Inside the last days of a small-town synagogue

In East Texas, the eight members of Temple Emanu-El prepare for the end

All but one of the remaining congregants of Temple Emanu-El in Longview, Texas (from left to right): Natalie Rabicoff, Jeff Milstein, Laura Romine, Dr. Raul Zapata, Howard “Rusty” Milstein and Mendy Rabicoff Photo by Melanie Grizzel

In a quiet room of a once bustling Texas synagogue, Laura Romine sits alone, pulling dusty books off the library shelves. She carefully logs each title and author: “A Child’s History of Jewish Life” by Dorothy Zeligs, “Leo Rosten’s Treasury of Jewish Quotations,” Bernard Malamud’s “The Fixer.”

Romine, 60, has spent hours each week over the last six months going from room to room, logging 640 books and about as many other items: star-shaped Seder plates, oil paintings, a ping-pong table, guest books and, of course, Torahs. There are three holy scrolls that belong to Temple Emanu-El in Longview, Texas, and they, like everything else — including the large, mid-century synagogue building, dedicated in 1957 — have to go.

Romine is one of the last eight members of the synagogue, a Reform congregation which for decades was a hub of Jewish life in East Texas. She and the others are deep into the painful process of shutting the sanctuary doors for good.

“So many interesting people came through these doors,” she told me during a recent visit. “People with so much intelligence and people who contributed to the community. I don’t want people like that forgotten.”

“There are so few of us now,” she added. “It’s not just a place of worship. It’s truly like a family.”

Once-flourishing synagogues like Temple Emanu-El are casualties of the social and demographic shifts in American Jewish life; a 2020 Pew Research study showed that though some three-quarters of the Jewish American community considers Jewishness important, only 1 in 5 Jews attend synagogue monthly.

There are currently 796 Reform synagogues in the United States, down from 976 in 2001, according to research provided by Prof. Ira M. Sheskin, an editor of the American Jewish Year Book. That’s an 18% drop. In the same period, the number of Conservative congregations shrunk 36%, to 548, and Reconstructionist synagogues declined 10% to 89.

(It is difficult to track Orthodox synagogues, given they include many small neighborhood shteiblach, but research shows that segment of the community is growing and remains active in synagogue life.)

Like Emanu-El in Longview, many synagogues become a second home to their congregants, who grow to be like family. But what happens to the building, its belongings, and the families that grew up there when the home shuts down for good? I drove the four hours from my home near Austin to Longview to find out.

My grandfather, a first-generation Russian Jew, was born about 90 miles north of Longview, in the city of Texarkana. The history of Jews in Texas is a subject that’s close to my heart, and I knew that the members of Emanu-El had stories to tell. Stories of weddings and funerals, bar mitzvahs, Purim carnivals and Passover Seders. Tales about the Food-o-Rama fundraisers where the whole town turned out to try Jan Statman’s Herring Salad or Yehudit Barzel’s Dairy Kreplach. Stories that, if they weren’t passed on soon, could be lost to future generations forever.

The temple is situated in the center of a residential neighborhood, surrounded by the towering loblolly pine trees so common in that part of the state. From the front, the beige-brick building has a large center entrance rising above shorter wings on either side, a Texas-size menorah.

A historic marker out front lets visitors know that the oil boom of the 1900s lured many Jewish families to the area, and that Emanu-El has its origins down the road in Kilgore’s Beth Shalom, which was consecrated in the 1930s and closed in 1979.

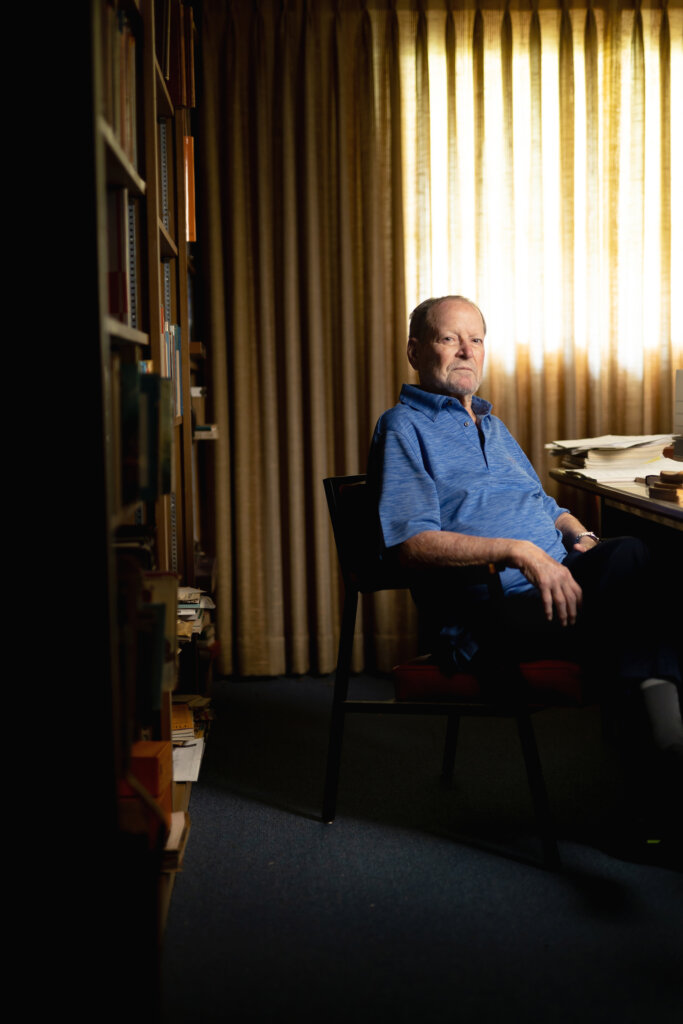

When I drove up to the temple on a chilly Friday evening in February, I met Romine in the parking lot, and then walked inside through a dimly lit hallway, past the kitchen, and into the quiet sanctuary, where Rusty Milstein, 77, a retired vice president of a steel warehouse, and his son Jeff were standing alone in a room that once held 180 people.

Milstein had warned me via email that the HVAC in the social hall, where the classrooms, offices and library are located, was broken. Though February is cold in Texas, they had no plans to fix it; too few people entered those rooms these days, and eventually, the heat would be turned off for good anyway.

Sunday School ghosts

Milstein had opened the sanctuary doors the day before to let the heat from that part of the building flow through, which helped. He and his son led me down a hallway with faded paper-doll cutouts and children’s drawings taped to the doors. The rooms were exactly as they stood the day Sunday school classes ended due to lack of enrollment 20 years before.

Emanu-El’s Sunday school had always been taught by parents and volunteers, not formal educators. So local families had, over the years, taken to sending their children instead to Tyler, a city of more than 100,000 residents that’s about 40 miles southwest of Longview. Tyler’s synagogue, Beth El, has a full-time rabbi; Emanu-El has lacked one since 2005, instead having visiting rabbis come for High Holidays or Passover.

We stepped inside one of the classrooms, where a ping-pong table and paddles sat idle in a corner. Crayons and drawings were strewn about.

“It’s like a ghost town in an old Western,” said Milstein, chairman of the temple’s building and grounds committee. “The last kids who were here are in their 30s now.”

Jeff Milstein, who is 53 and owns a local bar, spent much of his childhood in these rooms. “I’m the youngest member and my beard is white,” he said. “The kids have grown up and moved away, and nobody has replaced them.”

The library down the hall also looked as if time had just stopped one day. There were books left open on a large wooden table in the center of the small room. Romine is in charge of cataloging them all — they will be donated to libraries and schools — as well as the ritual items. Who will get the eternal light, or the Tree of Life wall whose gold leaves commemorate past events? Many of those leaves are blank, a sign of the synagogue’s slowdown.

Then there’s the gorgeous ark, with its stained-glass doors, in the center of the sanctuary. It was donated to Emanu-El by Anshe Emeth synagogue in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, which itself closed in 2016 after nearly 150 years.

‘You run out of people’

In the Pew Research Forum’s 2020 study, 20% of American Jews said they attend synagogue at least once a month, down from 26% in 2000. The overall number of people identifying as Jewish in the United States has increased since 2013 from 6.7 million to 7.5 million, and the Jewish population in Texas has grown, too, from 130,000 in 2010 to an estimated 176,000 in 2020. But while the Jewish population in Austin has quintupled in the last 30 years amid that city’s overall growth in the tech boom, in smaller cities and towns like Longview, it’s becoming harder to fill up the seats.

The town’s Jewish population peaked in the post-war years, when the oil business attracted retailers, attorneys and doctors to the area. By the mid-1970s, members had to bring extra chairs into the sanctuary to handle the demand for seating. The youth group had 30 members.

But most of those young people moved away for college or jobs. Those who remained have other priorities.

“In a town the size of Longview, football is the Friday night thing,” Milstein said. “It’s hard to dissuade kids from going to a football game to come to services.”

Romine and Milstein said they had been talking about the inevitable closure of Emanu-El for a few years. When Milstein was a kid, there were about 60 families. Thirty years ago, there were about 15. Now, it’s just the eight of them. They officially decided last September to start the process.

“Plans needed to be made,” Romine explained, “because none of us were getting younger.”

One of their first steps was to contact Noah Levine, senior vice president of the Jewish Community Legacy Project. Based in Atlanta, the group helps small congregations in the U.S. and Canada “secure their futures,” according to its pamphlet. That translates to walking congregants through the many decisions involved in closing a synagogue, including what to do with any remaining funds or other assets. Levine said that any remaining funds from the sale of Emanu-El will be converted into endowments (or one-time donations) and will be used for Jewish camps for Texas children. They will also be donated to a local social welfare agency in Longview.

Since 2010, the group has helped 28 synagogues close, Levine said. Eighteen others have completed legacy plans for eventual closure or merger, he added, and another 106 have contacted the group about potential shutdown.

“For many small town congregations,” he said, “demographics are not in their favor. The process is emotional and it’s rational, and we help balance that.”

At Temple Emanu-El, Levine helps the members stay on track by checking in to make sure appraisals have been completed, inventory is moving forward, and that the legacy of the synagogue will be preserved by donating items to organizations that will display or use them, instead of putting them in boxes, where future generations may never discover them.

The last eight members of Emanu-El know it like their own homes, and as we walked through the building, they shared details about every painting, photograph or artifact on its walls. There was a black and white photo of the construction of the temple, and Milstein said that the circular drive was built by prisoners from the Gregg County jail. A series of color photos lining the hallways showed past members dressed in their 1960s finest — pastel A-line dresses, crisp suits and ties. That was back when the Sunday school classes were full, and weekends were bustling with bar mitzvahs, weddings and Purim carnivals.

Milstein made it clear that Emanu-El was not shutting down for financial reasons. The temple paid off the building some 40 years ago, he said, and has no full-time paid staff. But there are just no longer enough people coming to services or ready to sustain the congregation.

“For the most part, you don’t run out of money,” said Levine, who has seen this story many times before. “You run out of people.”

Nicknames and Jewish journeys

Back in the warmth of the sanctuary, Tami Stewart, who has worked part-time at Emanu-El for about 15 years, set several round tables with a Texas Shabbat feast: challah, fried chicken, BBQ brisket and beans. Bottles of hand sanitizer served as centerpieces. Dr. Raul Zapata, a semi-retired physician, walked in wearing denim overalls and holding a wooden cane, hand-carved with Peruvian symbols.

“That’s Dr. Zapata,” whispered Natalie Rabicoff, 78. “He brings the wine.”

Milstein calls Zapata “Coach” and Romine “Scooter.” They call him “Bossman.” They’re a tight unit, full of inside jokes that come from years of friendship.

Rabicoff recalled their days volunteering at the local police station on Christmas, answering the phones or taking care of the station so the employees could have their holiday off. “We were like little elves,” she said.

Rabicoff grew up in Houston, and going to temple there was more about dressing in your finest and looking your best, unlike Emanu-El, a place she said was always “delicious and fun.”

Romine grew up Southern Baptist, but it “never felt right,” she said. A friend of her sister’s had a book about Judaism, and when Romine read it, she said to herself, “These people think like me.” She eventually got confirmed and quickly became, as Milstein said, the backbone of the synagogue.

“It felt like I was coming home,” she said of joining Emanu-El some 20 years ago. To the others, she said, “Y’all had no idea when I walked in that door how much trouble I’d be.”

Before dinner, Milstein and Barbara McClellan, an 83-year-old food columnist for the Longview News-Journal, had headed to the front of the room to lead the prayers, in Hebrew and English. Later, McClellan told me she does her best to read Hebrew, but “the lack of vowels really throws you. To say I’ve learned Hebrew would be using that word very loosely,” she said.

