My great-grandfather, a strike leader, paid dearly for his activism

In 1919, the Boston Globe published his letter protesting the way the police treated striking textile workers

Chaim “Ime” Mendl Kaplan in his cell at the Deer Island Prison, January 1920 Courtesy of the Kaplan family archives

Read this article in Yiddish.

I learned something unexpected about my great-grandfather this summer.

My husband, children and I had gone upstate to visit my grandfather’s first cousin Rebecca, in Woodstock, New York. A woman in her early 80s, she is one of the last surviving Kaplan women of her generation.

As soon as we walked into her one-story home, she handed me a book opened up to a page with my great-grandfather’s photo. He’s standing behind bars, wearing a dark vest and tie over a starched white button-down shirt. The year was 1920; the jail was Deer Island Prison in Boston Harbor.

As his son (my grandfather) explained to me years ago, my great-grandfather, known as Ime Kaplan because most people couldn’t pronounce his first name, Chaim, landed in jail. This wasn’t due to any criminal activity, but a result of his passionate political activism. Although I’d heard about him from relatives before, I didn’t realize until then just how influential he was. The Boston governor, and even the federal government, knew about him.

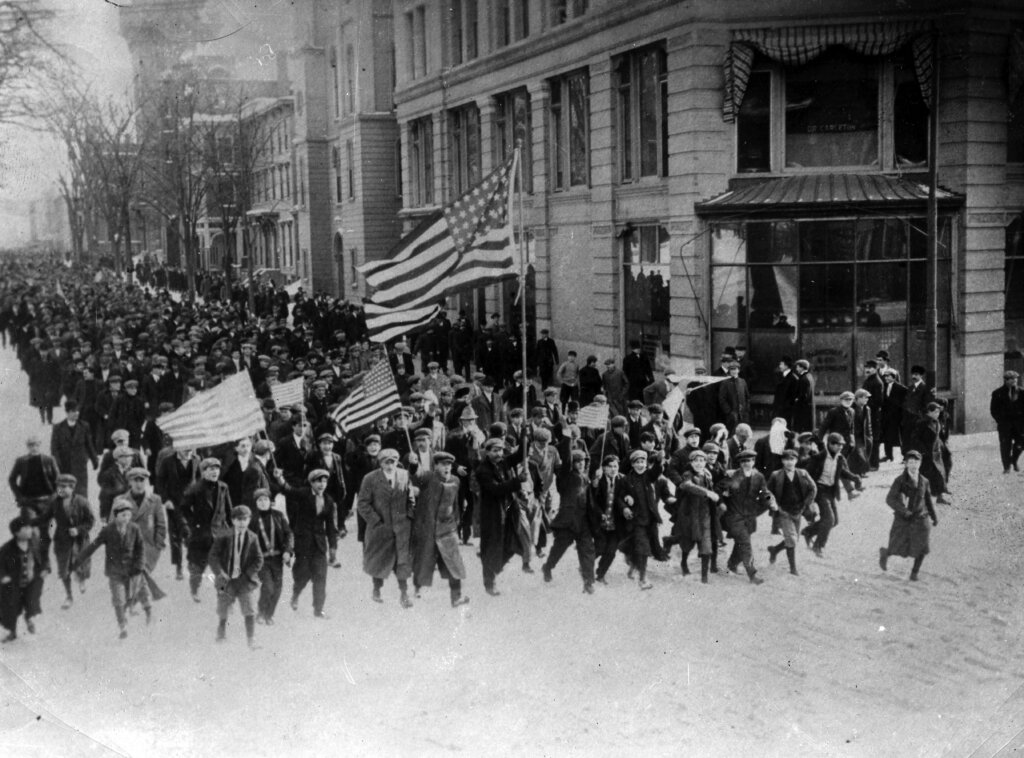

Beginning around 1910, Ime led strikes for immigrant textile workers, demanding an end to “starvation wages” and expressing the collective desire for the immigrant workers’ families to get an education. He was a charismatic social activist who dreamed of creating a better world. As my Uncle Don put it, “I suppose you’d call him a revolutionary.”

Unfortunately, my great-grandfather also suffered greatly for it.

I leafed through the book that Rebecca handed me, America’s Reign of Terror: World War I, the Red Scare, and the Palmer Raids. In it, the author, historian Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht, discusses the American government’s campaign to suppress dissent between 1917 and 1920. I soon discovered that Ime’s arrests were also reported in many newspaper articles at the time.

When I returned home, I searched Newspapers.com and was stunned to see his name printed under his photo on the front page of The Boston Globe, with the headline “Strike Leader Released.”

In fact, in 1919, the name Ime Kaplan appeared dozens of times in The Boston Globe, and more than once on the front page.

I grew up hearing stories about him from my grandfather Harry. “Honey, there wasn’t even a weekend then,” he once said. The five-day work week wasn’t instituted for factory workers until 1926, when Henry Ford announced it for his own workers. And the weekend didn’t become a legal guarantee for all U.S. workers until 1940.

Ime was born in 1893 in Vasilishki, a shtetl near the city of Minsk, in the Vilna Gubernia region of Eastern Europe, to Meyer and Tsipe Kaplan. He was sent to cheder, a traditional Hebrew school for boys, and was groomed to become a cantor. Sometime in the early 1900s, Ime’s parents and their children fled violent pogroms in Eastern Europe and arrived at Ellis Island.

At age 13 or 14, Ime became a worker in the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts, together with his parents and sisters. A Yiddish-speaking teenager, he taught himself English at night school. He met his wife, Lizzy, in the woolen mills. He must have had natural leadership qualities because, despite his lack of formal schooling in America, he quickly became the secretary of the General Strike Committee in Lawrence. In 1919, a letter he wrote in the name of striking textile workers, addressed to the Massachusetts governor, Calvin Coolidge, appeared in The Boston Globe.

