With ‘Tefila,’ David Broza blurs the line between prayer and performance

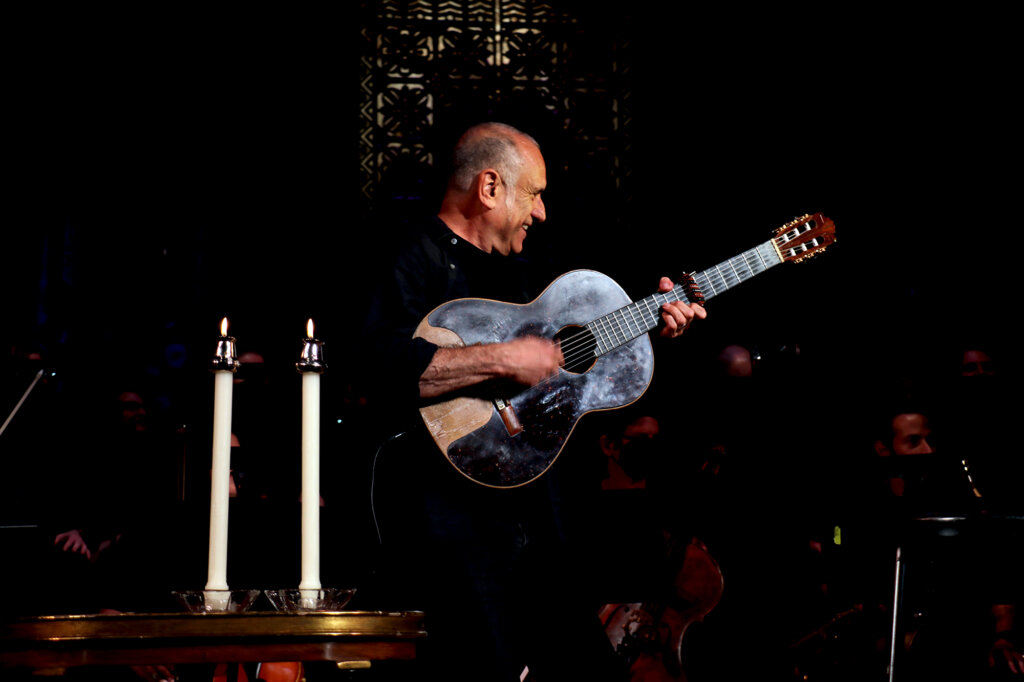

The Israeli singer-songwriter now leads Kabbalat Shabbat at Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

This is an adaptation of Looking Forward, a weekly email from our editor-in-chief sent on Friday afternoons. Sign up here to get the Forward’s free newsletters delivered to your inbox. Download and print our free magazine of stories to savor over Shabbat and Sunday.

Talking to David Broza about his latest project made me a little uncomfortable. Broza, an Israeli singer-songwriter whose style is often compared to Paul Simon or James Taylor, kept using words like “rehearsal” and “show” and “lyrics.”

But we were talking about tefila, prayer — or, rather, “Tefila,” Broza’s new album, a compendium of “tracks” from the Kabbalat Shabbat service Jews recite every Friday night, reimagined as a mix of bluesy jazz, pop, folk and classical tunes.

I have always been a bit allergic to prayer that smells like performance. I grew up in an Orthodox shul where davening was mostly lay-led and communal. My most connected Jewish moments came at summer camp and United Synagogue Youth conventions whose services were sing-a-longs.

In my adult wanderings through Conservative and Reform congregations, I have dismissed those where cantors seem to sing for rather than with the people in the pews as feeling too much like church.

Now here was Broza, a profoundly secular Jew who for years was a staple at City Winery, talking about the band he’d put together for the monthly First Fridays gig he’d booked at Temple Emanu-El Streicker Center in Manhattan.

“This was my first time reading these prayers, and thinking about them in a form of song, and not liturgy,” he said. “It doesn’t come with any weight of my father, my grandfather, my great-grandfather, 2,000 years of wandering, none of that. It’s now, and the Hebrew is magnificent. And those poets that wrote these prayers are as relevant as anybody today. And that’s magical.

“Shalom rav, al Yisroel — wow, I hear that in my heart,” Broza continued. “I don’t want to sound overdramatic, but it quivers. It really, really hits, like an Otis Redding song. It’s gospel, it’s deep. Because it also has a simplicity and yet the beauty within the language, like in L’cha dodi — you can go on interpreting, talking about it forever, because it’s so beautiful. It touches in so many directions. And it’s really celebrating the end of a week.”

I first met Broza a decade ago, when a friend dragged me to his annual concert at the foot of Masada for Tu B’av, a kind of Israeli Valentine’s Day. It was an insane experience: we caravanned from Jerusalem after midnight for a show that started around 3 a.m. Broza and his band rocked and rolled in the desert darkness for hours, culminating with his signature anthem, “Yihye Tov,” as the sun rose over the storied ancient fortress.

The husband and I were the only ones in the crowd who didn’t know every word — the only ones not singing each of those words along with Broza, just like we do with our cantors at Shabbat services. “Yihye Tov,” is, after all, a kind of prayer.