During the meal, I asked Zapata how he became the designated wine guy. Turns out he once owned a winery. Zapata grew up in Piura, Peru, where his Jewish heritage was largely kept a secret – his father would sneak away on Fridays and during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Once, during World War II, his father took him and his oldest sister to a seaport in northern Peru where, Zapata recalled, there was “a big old ship full of people yelling.” It was a ship full of Jewish immigrants fleeing Europe. “Aren’t we lucky?” Zapata remembers his father saying about their relative security, compared to the passengers on that ship. He said he thinks of that day often.

It wasn’t until years later, though, when his brother, Nestor, called Zapata from his death bed in California, that Judaism became part of his everyday life. “‘Promise me,’” Zapata recalled his brother saying, “‘you will know who you are and go to synagogue.’”

This was around 2009. Zapata still works and lives in Kilgore, a town about a 20-minute drive from Longview. Over a decade ago, he heeded his brother’s last wish and made his way to Emanu-El, where, he said, Milstein and the others welcomed him with open arms. When I asked what his father would have said about this, he did not hesitate: “He would have said, ‘I’m glad you’re back to what you are.’”

McClellan, too, was not raised Jewish. She grew up in nearby Tyler, and remembers trading lunches with a girl in school who kept kosher. She always loved theater, and when she first played Golda Meir in a community production in 1975, when she was in her late 30s, she felt connected to the character and consulted with close friends who were members of Emanu-El, asking questions that helped her learn more about the character and the religion. The second time she played Golda, in 1982, she attended temple a few times, but not regularly.

After her first husband died in 1994, McClellan said Friday nights became a “horrible, lonely void.” She called her friend Jan Statman, a visual artist, and asked if she might accompany her to Shabbat services.

“Jan said, ‘Sure, come on in, Golda,’” McClellan recalled.

McClellan already knew Milstein because they’d acted in a production of “Fiddler on the Roof” at the Longview Community Theater together, and she quickly connected with others. By 2018, after the deadly shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, she was leading the “Mi Shebeyrach” prayer at the local memorial service. When she hears the kaddish, McClellan said, it’s like she’s “going back in time” to ancient traditions. It reminds her that people have worshiped this way for thousands of years, “despite the threat of death,” she said. “It transfers to my soul.”

The end

The morning after our Shabbat dinner, several members met with Levine, from the Legacy Project, to go over some logistics. The warmth and joviality from the dinner was replaced with a more somber tone.

They gave Levine an update on the building survey and appraisal: 5.92 acres, with a land and building value set at $700,000.

The members discussed what might become of the building and grounds. It could be transformed into a church. Or a developer might bulldoze it and build some homes. One person suggested donating the property and the building to the city, to become a park and community center.

“Putting emotion aside, when would you like the building sold?” Levine asked.

Mendy Rabicoff, Natalie’s husband, broke the heavy silence with a sigh, like the sound of someone grieving. “That’s a tough question, Noah,” he said.

Milstein said he did not want a “For Sale” sign out front. “It’s a sign of what’s coming,” he said.

Milstein then shared an email from Audrey Kariel, a longtime East Texas civic leader and historian who was once mayor of the small town of Marshall, about 20 minutes east of Longview. Kariel collects Judaica from around the state for the Harrison County Historical Museum, and she sent a list of things she’d like to add from Emanu-El.

“Audrey wants the lectern and a pencil drawing,” Milstein said. Then he paused: the list also included one of the temple’s Torahs.

Levine balked. “I don’t give opinions because I’m objective,” he said, “but a Torah should not be in a museum.” The members agreed: the Torahs should be donated to temples or organizations that would ensure they would remain in use, and not gather dust in a museum.

A few days later, the group voted to put up that For Sale sign. Milstein said the first time he saw it when driving by the temple, it made his stomach turn.

‘We were here’

The group plans to keep meeting at Emanu-El until the building sells. They know that, soon enough, the doors at 1205 Eden Drive will close for good, as the doors have at many small town synagogues across the country.

The lights will shut off, the ark and eternal light, the ner tamid, will be moved, and the eight remaining members will find another place to meet. Maybe at a community hall, or someone’s home. I asked McClellan what she wants people to know about this place.

“I want them to know that we were carrying on the traditions of people who died for these things for thousands of years, with the music and the rituals and the prayers,” she said. “I want that to live on.”

When I asked Zapata this same question, he simply said, “I want people to know that we were here.”

Correction: The original version of this article misstated some population figures. The number of people in the United States identifying as Jewish was 6.7 million in 2013 (not 5.3 million) and 7.5 million in 2020 (not 5.8 million), and the number in Texas was 130,000 in 2010 (not 150,000).