Rise in anti-Zionism forces journalist to rethink his leftist Jewish identity

Michael Gawenda’s autobiography is a useful guide on how to navigate difficult conversations about Israel and Zionism

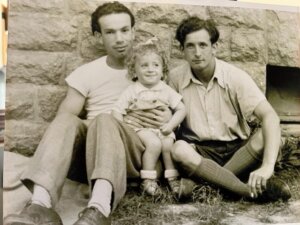

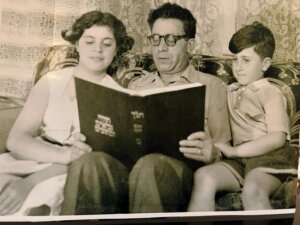

Courtesy of Michael Gawenda

Read the original Yiddish version of this article here.

Michael Gawenda was shocked to see what his friend was publishing about Israel.

In his autobiography “My Life as a Jew,” the prominent Melbourne-based journalist Gawenda describes how he broke off a long-standing friendship with a colleague who, he says, had signed an open letter accusing Western journalists of biased reporting on the situation in Israel, and had agreed to publish a book claiming that the “Israel lobby” silences anything that criticizes Israel. The incident, he claims, led him to reconsider his relationship to Zionism and the State of Israel.

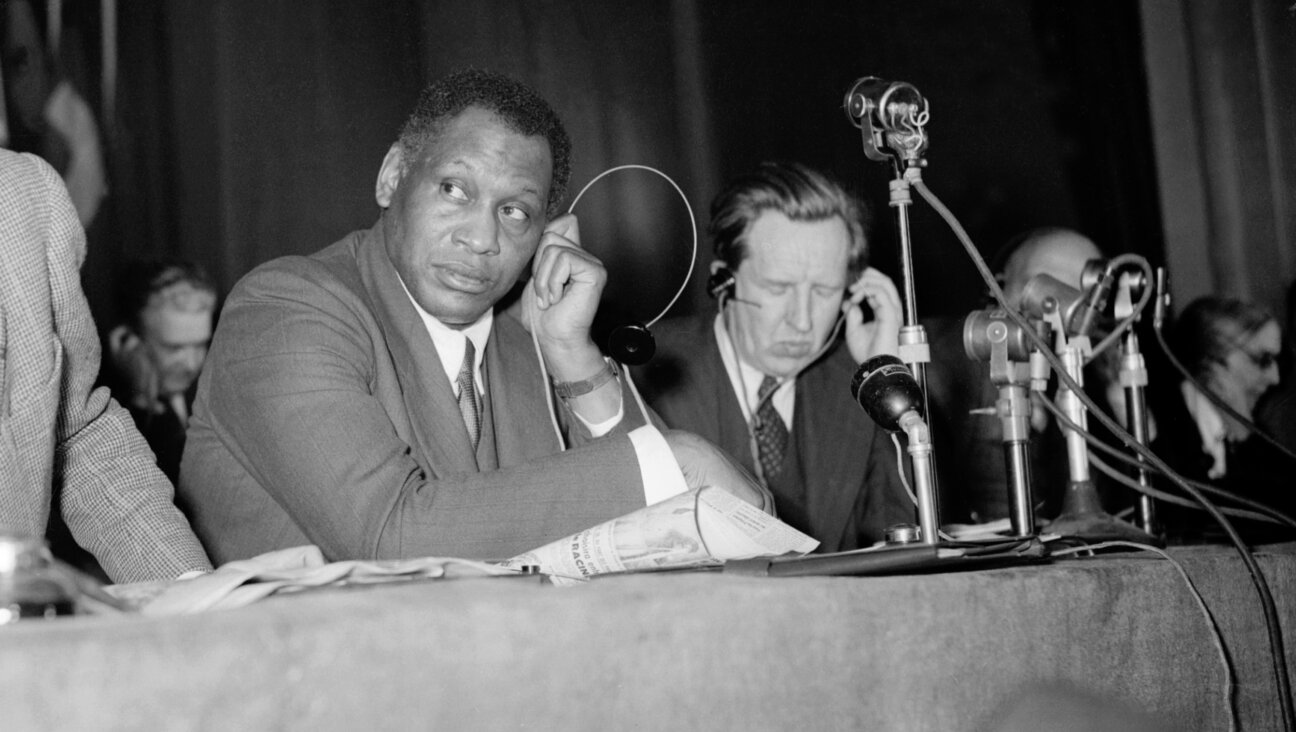

Gawenda was born in 1947 in a displaced persons camp in Austria to Holocaust survivor parents who had escaped the Nazis by fleeing to the Soviet Union. Before the war, his father was a poor weaver in Lodz, Poland and was a member of the Bund. In Melbourne, Michael/Moyshe grew up in its Yiddish-speaking secular leftist community, attending the Sholem Aleichem day school and spending summers at a Bundist sleepaway camp.

As a young man, he had little interest in exploring his Jewish identity or relationship to Israel, even though some of his family had moved to Israel in the late 1940s. Gawenda was not a Zionist, though he had no animosity towards Zionism or Zionists in his Bundist community. The Bundists believed in Yiddish and “Doikeyt,” the idea that Jews should be free to live as Jews anywhere in the world.

Today, writes Gawenda, the concept of Zionism is “freighted with new, dark meanings, and every diaspora Jew seems forced to choose which label fits best.” He makes an important point here, since Zionism was once the subject of internal debates solely among Jews. The Zionists believed that the Jewish state would solve Jewish problems, while their opponents had their doubts.

“We never debated whether Israel was or wasn’t a racist, colonialist state,” he writes. But now, even the right of the State of Israel to exist is in question, especially among leftist circles in Europe and America. Older Bundists and leftist Zionists now feel completely excluded from their leftist political “home” unless they agree that Zionism is a form of racism and colonialism.

Gawenda reexamines the worldview he grew up with as a Bundist in Melbourne. There, the Yiddish language was a means to instill humanist values in children. Their Yiddish was “universalist, secular, and left-wing.” This approach to the language was different from that of the classical Yiddish writers, which was deeply rooted in Jewish tradition and ritual, and was filled with Loshn-koydesh — religious terms derived from ancient Hebrew and Aramaic.

Gawenda observes that Yiddish has become popular among leftist Jewish activists, anti-Zionists and anti-racists. “Yiddish is ‘good’ because it isn’t a national language or the language of the powerful, and it’s a language that Zionists always associated with the diaspora and Jewish helplessness.” But in the last chapter of his book, he writes that he wants to “return to Yiddish,” read Yiddish books and maybe even the Tanakh (the Bible) in Yiddish. In essence, he wants to imbue his secular Jewish identity with a deeper Jewish content.

The old Bundist, Yiddishist approach to Jewish identity is no longer appropriate for these times, Gawenda writes. In his search for new approaches to Jewish identity, he read works by a diverse cross-section of Jewish writers and thinkers like Dara Horn, Howard Jacobson, Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem. He agrees with Dara Horn’s premise that “the world loves dead Jews,” because people are more likely to have compassion for innocent victims. But when it comes to living Jews, especially those that fight for their right to self-governance, the world doesn’t look kindly on them.

Like many Jewish intellectuals today, Gawenda feels forced to reconsider the very essence of his Jewish identity. Where should he stand on Israel and on anti-Zionism? What does Zionism mean today? Is it a national liberation movement or a form of colonialism? How close is anti-Zionism to antisemitism? These questions are dominating conversations among Jews everywhere. Gawenda’s autobiography can serve as a useful guide for these discussions.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO