Uriel Weinreich’s 1949 Yiddish textbook College Yiddish and his and Mordkhe Schaechter’s 1961 Guide to the Standardized Yiddish Orthography.

One of these three scholars’ goals was to urge Yiddish writers to avoid using daytshmerish, a derogatory term for a style of speaking and writing Yiddish with many borrowings from Modern German. The reference books they put together also standardized English transliteration to reflect the actual sound of the word, not the Germanized spelling.

‘Somebody threw an egg at us’

The Forverts, and its competitors, nonetheless continued to use German-influenced spellings for nearly a century, even as YIVO promoted a new standard. In the shadow of the Holocaust, it was an especially charged issue to declare Yiddish linguistically and culturally independent of German.

Yiddish scholars led by Mordkhe Schaechter insisted on spelling reforms, leading protests at both the Forverts and at Der Tog, which folded in 1972. (Both papers were conveniently located in the same part of Manhattan.)

Schaechter’s daughter and current Forverts editor Rukhl Schaechter recalled going to the demonstration that her father led outside the Forverts Building in 1970: “The Forverts staffers were very upset. They were yelling at us from their window, and somebody threw an egg at us.”

The Forverts gave in, recognizing that they needed to write in the Yiddish that new speakers would be accustomed to. About 10 years after the protest, there were marked changes in their spelling.

The word for space should be ‘kosmos,’ not ‘speys’

The aim of these protests was not merely to rid the newspaper of German influence, but also the pervasive English influence which had emerged in the language. Activists derisively called the heavy English usage “potato Yiddish.”

Mordkhe Schaechter’s nephew and former Forverts deputy editor Itzik Gottesman recalls wearing a sign with the word speys (“space”) crossed out and the word kosmos written under it.

YIVO’s standard is not universal

While Yiddish at the Forverts and in the secular world has standardized according to YIVO’s reforms, both in Yiddish and in English transliteration, this is not universal. Hasidim, who make up the bulk of today’s Yiddish speakers, have not followed YIVO’s language reforms — their Yiddish spelling and English transliterations continue to follow other conventions.

However, to most readers, the differences between Yiddish-origin English words and the Yiddish words are more common in day-to-day life.

Upon their entry into English, many Yiddish words were used by English speakers for their derivative expressions, not their primary meanings.

For example, kvetch means “complain” as an English word, but its primary meaning in Yiddish is “to press.” Likewise, mensch means “decent person” as an English word, but its primary meaning in Yiddish is “person.”

And finally, schlep and shlep are synonymous, meaning ‘to drag.’

However there is a key difference between the two: with the English schlep you can write, “I schlep to Manhattan to get to work,” meaning drag yourself, but you can’t write the Yiddish shlep in this circumstance because dragging yourself in Yiddish is reflexive, requiring the extra word zikh: shlep zikh.

So the next time you see a Yiddish word in a sentence, ask yourself: “Is this really Yiddish? Or is it English?” Chances are, if it looks like a German spelling to you, it’s probably English.