The title means, essentially, “all will be good,” and the lyrics, written by Yonatan Geffen in 1977 as Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat made a historic first visit to Israel, include “We will yet learn to live together… Children will live without fear…. One hundred years of war, but we have not lost hope.”

Not so different from the “Prayer for Peace” many American Jews recite each Shabbat in synagogue. When we spoke recently, I asked Broza — who has made more than 40 albums mixing Hebrew, Spanish and English, flamenco, folk, rock and jazz — whether he, himself, is praying in “Tefila.”

“Well, let’s analyze a prayer,” he began. “What is a prayer? You know, a prayer is, let me cross the street without getting run over. Let me meet the woman I will love for the rest of my life. I hope I’ll find a restaurant that I like tonight. Let me pass this test. Let me grow up and be healthy. These are all prayers, it doesn’t matter what language.”

When Gady Levy, the secular Israeli who runs programming for the Streicker Center, first asked Broza, back in April 2020, to consider rewriting the music for Kabbalat Shabbat to entice young people to come to shul, Broza demurred. “I said, look, I don’t know why me, I’m a secular Jew — I’m not Apikoros, but maybe close,” he recalled.

Over the next four months, Broza exhausted his pandemic bucket list — “I practiced what I wanted to practice, I learned the songs I wanted to learn, I wrote, I read books, everything one can do in quarantine,” he said. “But then the list was gone. I was done. My head was clear. My soul was completely like, OK, we’re at a standstill, nobody’s moving. And I remembered that email Gady Levy sent me, so I opened it up. And there I saw candle lighting.

“So I pull out my guitar. I want to see what’s gonna come out,” he continued. “And this thing, it literally came out in no time — baruch atah adonai… I’m hearing this melody with a bluesy feel to it.”

Over the next 14 days, Broza wrote 14 “songs” — new renditions of 14 prayers, all in different styles. He did not consult any cantors or listen to recordings of Kabbalat Shabbat. He said his main inspiration was actually the Misa Criolla, a Spanish-language version of the Catholic Mass he remembered from when he was 15 and living in Madrid, particularly a version by the Argentine folk singer Mercedes Sosa.

Broza, now 66, had rebelled against religion as a kid. He spent a year of high school at a London yeshiva, where he upset the rabbis by playing guitar on Shabbat. Like many secular Israeli Jews, he lights candles and makes kiddush most Friday nights but only sets foot in synagogue on the High Holidays.

“I’m the obstinate Israeli, fighting with my father about religion, even when I’m 8 and 9 and 10, why do I owe to anybody to follow his tradition?” Broza told me. “Now, as I’m sitting and I’m thinking about the concept of what I’m writing, and this is 2020, all this comes back to me. These are tools that I’ve actually received without being aware of it.

“And the respect that I have for the prayer, for the gathering, for the communing — the communal feel of writing a prayer, which is very similar to having rock ‘n’ roll concerts where everybody gathers and communes and sings together the words,” he continued. “There’s a similar thing about it. It’s like a shrine, you know?”

Music written, Broza, who splits his time between Tribeca and Tel Aviv, stopped by the Israeli-owned 1803 Bar in his New York neighborhood one day and was moved by the jazz being played by Omer Avital, an Israeli bassist. He asked Avital to join the project, and together they recruited 22 musicians and two choirs, one in Israel and one in New York, recording “Tefila” in a Brooklyn studio.

The album is free to download, and Broza will perform it live at Emannu-El on the first Friday of each month through January. At the debut last week, Levy said, 986 people were in the pews, most of them under age 40. Emanu-El is encouraging synagogues worldwide to incorporate “Tefila” into their own services.

And Broza has bigger plans. “I want to open maybe a year from now on a Friday night at St. Patrick’s Cathedral,” he said. Then maybe the Vatican, for the Pope. At Sultan’s Pool in Jerusalem. In Spain, where he spent part of his childhood, “the places where the Inquisition was — we still feel it in our blood, in our DNA.”

“Let’s think about this for a second: I heard a Christian prayer that inspired me to create, to me, the most meaningful Jewish prayer,” Broza said. “I think this Jewish prayer will be appreciated by Christians, by Muslims, by all.

“We own it because this is our Jewish thing, but it’s not ours to be owned, liturgy is always something that’s shared, we don’t know by who,” he said. “We survived all this time — our religion, our culture, our people, our language, survived all this time. This is what it sounds like now.”

Amen. And Shabbat Shalom.

Watch: Broza Live

Almost exactly two years ago, I hosted David Broza for a “concert and conversation” via Zoom. It was a cultural and spiritual highlight of those early months of pandemic lockdown, and still one of my favorite of the dozens of virtual events we’ve down over the last two years.

Your Weekend Reads

As the U.S. marks 1 million deaths from COVID-19, we remember 10 Jews — the number required for a quorum to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish — lost to the disease. Plus: Conservative rabbis defy ban on performing intermarriages; inside the last days of a small-town synagogue; and an investigation into the origins of pastrami.

“Where pastrami comes from matters,” writes Andrew Silverstein. “It’s beyond the pale to suggest that pastrami’s native habitat is white bread and barbecue sauce, not rye and mustard.” Download the printable (PDF) ➤