Ime published the letter as the voice representing 20,000 “striking textile workers of Lawrence, in protest against the treatment that we have been receiving at the hands of the police authorities of our city.”

“We have seen the workers of Europe overthrow governments and secure rights and privileges never before attained,” he wrote. In 1917, near the end of World War I, a wave of workers and soldiers had indeed begun striking in Italy, Germany, and most notably, Russia. Governor Coolidge rejected the Strike Committee’s demands to unionize and to “parade peacefully.” Not until 1935 did Americans earn the right to legally unionize.

In January 1920, Ime was jailed for his leadership in the emergent labor movement. As part of the Palmer Raids, undercover federal agents arrested more than 6,000 activists across 36 cities they deemed “alien radicals.” He was labeled a Russian immigrant, a Jewish rabble rouser, a socialist and a Marxist. Other Jewish immigrant anarchists targeted in the Palmer Raids included Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

The Palmer Raids marked the beginning of the “First Red Scare” — the U.S. government’s deep fear of left-wing activists, including those in the labor movement. This red shadow would follow my grandfather’s family for another generation, into the McCarthy era.

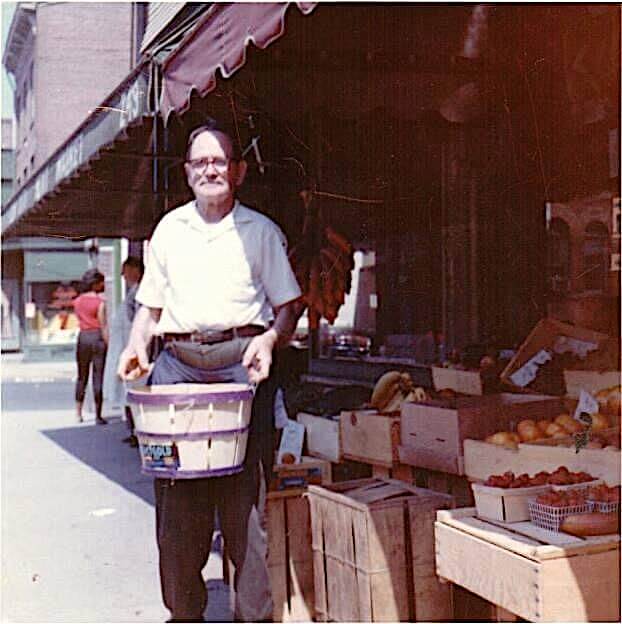

Ime’s legacy of activism haunted him his whole life. He was blacklisted “up and down the east coast,” according to my father, Bob, one of Ime’s oldest grandsons. Seeking a job, Ime and his family moved to Philadelphia. His brother, Rabbi Joseph Eli Kaplan, the spiritual leader of the Atlantic City Community Synagogue, helped him find work as a fruit and vegetable push-cart peddler. Years later, Ime’s oldest son (my grandfather) Harry told me about the horse that pulled the cart, and how his special job was to wash and brush that large animal that he loved like his own pet.

Ime settled in a community of Yiddish-speaking socialists in New Haven, Connecticut, along with his aging parents. He opened a fruit-and-vegetable shop on Legion Avenue. Like the Lower East Side, the small business district contained it all: the grocer, the butcher, the baker, the dry goods store. All shops were owned by Jewish and Italian immigrant families.

Every now and then, someone would try to rob the store. Even as an older shopkeeper in his 60s and 70s, Ime, unarmed, “could take the gun away from the burglar,” Uncle Don said. He usually emerged from the scuffle with a bloody face.

In the worn photos my Great Aunt Mildred (Ime’s youngest and only daughter) first showed me about 12 years ago, he’s standing by his shop with a grocers’ apron wrapped neatly around his waist. He’s smiling, a kind of closed-lipped, down-turned smile that looks like a frown. I’ve often seen my family members, first generation immigrants, make that kind of smile.

Ime lived a life of hardship: blacklisted, impoverished and evicted. His wife Lizzie and four children were tossed onto the curb countless times. Once he became a grandfather and a great-grandfather, his family life offered him some nakhes (joy).

All along, Lizzie, the “practical” one, counterbalanced his quixotic ideals. She managed the family’s meager finances, ensuring everyone would eat. “She even brought chicken soup to him in Deer Island prison,” my great-aunt Mildred, Ime’s youngest daughter, said. Ime may have been principled, but he loved his wife’s home cooking.

My great-aunt Mildred described Ime’s three sons (her older brothers) as tall, handsome young men “with movie star qualities.” But when the eldest son, Harry, got a full merit-based scholarship to Yale University, Ime didn’t congratulate him. Did his pure anti-capitalist principles keep him from praising his own children? Yet, Ime lived to see the birth of several great-grandchildren before his untimely death in 1973, the victim of a horrific hit-and-run collision, caused by an elderly, vision-impaired driver. Lizzy survived.

After reading the 1919 headlines to my 7-year-old son, I said, “Your great-great-grandfather Chaim Mendel was famous!” I told him how he was arrested while working to make the world a better place, during a time when there were no laws yet to protect the workers. “Oh, so he was kind of like Rosa Parks?” my son asked.

In a way, maybe he was. As a Ukrainian-Jewish immigrant activist, he risked arrest to challenge the unfair laws of the time.

“Did you learn about Rosa Parks from Xavier Riddle?” I asked him, referring to a PBS Kids show that teaches elementary school-age kids about history.

“Yes,” he answered. “Why can’t Chaim Mendl be on Xavier Riddle?”

It’s a great question. I’d like to know that, too.

Correction: An earlier version of this story implied an incorrect end date of World War I. It ended in 1918.